Background: Navigation programs are generally characterized as providing patient-centered support and guidance intended to help patients and family members overcome barriers such as timely diagnosis resolution, patient satisfaction, coping with primary and adjuvant treatment, management of side effects, and patient engagement in the healthcare process. The aim of this study was to examine the associations between the Independent Specialty Medical Advocate (ISMA) model of patient navigation and intermediate patient health outcomes for newly diagnosed cancer patients.

Methods: A pre-post intervention study was conducted in 26 newly diagnosed cancer patients recruited from a national partnership between the LIVESTRONG Cancer Navigation Service Program and the NavigateCancer Foundation between April 2013 and December 2015. Participants received a 1-hour initial telephone consultation, and then a navigation care plan was developed for the 6-week study period. A paired t-test was conducted to assess changes in intermediate health outcomes at baseline and 6 weeks after study intervention.

Results: The majority of study participants were males (62%), married (50%), and Caucasian (69%). Overall, there was a statistically significant reduction in anxiety at 6 weeks postintervention (mean, 2.48; SD, 0.62; P <.05) compared with baseline (mean, 2.92; SD, 0.82) and in depression at 6 weeks postintervention (mean, 2.00; SD, 0.81; P <.05) compared with baseline (mean, 2.45; SD, 0.19).

Conclusion: The ISMA model of patient navigation appears to be associated with significant reduction in anxiety and depression. Further studies are needed to evaluate the ISMA model of patient navigation on long-term patient outcomes.

Contemporary cancer care is extraordinarily complex. Cancer patients must digest complicated medical information, grapple with difficult life-altering treatment decisions, and navigate a fragmented healthcare system.1 Patient navigation can help patients and family members throughout the cancer care journey by providing tangible assistance and emotional support.1 The principles of patient navigation are founded on patient-centeredness, with timely access to cost-effective, seamless, and expert care.2,3 Navigators guide patients through the unfamiliar terrain of modern cancer care, answering their questions, and functioning as a reassuring presence.3

Recently, the Commission on Cancer, the oncology accrediting program of the American College of Surgeons, established standards for patient navigation services and psychosocial screening and care for cancer programs seeking approval in 2015.4 In addition, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) requires that, 1) states establish exchanges to facilitate access to health insurance coverage for individuals, and 2) state health insurance exchanges establish a “navigator program” to help individuals make informed decisions about enrolling in health insurance through the exchange.4 Although, the ACA and the Commission on Cancer make references to patient navigation, these programs take many different forms.

Navigation programs are generally characterized as providing patient-centered support and guidance intended to help patients overcome barriers to: 1) timely diagnosis resolution, 2) patient engagement in the healthcare process, 3) patient satisfaction, and 4) cost-effective care.4 Within this broad context, the roles of patient navigators can vary, and programs have adopted varying models of patient navigation to suit their needs and resources. In many instances, patient navigators can work within a medical center where they help patients with care coordination. Patient navigators also often provide advocacy services, which commonly involve communicating with patients by telephone or electronic means. In this instance, patients are assisted in obtaining and synthesizing information, thus promoting informed decision-making and improved receipt of appropriate support services. The promise of both patient navigation and patient advocacy is substantial, yet there remains much to be learned regarding what services are most relevant in the context of specific populations, and how those services may be optimally delivered to positively influence patient outcomes.

