Purpose: Develop and implement a comprehensive program for lifestyle change, empowering breast cancer patients to manage stress effectively and improve their mental and physical health.

Method: Women with breast disease (or those at high risk) are offered a program of lifestyle change, consisting of a healthy lifestyle intervention for 3 months followed by monthly contact with a health coach. Instruction and demonstration provide information on exercise, nutrition, stress reduction, and mind/body health. Examinations are conducted at baseline, after completion of the intervention (3 months), at 1 year, and every 6 months for a period of 5 years.

Conclusion: Breast cancer has a significant emotional, psychological, and social impact and is often associated with high levels of stress that promote unhealthy behaviors causing weight gain, decreased physical fitness, and an increased risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD). Similar to CVD, research shows breast cancer susceptibility is also influenced in part by modifiable risk factors, suggesting that a healthy lifestyle program may lead to reductions in cancer risk and recurrence as well as improvements in mental health and quality of life. Through the Stress Therapy Empowering Prevention (STEP) program, breast cancer and highrisk patients are empowered with tools to focus on health promotion and optimization and maintenance of quality of life. Patients can improve physical and psychosocial factors in as little as 3 months, but long-term follow-up will determine if lifestyle changes result in improved clinical outcomes over time.

Extensive reports have documented the relationship between lifestyle changes and morbidity/ mortality associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD). In particular, diet, physical activity, and stress are known to be associated with cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.1-3 Similar to CVD, evidence has been mounting that breast cancer susceptibility is influenced in part by modifiable risk factors, such as body weight, diet, and physical activity, suggesting that a healthy lifestyle program may lead to a reduction in risk factors for CVD and breast cancer. Improving health and quality of life in patients with CVD and breast cancer will result in improved outcomes of care over the long term.

Early diagnosis and treatment are still vital to surviving breast cancer. Although an estimated 192,370 new cases of invasive breast cancer were expected in 2009, with approximately 40,170 deaths from the disease, incidence rates actually decreased by 2.0% per year,4 likely due to advanced screening and early detection. In an effort to continue to lower incidence rates and improve long-term outcomes, studies of behavior modification in breast cancer patients are providing new information about how lifestyle factors affect survivorship as well as knowledge to help develop new, effective intervention programs to decrease breast cancer risk.5-11

The Stress Therapy Empowering Prevention (STEP) program is an innovative approach based on the concept that comprehensive lifestyle changes may have a meaningful impact on the risk for developing breast and cardiac disease. Given the advantages of a healthy lifestyle on both physical and emotional outcomes, cancer patients as well as those at high risk should be urged to address unhealthy behaviors. Our STEP model utilizes a specialized team comprising physicians, nurses, dietitians, licensed therapists, exercise physiologists, and stress management specialists who provide comprehensive strategies that empower the participant to make healthier choices at an individual level. The program is an adjunct to treatment and care that participants receive from their personal healthcare providers. This combined effort allows for closer monitoring of each participant and coordination of care across the healthcare spectrum to achieve optimal health and quality of life.

METHODS

The overall goal is to recruit and evaluate approximately 500 women diagnosed with, or at high risk for, both breast and cardiac disease. The objectives of the study are to (1) test the efficacy of a healthy lifestyle intervention on reducing stress, sleep disturbances, and cardiovascular risk factors in both high-risk patients and patients diagnosed with breast disease; (2) evaluate the long-term benefit of an enhanced health coach intervention in promoting sustained wellness behaviors; and (3) examine molecular markers common to atherosclerosis and cancer to assess longitudinal changes and their relationship to disease development.

The STEP program has a 3-month healthy lifestyle intervention period during which participants meet once a week to learn the program guidelines, which include a low-fat, whole food nutrition plan based on the Mediterranean diet, aerobic and strength training exercises, stress management, and weekly mind/body health sessions. After the initial 3-month period, participants are contacted on a monthly basis by a health coach to ensure that program compliance is being maintained and to assist with long-term adherence. Participants are required to return to the center at the 1-year time point, and every 6 months thereafter for a period of 5 years, for testing and evaluation. Information collected includes perceived stress, sleep disturbance, psychosocial measurements, carotid ultrasound to measure carotid intima-media thickness, traditional risk factors (weight, blood pressure, body mass index [BMI], body composition), and biochemical assays.

