Background/Objectives: Cancer patients often experience psychological distress, and about 30% experience significant distress. A posttreatment educational intervention may help reduce the psychological distress level for this population. The purpose of this project was to determine whether the implementation of a nurse-driven psycho-oncological educational session would decrease psychological distress levels among patients with solid tumor cancers who have received and completed chemotherapy with curative intent.

Methods: Twenty-eight patients diagnosed with solid tumor cancers who received and completed chemotherapy with curative intent were recruited in an outpatient oncology center of a community hospital in Washington, DC. Participants were randomly assigned to an intervention group or to a comparison group. The intervention group received standard care plus an intervention consisting of 1 60-minute session of psycho-oncological education. The standard care group received information addressing an overview of the treatment process, side effects of the intervention, and identification of additional resources. Psychological stress levels of participants were assessed at baseline and 2 weeks after the intervention using the Distress Thermometer, which measures psychological stress on a 0-to-10 scale.

Results: Baseline psychological distress levels were higher in the intervention group than in the standard care group (mean [SD] = 5.86 [2.21] vs 4.07 [2.24]; P <.001). Psychological distress levels declined in the intervention group that received standard therapy plus psycho-oncological education (mean [SD] = 3.36 [1.69]) but increased in the group receiving only standard treatment (mean [SD] = 5.07 [2.76]; P = .029).

Discussion/Conclusion: Brief, nurse-administered psycho-oncological education may reduce psychological distress and may be a beneficial adjunctive treatment to reduce stress among patients with solid tumor cancers who received and completed chemotherapy with curative intent. Future research is needed with larger samples to validate the findings of this project among similar patient populations.

Despite the advances in survival arising from early detection, increased treatment effectiveness and improved symptom management, cancer patients remain vulnerable to psychological distress. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) reports that, although some level of stress is normal, about one-third of all cancer patients experience significant psychological distress.1 The NCCN further reports that as many as 19% of cancer survivors experience symptoms that meet the criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder.2 “With an estimated 1,665,340 Americans being diagnosed with cancer in 2014,”3 based on the NCCN estimate, between 300,000 and 500,000 cancer patients will experience significant psychological distress each year.

Elevated levels of psychological distress have been linked with reduced health-related quality of life (QOL).4 Psychologically distressed persons seek more medical services, have more difficulty making decisions, are less adherent to their treatment regimens, and are less satisfied with their medical care.5 Cancer survivors with untreated distress are also at higher risk for late adverse outcomes due to psychosocial risk factors.6 Reducing psychological stress associated with cancer treatment is a large unmet need.

Patients with solid tumor cancers who have completed chemotherapy with curative intent experience psychological distress. As a result, these patients experience poorer QOL, emotional vulnerability, and unnecessary emotional suffering. Regardless of where patients are on the illness trajectory (newly diagnosed, treatment phase, posttreatment phase, or survivorship), they are in need of receiving transition care to include psycho-oncological education. Some patients may feel that a lack of information about cancer survivorship increases stress, as illustrated by the following statements from a patient in one author’s home institution:

“I didn’t have a lot of information provided to me, and I felt that there was a communication gap. I felt lost, which added to my stress. I was unable to anticipate how the various areas of my life would be impacted. For me, what has been worse than cancer has been not knowing what’s going on” (personal communication, 2015).

To serve patients with significant distress, oncology treatment teams will need to implement psychological distress management interventions to reduce psychological distress. Psycho-oncological education is one intervention that may help to reduce psychological distress among cancer survivors. Although educational interventions are less widely studied than more popular interventions such as mindfulness-based stress reduction, some forms of education are central to nearly all cancer survivorship programs. One study reported that stress was reduced in caregivers who participated in 3 1-hour problem-solving educational sessions,7 and another study reported that individual education sessions reduced pain among cancer outpatients.8 No studies, however, were located that measured the impact on psychological stress levels of educational intervention. Therefore, we conducted a randomized controlled trial to assess whether the implementation of a nurse-driven, psycho-oncological educational session decreases psychological distress levels among patients with solid tumor cancers who have received and completed chemotherapy with curative intent.