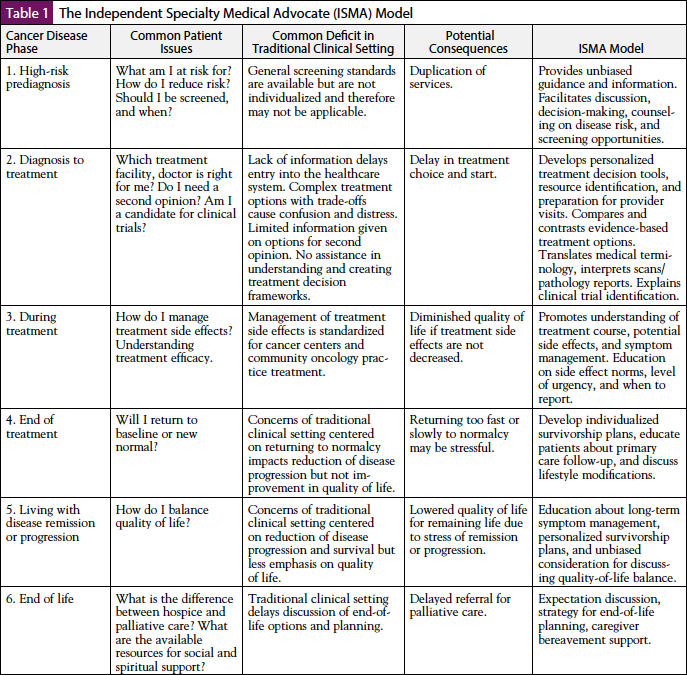

The Independent Specialty Medical Advocate (ISMA) model (Table 1) was developed to provide cancer navigation support services outside of the traditional clinical setting.5 Patient navigation services typically are based in clinical or hospital settings, and patients with cancer are referred to the navigation program by physicians or by clinic-based staff.1,6,7 Patient navigation, an intervention focused on health access barriers, is becoming increasingly adopted as a healthcare delivery innovation to address disparate cancer-related health outcomes.7 However, as the patient navigation program became integrated into the traditional cancer treatment setting across the country, deficits within the traditional clinical setting and lack of comparable metrics to evaluate these programs with a diverse population impeded the ability to identify best practices.7 The ISMA model intervenes on traditional clinical setting deficits by providing unbiased guidance through 6 stages of the cancer experience: 1) high-risk prediagnosis, 2) diagnosis to treatment, 3) during treatment, 4) end of treatment, 5) living with disease remission or progression, and 6) end of life.5 The 4 pillars of the ISMA model of patient navigation are education, advocacy, support, and resource identification.5 Thus, the current study examined the associations between the ISMA model of patient navigation on intermediate patient health outcomes (ie, satisfaction with cancer-related care, coping, anxiety, depression, and self-efficacy) for newly diagnosed cancer patients.

Methods

Study Design

A pre-post intervention study of 26 newly diagnosed cancer patients was conducted. Participants who contacted the LIVESTRONG Cancer Navigation Service program (henceforth LIVESTRONG Navigation) for navigation assistance between April 2013 and December 2015 were invited to participate in the study. LIVESTRONG Navigation provides services independent of any clinic or hospital, and the program is designed to address the needs of patients with cancer and survivors across their cancer journey from diagnosis through posttreatment survivorship.1 The Navigate-Cancer Foundation (NCF) developed a national partnership with LIVESTRONG Navigation to provide cancer patients with advocacy services, information about cancer diagnosis/treatment options, goal setting for care, management of side effects, and advice about second opinions.1 NCF’s mission is to improve cancer care by providing easily accessible cancer navigation tools and services that promote health literacy and self-advocacy for patients and their families. Eligibility criteria included: 1) new diagnosis of cancer, 2) age ≥35 years, 3) English speaking, and 4) patients had to have computer and telephone access for completion of the study survey and navigation. Participants were excluded for: 1) predefined institutional navigation services, 2) metastatic cancer, 3) committed or begun treatment, and 4) difficulty communicating on the phone. To encourage participation, a $20 incentive was provided to all participants. Details of the procedures, risks, and benefits of the study were presented to each participant at the time consent was obtained. The study protocol was approved by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Review Board (#13-3264).

Intervention

Participants received a 1-hour initial telephone consultation, and then a care plan was developed for the 6-week study period. On average, participants received 4 telephone counseling sessions and 18 online navigation sessions by the same nurse consultant. Three nurse consultants serviced participants and divided time equally among study participants. Topics covered in the telephone counseling and online navigation sessions included: 1) needs assessments, 2) decisional counseling/decisional reinforcement focused on treatment decision, 3) coping with primary and adjuvant treatment, 4) health behavior change and goal setting, 5) management of side effects, 6) advice about second opinions, 7) communication strategies for family, and 8) clinical trial education and matching.8 Nurse navigators have formal academic training in oncology nursing (a minimum of a bachelor of science degree in nursing), and a minimum of 5 years of experience with direct patient care in oncology.

