We all know that being physically active and participating in exercise is beneficial to overall health and well-being for numerous reasons. Surprisingly and unfortunately, education on the physiological, clinical, and psychological benefits of being active is not standard in nursing or physician curriculum. In terms of the general population, the benefits are readily accepted and not really questioned. However, in terms of the oncology population, the benefits, feasibility, and facilitation of exercise may be questioned by oncology professionals. What may go amiss is the fact that exercise for the oncology patient is supported by evidence-based research and randomized controlled studies.

May we ask you 4 questions about exercise and oncology?

TAKE OUR SURVEY!Results will be published in the next issue of JONS

The Evidence

There has been exponential growth in the exercise oncology field, and it is not slowing down. The theory of exercise being beneficial to the oncology patient was present before the 1980s; however, the first recorded randomized control study was conducted at this time by 2 nurse pioneers, Drs Winningham and MacVicar. The study validated the feasibility and safety of aerobic training in breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy as well as its positive effects on aerobic capacity, body composition, and patient-reported nausea. This study was a pivotal point in exercise oncology history and eye-opening to oncology professionals because it was common practice to encourage patients to rest, conserve energy, and get back to healthy lifestyle habits once they were done with treatment and in the late survivorship phase.1-3

Exercise oncology research continued, and in 2010 the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) reviewed available studies and published the first Exercise Guidelines for Cancer Patients. These guidelines confirmed the safety of exercise throughout the cancer care continuum—a common concern and implementation barrier—and recommended patients participate in the same activity recommendations as the general public.4 Exercise oncology research exploded 281% between 2010 and 2018. In 2019, ACSM updated the Exercise Guidelines for Cancer Patients. These guidelines took it a step further and confirmed that there was strong evidence to support exercise decreasing anxiety, depression, and cancer-related fatigue as well as improving quality of life and physical functioning. They supported the safety of exercise if one is at risk for breast cancer–related lymphedema.5 They validated the meaningful impact of exercise in relation to prevention of 7 cancers (bladder, breast, colon, endometrial, esophageal, kidney, and stomach) and reduction of cancer-specific or all-cause mortality in breast, colon, and prostate cancer.6,7

The Recommendations

Because the updated 2019 guidelines dove deeper into the impact of exercises on specific treatment-related side effects, there is some variation in what activity is recommended based on which side effect one is targeting.8 Overall, the recommendation is to avoid inactivity and try to participate in 150 minutes/week of aerobic exercise and 2 strength training days/week. Strength training days should include 2 sets of 8 to 15 repetitions for the major muscle groups.5,8

It is crucial to meet the patients where they are at functionally. The recommendations serve as an overarching goal, but functional level will dictate where the starting line should be. For example, a patient who has not participated in physical activity for months and is currently receiving chemotherapy may have a goal to walk for 5 minutes 3 times a day, 3 days a week and progressively work up from there. When a patient is on cyclic treatment, being mindful of when symptoms are at the highest level will help determine when to decrease duration or intensity in their exercise program so that they are still moving but not doing too much. As a guide, a patient should feel more energized after movement and not more tired.

Implementation Barriers

Despite the established guidelines and support from ACSM, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network,9 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO),10 and American Cancer Society11 to implement exercise into oncology standard of care, exercise referrals remain low. Based on an ASCO survey, only 14.9% of patients were referred to exercise programs even though exercise was addressed at most or some oncology visits (57.5%) of respondents.12

A meta-analysis investigated barriers to implementation of exercise into oncology practice. Six categories were developed (listed in highest to lowest frequency): organizational context (nearly 40%), individual professionalism, innovation, patient, economic and political context, and social context. Barrier categories are a structural way to divide the information collected; however, they are not necessarily to be viewed as separate since they are interrelated. To address organizational context, innovation and individual professionalism may also need to be addressed. The interrelated web of barriers makes it complex to pinpoint implementation solutions.13 What can oncology nurse navigators (ONNs) take away from this study, and how can they help? Each category involved a lack of knowledge and education (both in healthcare professionals and patients) on exercise benefits and/or recommendations in some capacity, supporting the need for appropriate and effective dissemination of exercise oncology research and guidelines.