Methods

This randomized pre-post intervention pilot trial was conducted in the oncology ambulatory center at a 300-bed community hospital in Washington, DC, after receiving approval from the institutional review board. Eligible participants were either male or female, ≥18 years of age, non–race-specific patients with solid tumor cancers who received and completed chemotherapy with curative intent. Additional eligibility criteria included 1) no previous diagnosis of cancer prior to the cancer for which they were currently being treated, 2) a baseline NCCN Distress Thermometer (DT) score of ≤7, and 3) no diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder.

Approximately 30 patients were approached in the outpatient oncology center between May and September 2015 and screened for eligibility. Of those, 93% were eligible and expressed interest in participating in the study. Once patients met the eligibility criteria, and researchers obtained informed consent, patients were randomized to the treatment or control group using an online random number generation tool. Whereas the intervention group received 1 psycho-oncological educational session lasting 60 minutes followed by standard care, the comparison group received standard care only.

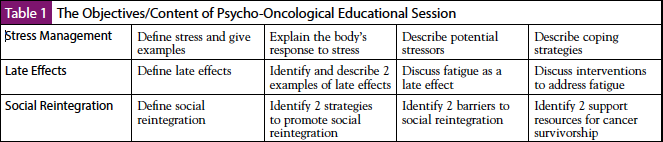

The psycho-oncological educational intervention included 60 minutes of face-to-face education on stress management and late effects of cancer, including fatigue, emotional difficulties, and social reintegration. The educational content was developed based on evidence published by the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the NCCN clinical practice guidelines for survivorship (Table 1). Each educational session was planned to be 60 minutes. Delivery of the education was individualized, and time spent on each topic within the session varied based on individual patients’ knowledge and contribution to the education. A question-answer period was provided at the end of the session. The face-to-face, individualized educational delivery method allowed for the participants to request the educational delivery in their preferred method. All participants in the intervention group agreed to receive the education through discussion and through the question-answer methodology. Standard care included a meeting with the nurse practitioner, who completed a symptom checklist and identified additional resources such as a nutritionist, a social worker, pastoral care, and palliative care.

The theoretical framework used in this project is Roy’s Adaptation Model, which presents the person as a holistic, adaptive system in constant interaction with internal and external environments with the goal of nursing to foster adaptation. Major concepts within this theory include adaptation, person, environment, health, and nursing. Adaptation is the primary concept of interest in this model; it is the dynamic process whereby people use conscious awareness and choice to create human and environmental integration.9 With the intent to initiate a successful coping process that leads to adaptation, a psycho-oncological program was implemented. The goal of the intervention was to eliminate or reduce psychological distress and improve QOL among patients with solid tumor cancers, hence promoting adaptation to the environment.

Participants completed the NCCN self-report DT prior to and 2 weeks after receiving the intervention or standard of care. The DT allows patients to rate their distress from 0 (no distress) to 10 (extreme distress). The DT is a valid tool to detect cancer-specific distress, and it has been found to perform well in a range of languages and across a number of cancer types, especially when using a cutoff ≥4.10 Data of Receiver Operating Characteristic indicates that a DT cutoff score of 4 yielded area under the curve (AUC) of 0.80 with an optimal sensitivity (0.80) and specificity (0.70) relative to the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and AUC of 0.83 with the greatest sensitivity (0.87) and specificity (0.72) against Symptoms Checklist 90.11 These researchers further note that the DT has acceptable test-retest reliability (r = 0.800; P <.001). Hence, the DT has acceptable overall accuracy and reliability as a screening tool for testing distress severity and specific problems causing distress in cancer patients.

Statistical Analysis

We hypothesized that the intervention group would experience a 2-point decline in the DT score from pretest to posttest, whereas the control group would have no change. We used a change score t test and assumed moderate correlation between pretest and posttest (R2 = 0.50) and minimal selection bias (Rxg = 0.10). Using power analysis in SAS 9.3, and an alpha of .05,12 we calculated that 14 patients were needed in each group to detect this 2-point decline with 80% power. To test the hypotheses, t tests and stepwise multiple regression were used. A paired t test was used to compare the within-group differences, and an independent t test was used to compare between-group differences.