To be eligible to participate, women must be 18 years of age or older with a diagnosis of breast disease (atypical hyperplasia, in situ carcinoma, or invasive breast cancer) or significant risk factors for developing breast disease such as previous biopsy, family history of breast disease, first pregnancy after the age of 30, early menstruation or late onset of menopause, or high risk of developing coronary artery disease (CAD) as indicated by having 1 or more of the following: family history of CAD, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, elevated blood lipids, sedentary lifestyle and obesity, or established clinically stable coronary disease.

Participants begin the program with an extensive physician visit to conduct a comprehensive risk assessment and develop a realistic lifestyle change plan. Participants are interviewed to assess sleep patterns, smoking status, cardiovascular and breast history, and medication use. The clinical exam includes height and weight measurements to calculate BMI (kg/m2); blood profiles including thyroid-stimulating hormone, comprehensive metabolic panel, and fasting glucose and lipid panel; systolic and diastolic blood pressures; and psychological screening to evaluate mental health. Assessments are repeated at the end of the healthy lifestyle intervention, at year 1, and every 6 months thereafter for a period of 5 years.

Following the initial examinations, participants attend an educational workshop designed to provide further instruction regarding the recommended lifestyle changes, followed by once-aweek sessions over a 3-month period. These sessions are tailored to ensure that each individual receives the appropriate education and experience needed to achieve success. Participants are required to complete a personal awareness log each week, which includes documentation of diet, exercise, and stress management frequency and duration, and a self-report of their mind/body session experience.

Blood samples are obtained from each consenting individual at baseline, at completion of the healthy lifestyle intervention, at 1 year, and every 6 months thereafter for a period of 5 years. From the blood samples, the following biochemical assays are analyzed: (1) lipoprotein subclass distributions determined by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy; (2) stress/CVD biomarker panel: serum cortisol, insulin, leptin, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, lipo - protein(a), adiponectin, resistin, serum amyloid A, and vitamin D; and (3) breast disease–related panel: HER2/neu, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha, and estradiol. In addition, blood is collected for isolating messenger RNA to determine changes in gene expression over the course of the study and identify new molecular markers associated with improved CVD biomarker risk profiles.

RESULTS

Recruitment is being conducted primarily through newspaper and radio ads; distribution of patient information brochures; and speaking engagements at various community education events, physician offices, and support groups. Of 43 women who initially expressed interest in the program, 18 have enrolled thus far. Average age of participants was 65 years. Of the 18 participants enrolled in the program, 11 women had diagnosed breast disease (61%). In addition, of these same 18 women, 17 (94%) were also considered at high risk for developing CVD by having at least 1 documented CAD risk factor. Overall attendance was 88% during the initial 3-month on-site sessions. Four participants (22%) discontinued participation in the program, 3 due to personal, nonmedical reasons, and 1 due to breast cancer progression.