Data Collection

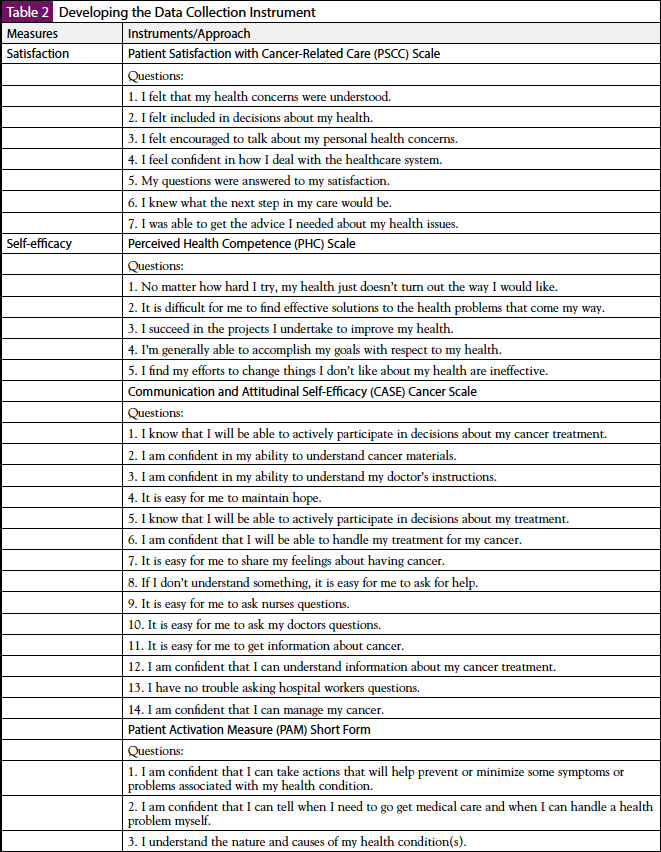

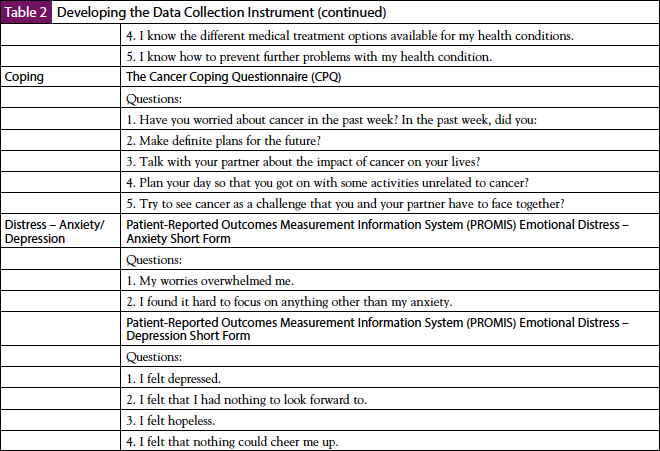

The online survey was delivered via Qualtrics, and participants were surveyed at 2 time points—a baseline assessment at enrollment and again at 6 weeks after study intervention. The assessment of intermediate health outcomes was evaluated with the following previously validated survey instruments (Table 2) detailed below.

The Patient Satisfaction with Cancer-Related Care (PSCC) measure was developed to access satisfaction with care during evaluation of screening abnormalities and treatment.9-11 Patients responded to each scale item on a 5-point Likert scale anchored by “strongly agree” (1) to “strongly disagree” (5), with lower scores indicating higher satisfaction.9 The Communication and Attitudinal Self-Efficacy (CASE) scale for cancer was designed specifically for cancer patients and focus on 3 domains that reflect the roles patients are often expected to fulfill during cancer care: 1) seeking and obtaining information, 2) understanding and participating in care, and 3) maintaining a positive attitude.12 CASE items were accessed on a 5-point Likert scale anchored by “strongly agree” (1) to “strongly disagree” (5), with lower scores indicating higher self-efficacy. The Perceived Health Competence (PHC) scale was developed to provide a measure of perceived competence in effectively managing health outcomes.13 PHC items were evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale anchored by “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5), with lower scores indicating higher self-efficacy.

The Patient Activation Measure (PAM) Short Form assesses patient knowledge, skills, and confidence for self-management.14 PAM items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale anchored by “strongly agree” (1) to “strongly disagree” (5), with lower scores indicating higher patient activation. The Cancer Coping Questionnaire (CCQ) measures the extent to which patients learn to use cognitive, behavioral, and emotional strategies to cope with cancer treatment.15 CCQ items were measured on a 4-point Likert scale anchored by “very often” (1) to “not at all” (4), with lower scores indicating higher coping with cancer treatment.