Results

Patient Characteristics

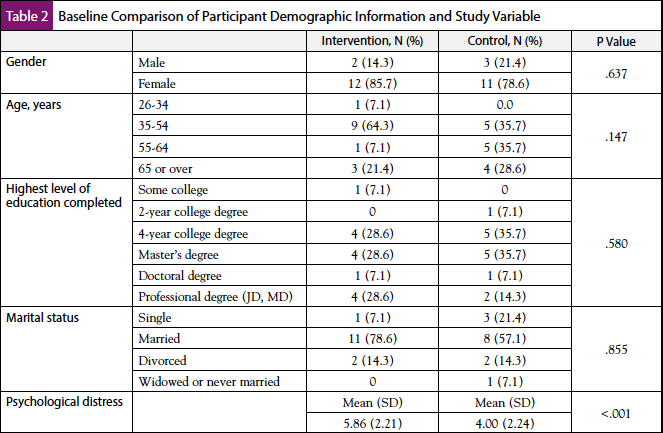

Baseline demographic data were compared between the intervention and control groups (Table 2). Among the 14 patients with solid tumor cancers in the intervention group, the majority (12, 85.7%) were females. More than half of the 14 patients were aged 35 to 54 years, and 3 (21.4%) patients were ≥65 years old. Four (28.6%) patients completed a 4-year college degree, 4 (28.6%) completed a master’s degree, and 4 (28.6%) completed a professional degree (JD, MD). The majority (11, 78.6%) of the 14 patients were married.

Among the 14 patients with solid tumor cancers in the control group, the majority (11, 78.6%) were also females. Five (35.7%) of the 14 patients were aged 35 to 54 years, 5 (35.7%) were aged 55 to 64 years, and 4 (28.6%) were ≥65 years old. Five (35.7%) patients completed a 4-year college degree, and 5 (35.7%) completed a master’s degree. More than half (8, 57.1%) of the 14 patients were married. There were no significant baseline demographic differences between groups.

Baseline comparison of psychological distress showed that the pretest mean (M) and SD scores (M [SD] = 5.86 [2.21]) were higher in the intervention group than the pretest scores (M [SD] = 4.00 [2.24]) in the control group (P ≤.001). This means that at baseline the participants in the intervention group experienced more psychological distress than patients in the control group prior to the intervention.

Distress Thermometer Score Changes

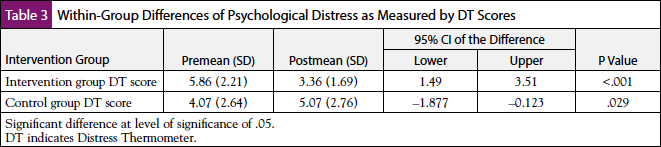

For both groups, the DT scores changed significantly between baseline and posttreatment. As seen in Table 3, for patients in the group receiving psycho-oncological education, DT scores dropped from a mean of 5.86 to a mean of 3.36 (P ≤.001), whereas for patients in the standard care group, the DT scores increased from a mean of 4.07 to a mean of 5.07 (P = .029).

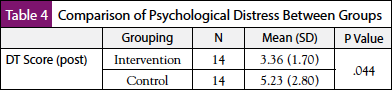

The results of the independent t-test analysis showed that the difference of posttest scores of the psychological distress levels was significantly lower in the intervention group (M [SD] = 3.36 [1.70]) compared with the control group (M [SD] = 5.23 [2.80]; P = .044) (Table 4). Specifically, the posttest mean in the intervention group was significantly lower, by 1.88, than the posttest mean of the psychological distress levels in the control group. This means that the psychological distress levels of the patients with solid tumor cancers were significantly decreased after the 60-minute session of psycho-oncological education compared with those who received standard care only.