The Navigator’s Role

ONNs are strategically placed to intercept patients at multiple stages in the continuum. Navigators also collaborate with and coordinate between different multidisciplinary teams, including oncology care team clinicians, rehabilitation services, general practitioners, and integrative medicine programs. For both reasons, the ONN may play an instrumental role in dissemination of exercise education and guidelines to healthcare professionals, patients, and families, as well as facilitation of referrals to rehabilitation or cancer exercise professionals.

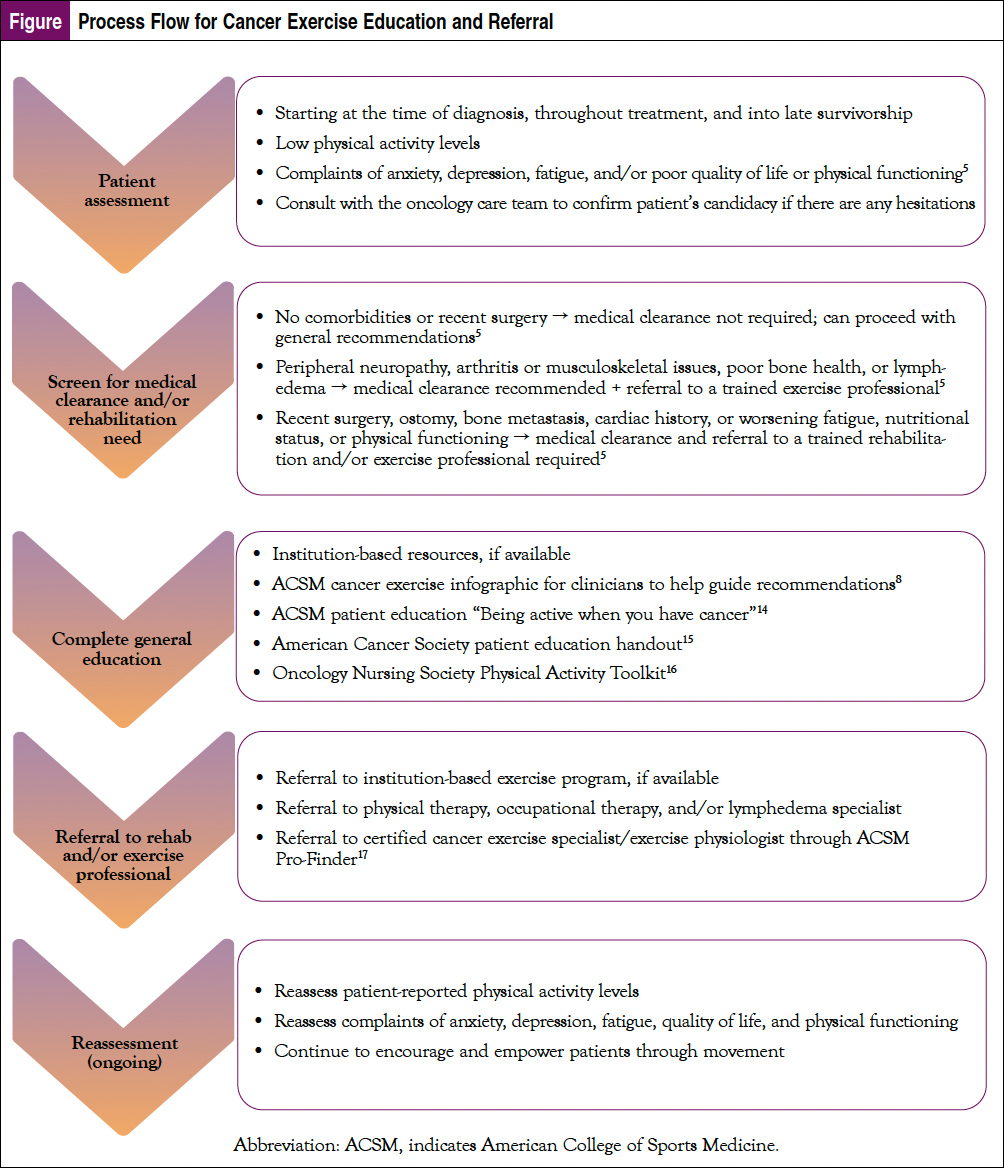

ONNs can increase patient education and referrals (Figure), develop institution-based patient education, and advocate for physical activity and exercise to be included in standard-of-care treatment recommendations. ONNs can speak with leadership about nurse-led research opportunities or quality improvement initiatives to further evolve the field of exercise oncology.

Summary

As ONNs, we want patients to get through treatment as best as possible. We collaborate with the care team and help guide recommendations to mitigate or treat side effects. Exercise can serve as an invaluable intervention to empower patients, improve treatment toleration and overall outcomes, and, most importantly, improve the overall quality of life in the patients we serve.

May we ask you 4 questions about exercise and oncology?

TAKE OUR SURVEY!Results will be published in the next issue of JONS

References

- Jones LW, Alfano CM. Exercise-oncology research: past, present, and future. Acta Oncol. 2012;52:195-215.

- Winningham ML, MacVicar MG, Bondoc M, et al. Effect of aerobic exercise on body weight and composition in patients with breast cancer on adjuvant chemotherapy. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1989;16:683-689.

- Winningham ML, MacVicar MG. The effect of aerobic exercise on patient reports of nausea. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1988;15:447-450.

- Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, et al. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42:1409-1426.

- Campbell KL, Winters-Stone KM, Wiskemann J, et al. Exercise guidelines for cancer survivors: consensus statement from international multidisciplinary roundtable. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51:2375-2390.