The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Emotional Distress – Short Form (SF) 8 anxiety and depression measures patient fear, worries, helplessness, and hopelessness within the past 7 days.16 PROMIS anxiety and depression items were evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale anchored by “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5), with lower scores indicating higher anxiety and depression.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, means, and standard deviations were calculated to summarize participant characteristics. A paired t test was conducted to assess changes in participants’ intermediate health outcomes at baseline and 6 weeks after the study intervention. All analyses were conducted using Stata statistical software (version 13).

Results

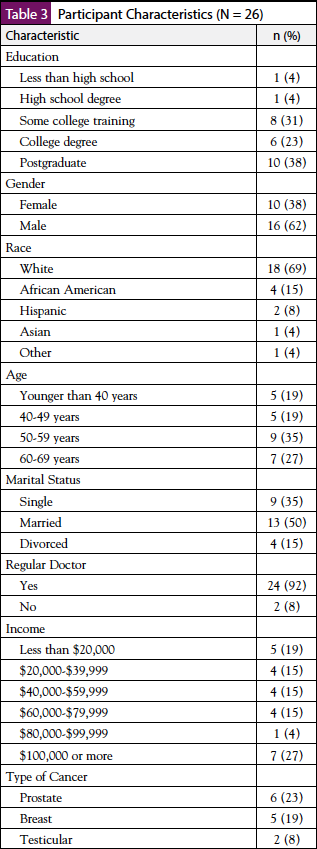

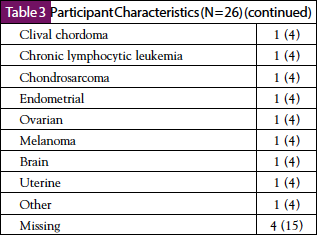

Table 3 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants. The majority of study participants were males (62%), married (50%), white (69%), aged 60 to 69 years (27%), with an annual income of $100,000 or more (28%). Ninety-two percent had a regular doctor, and 38% had a postgraduate education. Further, participants were most commonly diagnosed with prostate (23%) and breast (19%) cancer.

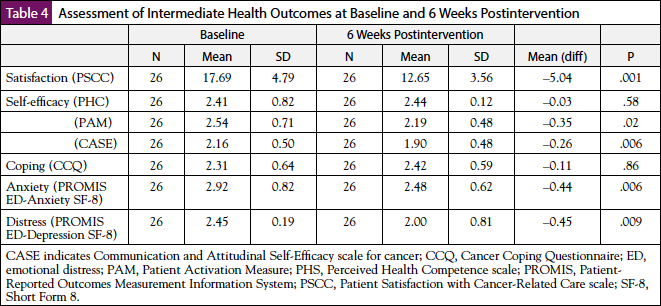

Table 4 shows assessment of intermediate health outcomes at baseline and 6 weeks postintervention. There was a statistically significant reduction in anxiety at 6 weeks postintervention (mean, 2.48; SD, 0.62; P <.05) compared with baseline (mean, 2.92; SD, 0.82) and in depression at 6 weeks postintervention (mean, 2.00; SD, 0.81; P <.05) compared with baseline (mean, 2.45; SD, 0.19). There was no statistically significant difference in coping at baseline and 6 weeks postintervention.

Further, there was a statistically significant increase in satisfaction with cancer-related care at 6 weeks postintervention (mean, 12.65; SD, 3.56; P <.05) compared with baseline (mean, 17.69; SD, 4.79) and in communication and attitudinal self-efficacy at 6 weeks postintervention (mean, 1.90; SD, 0.48; P <.05) compared with baseline (mean, 2.16; SD, 0.50).

Discussion

Growing support exists for patient navigation in cancer care, yet much remains to be learned regarding what services are most relevant in the context of specific populations, and how those services may be optimally delivered to positively influence patient outcomes. In the current study, we assessed the associations between the ISMA model of patient navigation and intermediate patient health outcomes using a pre-post intervention study of 26 newly diagnosed cancer patients. There was a statistically significant reduction in anxiety and depression at 6 weeks postintervention compared with baseline. These findings were consistent with other studies assessing the impact of patient navigation on improving patient psychosocial outcomes. Treiman and colleagues addressed the psychosocial needs of cancer patients from diagnosis through posttreatment survivorship and the implications of patient navigation services outside the traditional clinical setting.1 The authors found that emotional distress decreased from study intake and 6 weeks after intake, and patients who had an emotional support navigator had a significant reduction in cancer-related concerns.1 Further, participants who had an emotional support navigator reported confidence in their ability to get emotional support, to talk with healthcare providers about personal problems related to their diagnosis, and to take action to make themselves feel better.1