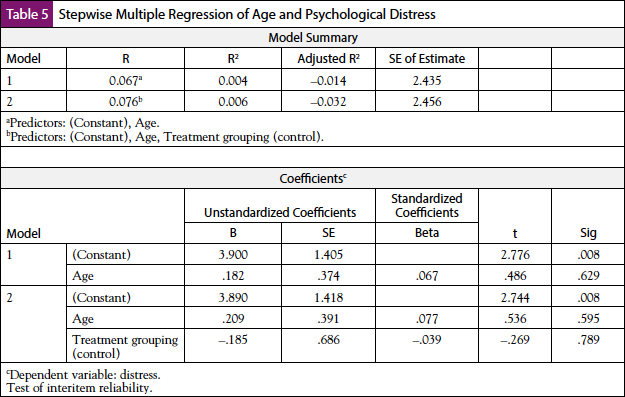

Because the between-group differences were significant, we performed a stepwise multiple regression to determine whether age and treatment group predicted the psychological distress level of patients with solid tumor cancers who received and completed chemotherapy with curative intent (Table 5). Age was entered in the first step, and age and treatment group were added in the second step. The results did not show a significant effect (P = .789). This means that the psycho-oncological educational intervention did not predict psychological distress levels.

Discussion

Our pilot quality improvement project showed that psychological distress lessened among patients in the intervention group compared with patients in the control group. Psychological distress levels, measured by DT scores, of the patients with solid tumor cancers were significantly decreased after the 60-minute session of psycho-oncological educational intervention compared with those who received standard care only. These findings suggest that the implementation of a nurse-driven, psycho-oncological educational session decreases psychological distress levels among patients with solid tumor cancers who have received and completed chemotherapy with curative intent. However, it should be noted that although the results of the stepwise multiple regression suggest that the intervention did not predict levels of psychological distress, we were not powered on this statistical test and therefore may have been underpowered to detect an effect.

What is interesting here is that regardless of where a patient was on the illness trajectory (newly diagnosed, treatment phase, posttreatment phase, or survivorship), psycho-oncological education was a successful intervention for lowering distress levels. The findings from this project, as they relate to psychological distress, paralleled the findings from many other studies in which the psycho-oncological educational intervention reduced distress levels as a result of offering education to cancer patients.11,13-18

Our finding that implementing the nurse-driven psycho-oncological educational session resulted in a statistically significant difference in mean scores with a favorable decrease in distress levels supports Roy’s Adaptation Model, which was the framework used for this study. By reducing distress levels, patients are better able to cope and adapt to stressors. The psycho-oncological education serves as an intervention to help expand each individual’s ability to enhance or influence adaptation, thereby enhancing personal transformation.

Establishing a standard for psychological distress screening and management at the organizational level includes the following benefits: 1) meets accreditation standards established by the American College of Surgeons to ensure quality, multidisciplinary, and comprehensive cancer care delivery in healthcare settings; 2) provides consistent and early recognition and detection of distress; 3) offers an opportunity to implement early, appropriate evidence-based interventions; 4) enables patients to experience decreased psychological distress and improved QOL as a result of the educational intervention; 5) may decrease cancer care cost to the organization and patient relative to psychological and physiological symptoms resulting from distress; 6) may better position the organization for seeking accreditation; and 7) follows national recommendations from the Institute of Medicine and the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology.

The findings of this project may help hospitals achieve cost savings associated with the need for fewer medical services associated with unmanaged distress, and this may improve overall patient satisfaction. As mentioned earlier, psychologically distressed persons seek more medical services, have more difficulty making decisions, are less adherent to their treatment regimens, and are less satisfied with their medical care.5 Cancer survivors with untreated distress are also at higher risk for late adverse outcomes due to psychosocial risk factors.6 The results presented here will lay the foundation for a larger-scale implementation of a psycho-oncological educational intervention. Training nurses to deliver the psycho-oncological intervention as a standard could enhance patient outcomes.