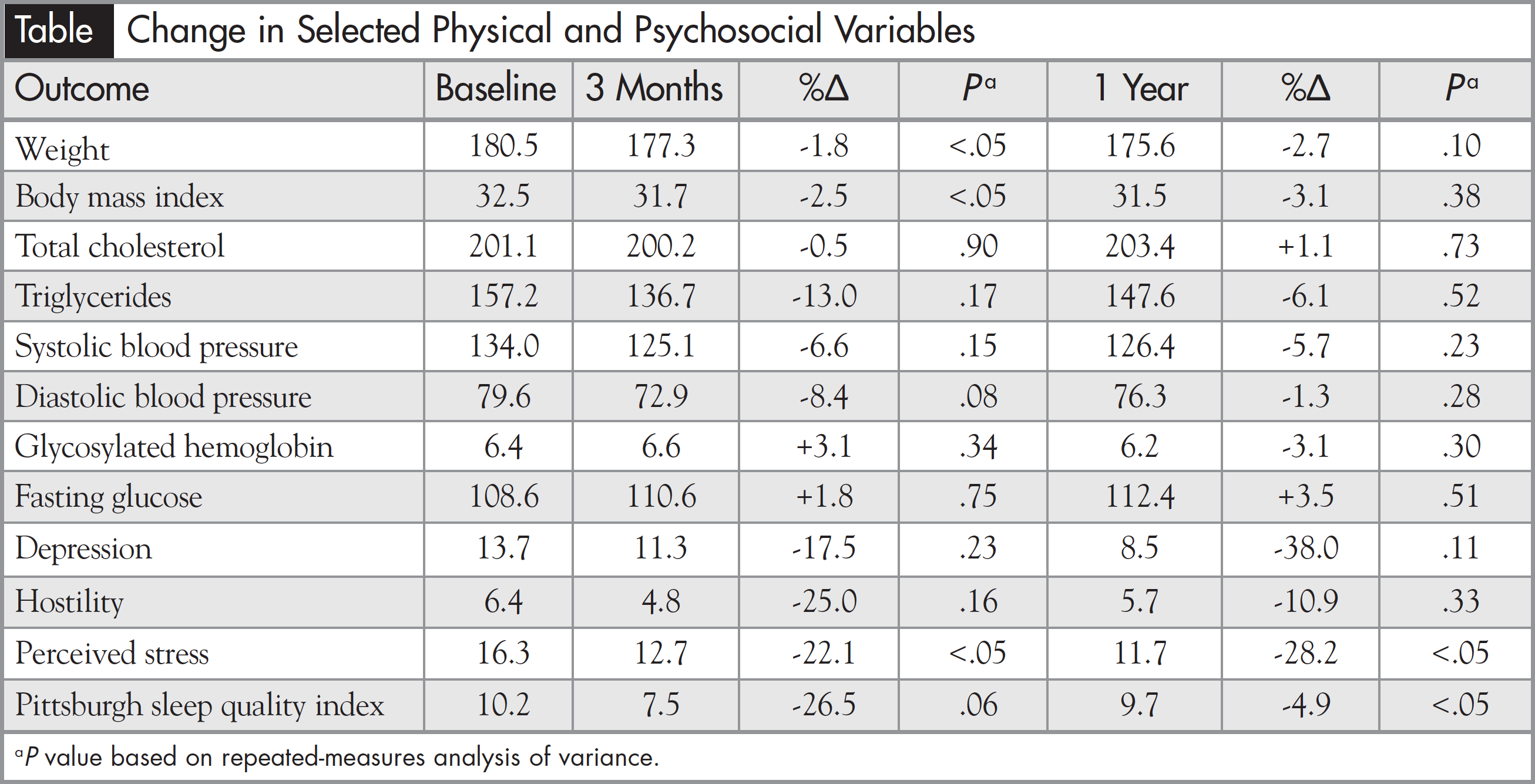

Upon completion of the healthy lifestyle intervention (3 months), participants (n = 14) showed change in the desired direction for many risk factors. Body weight (-1.8%, P <.05), BMI (-2.5%, P <.05), and perceived stress (-22.1%, P <.05) decreased significantly. Diastolic blood pressure (-8.4%, P <.08) and sleep quality (-26.5%, P <.06) showed near-significant changes. Most importantly, at the 1-year time point, perceived stress (n = 10, 8.2%, P <.05) and sleep quality (n = 9, -4.9%, P <.05) improvements were maintained, showing that these positive changes could be maintained over a longer period of time. In addition, though lacking statistical significance with our current sample size, triglycerides, systolic blood pressure, hostility, and depression all decreased at both time points (Table).

Based on self-reported exercise frequency and duration data, at 3 months participants on average were able to increase vigorous activity (heavy lifting, digging, aerobics, or fast bicycling) by 1.13 days/week, moderate activity requiring the participant to breathe somewhat harder than normal (carrying light loads or bicycling at a regular pace) by 1.56 days/week, and walking activity (including walking at work or home for recreation, sport, exercise, or leisure) by 1.63 days/week. At the 1-year time point, participants continued to show increased levels of activity for all measured categories; vigorous activity remained increased by 1.13 days/week, moderate activity by 1.13 days, and walking activity by 0.82 days when compared with baseline activity.