Madore and colleagues conducted a feasibility study to understand the relationship between patient-reported barriers and patient-reported psychosocial distress in underserved women recently diagnosed with breast cancer. The authors found a significant relationship between depression and several patient-reported barriers, such as difficulty making a treatment decision, negative emotional reaction to treatment, and insufficient social support.8 Furthermore, the authors concluded that navigation interventions that assist patients in identifying reliable sources of social support may provide an important mechanism to overcoming several common barriers to receiving beneficial cancer treatment.8

The findings of the current study have immediate implications for the implementation of patient navigation in cancer care. The American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer has established standards for patient navigation services and psychosocial screening and care for cancer programs seeking approval.4,17,18 However, these patient navigation programs take many different forms. The ISMA model of patient navigation lessens traditional clinical setting deficits by providing unbiased, easily accessible guidance throughout the cancer care continuum through education, advocacy, support, and resource identification.

In addition, our study also found a statistically significant increase in satisfaction with cancer-related care and communication and attitudinal self-efficacy at 6 weeks postintervention compared with baseline. This finding was inconsistent with other studies reporting on satisfaction with cancer-related care using a patient navigation intervention. Post and colleagues investigated the effects of a telephone-based patient navigation intervention on satisfaction with cancer-related care as reported by individuals with abnormal breast, cervical, or colorectal cancer screening test results.19 The project was 1 of 9 studies in the national Patient Navigation Research Program (PNRP), funded by the National Cancer Institute and the American Cancer Society, aimed to test patient navigation interventions intended to reduce or eliminate cancer health disparities.19 Further, the PSCC questionnaire was used to evaluate satisfaction with care at 3 different time points after patients received a positive screening test for cancer: 1) during their most recent visit, 2) after their most recent visit, and 3) at all visits since receiving a positive screening test for cancer.19 The authors found no significant difference between the intervention and control groups in mean increases in PSCC from baseline to end of the study (3.26 vs 2.53, respectively; P = .43).

Wells and colleagues found that patients who participated in the PNRP were highly satisfied with their cancer-related care, irrespective of their allocated group (ie, patient navigation or control).20 The authors evaluated the effect of patient navigation on satisfaction with cancer-related care using the PSCC. However, this study differed from the study by Post and colleagues in that it was a larger multisite sample of 2539 participants, had a diverse group of participants that included English and Spanish speakers, and used a concurrent control group and validated measure of satisfaction. A few studies previously proposed protocols to investigate the impact of patient navigation interventions on communication and attitudinal self-efficacy.21,22 However, the results of the CASE scale from these studies were not published.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, most study participants were well educated, limiting generalizability to populations with lower educational status. Second, the pre-post intervention study design did not include a comparative arm; therefore, we must consider the findings about the impact of the ISMA model of patient navigation to be suggestive. And third, because of the small sample size, analyses focused on pre-post differences in mean to describe the feasibility of the ISMA model of patient navigation.

Conclusion

The ISMA model of patient navigation appears to be associated with a significant reduction in anxiety and depression and a significant increase in satisfaction with cancer-related care and communication and attitudinal self-efficacy for newly diagnosed cancer patients. The scope of practice for nurse navigators can be expanded to include independent navigators to provide evidence-based interventions to improve cancer care outcomes. Increasing demands on oncologists within the traditional clinical setting and multiple demands on patients to comprehend the cancer care continuum are widening the gaps for satisfaction with cancer-related care. Therefore, an ISMA model of patient navigation has clinical practice implications providing additional support for cancer patients. The ISMA model intervenes on traditional clinical setting deficits by providing unbiased guidance from prediagnosis, treatment, living with disease remission or progression, and end of life. Further studies are needed to determine the impact of the ISMA model of patient navigation on long-term patient outcomes.