Strengths and Limitations

Because this quality improvement pilot excludes patients with diagnosed psychiatric disorders and patients with lymphoma and leukemia, the results cannot be generalized to these populations. Another limitation of this study is that patients may have received other therapeutic interventions unknown to the investigator. These additional treatments may have acted as confounding variables and influenced the treatment outcomes. Randomization, however, was used to balance the effects of these confounding variables between the treatment and control groups. Further implications for practice include determining the optimal timing to deliver this intervention and investigating further how long the effects of the intervention will last. Finally, because we powered our sample for a t test, we may have been underpowered to detect an effect in the multiple regression analysis of psychological distress. The strength of this study is providing data that support the value of psycho-oncological education and its positive impact on psychological distress for patients at this hospital. Furthermore, it supports the utility of psycho-oncological educational interventions to reduce psychological distress in this patient population.

Conclusion

This nurse-driven evidence-based education is a first step to reducing psychological distress among patients with solid tumor cancers. This quality improvement project has provided pilot data for planning a larger study of nurse-provided psycho-oncological educational programs that could be integrated into survivorship programs and fill a recognized need for these patients in hospitals throughout the United States. Recommendations from the NCCN guidelines for distress management advise treating patients at times of vulnerability, especially treatment termination.1 Finally, at the beginning of 2015, the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer required providers to treat patients for distress to meet accreditation standards. This study may help to achieve and further these recommendations and requirements.

Participating Investigators and Acknowledgments

Karen Smith, MD; Bruce Kressel, MD; Katherine Thornton, MD; Catherine Bishop, DNP. NIH P30 CA006973 awarded to the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins.

References

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Managing Stress and Distress. Version 1.2003. www.nccn.org/patients/resources/life_with_cancer/distress.aspx00/jco.2012.48.3040.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Survivorship. Version 2.2015. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#supportive.

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures 2014. www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsstatistics/cancerfactsfigures2014/index. 2014.

- Shim EJ, Shin YW, Jeon HJ, et al. Distress and its correlates in Korean cancer patients: pilot use of the distress thermometer and the problem list. Psychooncology. 2008;17:548-555.

- Holland J. Preliminary guidelines for the treatment of distress. Oncology (Williston Park). 1997;11:109-114.

- Carmack CL, Basen-Engquist K, Gritz ER. Survivors at higher risk for adverse late outcomes due to psychosocial and behavioral risk factors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:2068-2077.

- Bevans M, Wehrlen L, Castro K, et al. A problem-solving education intervention in caregivers and patients during allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Health Psychol. 2014;19:602-617.

- Oliver JW, Kravitz RL, Kaplan SH, et al. Individualized patient education and coaching to improve pain control among cancer outpatients. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2206-2212.

- Rogers C, Keller C. Roy’s Adaptation Model to promote physical activity among sedentary older adults. Geriatr Nurs. 2009;30(suppl):21-26.

- Chambers SK, Zajdlewicz L, Youlden DR, et al. The validity of the distress thermometer in prostate cancer populations. Psychooncology. 2014;23:195-203.

- Tang LL, Zhang YN, Pang Y, et al. Validation and reliability of distress thermometer in Chinese cancer patients. Chin J Cancer Res. 2011;23:54-58.

- Oakes JM, Feldman HA. Statistical power for nonequivalent pretest-posttest designs. The impact of change-score versus ANCOVA models. Eval Rev. 2001;25:3-28.

- Dolbeault S, Cayrou S, Brédart A, et al. The effectiveness of a psycho-educational group after early-stage breast cancer treatment: results of a randomized French study. Psychooncology. 2009;18:647-656.

- Ashing K, Rosales M. A telephonic-based trial to reduce depressive symptoms among Latina breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2014;23:507-515.

- Budin WC, Hoskins CN, Haber J, et al. Breast cancer: education, counseling, and adjustment among patients and partners: a randomized clinical trial. Nurs Res. 2008;57:199-213.

- Lee JY, Park HY, Jung D, et al. Effect of brief psychoeducation using a tablet PC on distress and quality of life in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: a pilot study. Psychooncology. 2014;23:928-935.

- Jones JM, Cheng T, Jackman M, et al. Getting back on track: evaluation of a brief group psychoeducation intervention for women completing primary treatment for breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2013;22:117-124.

- Dastan NB, Buzlu S. Psychoeducation intervention to improve adjustment to cancer among Turkish stage I-II breast cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:5313-5318.