- Patel AV, Friedenreich CM, More SC, et al. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable report on physical activity, sedentary behavior, and cancer prevention and control. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51:2391-2402.

- Schmitz KH, Campbell AM, Stuiver MM, et al. Exercise is medicine in oncology: engaging clinicians to help patients move through cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:468-484.

- American College of Sports Medicine. Effects of exercise on health-related outcomes in those with cancer. www.acsm.org/docs/default-source/files-for-resource-library/exercise-guidelines-cancer-infographic.pdf?sfvrsn=c48d8d86_4.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Cancer-Related Fatigue. Version 2.2023. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/fatigue.

- Ligibel JA, Bohlke K, May AM, et al. Exercise, diet, and weight management during cancer treatment: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:2491-2507.

- Nutrition and physical activity guideline for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72:263-265.

- Ligibel JA, Pierce LJ, Bender CM, et al. Attention to diet, exercise, and weight in the oncology clinic: results of a national patient survey. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(suppl 15). Abstract 10549.

- Kennedy MA, Bayes S, Newton RU, et al. Implementation barriers to integrating exercise as medicine in oncology: an ecological scoping review. J Cancer Surviv. 2022;16:865-881.

- American College of Sports Medicine. Being active when you have cancer. www.exerciseismedicine.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/EIM_Rx-for-Health_Cancer.pdf. Published 2021.

- American Cancer Society. Physical Activity and the Person with Cancer. www.cancer.org/treatment/survivorship-during-and-after-treatment/be-healthy-after-treatment/physical-activity-and-the-cancer-patient.html. Revised March 16, 2022. Accessed April 1, 2023.

- Oncology Nursing Society. Get Up, Get Moving. www.ons.org/make-a-difference/quality-improvement/get-up-get-moving. Published 2023.

- American College of Sports Medicine. ProFinder. https://certification2.acsm.org/profinder?_ga=2.139239987.1600007473.1525799292-1759941655.1523997371. Published 2020.