Author Contributions

Ewan K. Cobran, Beth Roach, Sharon M. Bigelow, and Paul A. Godley contributed to the conception and design of this article. Ewan K. Cobran, Yesenia Merino, Beth Roach, and Sharon M. Bigelow contributed to the collection and assembly of data. Ewan K. Cobran, Yesenia Merino, Beth Roach, Sharon M. Bigelow, and Paul A. Godley contributed to the data analysis and interpretation. All authors contributed to the final approval of this article.

Funding

Ewan K. Cobran was supported by a grant from the NavigateCancer Foundation, award 25210-49200-8775055, made to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, for the work performed as part of the current study.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

Ewan K. Cobran was supported by a grant from the NavigateCancer Foundation for the work performed as part of the current study.

References

- Treiman K, Bann C, Squiers L, et al. Cancer support services outside of clinical settings: an evaluation of LIVESTRONG Foundation’s Cancer Navigation Program. Journal of Oncology Navigation & Survivorship. 2015;6(3):8-17.

- Freeman HP. The history, principles, and future of patient navigation: commentary. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2013;29:72-75.

- Gotlib Conn L, Hammond Mobilio M, Rotstein OD, et al. Cancer patient experience with navigation service in an urban hospital setting: a qualitative study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2016;25:132-140.

- Institute of Medicine. Patient-Centered Cancer Treatment Planning: Improving the Quality of Oncology Care. Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011.

- Bigelow S, Roach B. The independent specialty medical advocate: a new nursing service model. Paper presented at: American Academy of Nursing 40th Annual Meeting and Conference; October 17-19, 2013; Washington, DC.

- Battaglia TA, Burhansstipanov L, Murrell SS, et al. Assessing the impact of patient navigation: prevention and early detection metrics. Cancer. 2011;117(15 Suppl):3553-3564.

- Guadagnolo BA, Dohan D, Raich P. Metrics for evaluating patient navigation during cancer diagnosis and treatment: crafting a policy-relevant research agenda for patient navigation in cancer care. Cancer. 2011;117(15 Suppl):3565-3574.

- Madore S, Kilbourn K, Valverde P, et al. Feasibility of a psychosocial and patient navigation intervention to improve access to treatment among underserved breast cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:2085-2093.

- Jean-Pierre P, Fiscella K, Winters PC, et al. Psychometric development and reliability analysis of a patient satisfaction with interpersonal relationship with navigator measure: a multi-site patient navigation research program study. Psychooncology. 2012;21:986-992.

- Jean-Pierre P, Fiscella K, Freund KM, et al. Structural and reliability analysis of a patient satisfaction with cancer-related care measure: a multisite patient navigation research program study. Cancer. 2011;117:854-861.

- Jean-Pierre P, Cheng Y, Wells KJ, et al. Satisfaction with cancer care among underserved racial-ethnic minorities and lower-income patients receiving patient navigation. Cancer. 2016;122:1060-1067.

- Wolf MS, Chang CH, Davis T, et al. Development and validation of the Communication and Attitudinal Self-Efficacy scale for cancer (CASE-cancer). Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57:333-341.

- Smith MS, Wallston KA, Smith CA. The development and validation of the Perceived Health Competence Scale. Health Educ Res. 1995;10:51-64.

- Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stockard J, et al. Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6 Pt 1):1918-1930.

- Moorey S, Frampton M, Greer S. The Cancer Coping Questionnaire: a self-rating scale for measuring the impact of adjuvant psychological therapy on coping behaviour. Psychooncology. 2003;12:331-344.

- Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005-2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1179-1194.

- Battaglia TA, Darnell JS, Ko N, et al. The impact of patient navigation on the delivery of diagnostic breast cancer care in the National Patient Navigation Research Program: a prospective meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;158:523-534.

- Ko NY, Snyder FR, Raich PC, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in patient navigation: results from the Patient Navigation Research Program. Cancer. 2016;122:2715-2722.

- Post DM, McAlearney AS, Young GS, et al. Effects of patient navigation on patient satisfaction outcomes. J Cancer Educ. 2015;30:728-735.

- Wells KJ, Winters PC, Jean-Pierre P, et al. Effect of patient navigation on satisfaction with cancer-related care. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:1729-1753.

- Hendren S, Griggs JJ, Epstein RM, et al. Study protocol: a randomized controlled trial of patient navigation-activation to reduce cancer health disparities. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:551.

- Nonzee NJ, McKoy JM, Rademaker AW, et al. Design of a prostate cancer patient navigation intervention for a Veterans Affairs hospital. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:340.