Lipoprotein subclass profiles will be assessed by NMR spectroscopy, which will quantify low-density lipoprotein particle number and size, and provide direct measurement of high-density lipoprotein and very low-density lipoprotein subclasses. Biochemical variables of interest regarding CVD risk, including insulin, leptin, lipoprotein(a), adiponectin, resistin, serum amyloid A, and TNF alpha will permit correlation of traditional CVD risk factors with nontraditional biomarkers to provide more information on the prevention and treatment of CVD. Vitamin D, HER2-neu, and estradiol will be analyzed to provide further insight into breast disease development and progression. Lower serum 25 (OH) D (vitamin D) concentrations may be associated with poorer overall survival and distant disease-free survival in postmenopausal breast cancer patients.12 HER2-neu blood levels have potential as a tumor marker in breast cancer. Many studies have monitored circulating levels after surgery and reported that increasing HER2-neu levels can indicate recurrence of breast cancer earlier than clinical diagnosis.13,14 Estrogens are believed to play a critical role in the etiology of breast cancer, and considerable evidence suggests that lifetime exposure to endogenous hormones, notably estrogens, promotes breast carcinogenesis.15 Finally, cortisol levels, considered a major indicator of altered psychological states in response to stress, may provide information on short- and long-term stressors.16

DISCUSSION

There are no proven substitutes for conventional cancer treatments such as surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, and immunotherapy; however, one approach to gaining a better understanding of how lifestyle change can enhance breast cancer survival is to develop studies that address several behavior and lifestyle factors within the same program. Research has shown that among women with breast cancer who had surgery and conventional treatment, those who learned to change their lifestyle through education focused on better nutrition, more exercise, and stress reduction were 68% less likely to die from disease over an 11-year period than those who did not.17 Although the STEP study currently lacks longterm follow-up data, our program is examining the importance of helping breast cancer patients eat better, lose weight, improve strength and endurance, develop coping skills, and ultimately to improve their overall health and well-being. Participants in a STEP-style program feel better, both physically and emotionally. These observations suggest that the program has potential to improve their long-term overall risk profiles.

An important finding in our study was the struggle encountered in recruiting participants into the program. Obstacles to recruitment included out-of-pocket expenses, lack of local physician referrals, participant time constraints, and lack of knowledge among patients about the benefits of lifestyle change on quality of life or clinical outcomes. However, once women made the commitment to participate, surveys indicated a high degree of satisfaction with the program. Ultimately, issues encountered with recruitment affected our sample size, leading to difficulties in being able to effectively interpret preliminary data. In the future, we will continue to use best clinical judgment on when to approach appropriate patients based on past experience, to repeatedly offer to assist patients with addressing risk factors, and to educate healthcare providers about the STEP program to increase our sample size and provide additional data for analysis of the effects of lifestyle change on breast disease.

NUTRITION

Although the relationship between diet and breast cancer remains unclear, studies have shown that improved nutrition reduces the risk of several chronic diseases, such as obesity, diabetes, and heart disease, and that a healthy lifestyle improves overall quality of life.18,19 Breast cancer patients who practice better nutrition are likely to derive benefit in terms of total mortality, similar to the general population. The Women’s Healthy Eating and Living study showed that women who consumed a healthy diet and were physically active increased survival after diagnosis.20 Patients who reported eating at least 5 servings of fruits and vegetables per day and performing 30 minutes of moderate walking 6 days a week reduced the probability of death by 50%.

The STEP program nutrition plan is based on the Mediterranean diet and recommends eating vegetables; fruits; whole grains; lean protein sources such as fish and nuts; and olive oil; and minimizing the amount of red meat consumed. Participants are counseled to focus on eating more naturally occurring and fewer highly processed foods. Involvement of a registered dietitian helps to guide this process and provides the education, support, and long-term follow-up needed to meet the challenges of sustaining the recommended dietary changes.

The majority of studies of diet and breast cancer have examined the impact of body weight on survival. Most have observed that obesity at diagnosis is associated with poor prognosis.21 Similarly, weight gain after diagnosis is common and is associated with mortality, disease recurrence, and development of comorbid conditions including diabetes and CVD.22 Although some studies have shown that following a prudent diet alone, without adding physical activity, may not be associated with breast cancer survival,5,23 a healthy diet has been shown to have beneficial effects on overall survival in conditions such as diabetes and heart disease, which are frequently seen in breast cancer patients.24

Participants in the STEP program were able to significantly decrease measures of obesity such as weight and BMI within the first 3 months of the program. Although these measures were not statistically significant at 1 year, they continue to remain lower than at baseline, suggesting that participants were successful in meeting or exceeding dietary compliance targets, thus preventing weight gain and promoting weight loss, which has been proven to be an effective strategy for improving overall quality of life and survival.

EXERCISE

Physical activity is as important as diet for achieving optimal weight and maintaining a healthy lifestyle. In studies examining the relationship between physical activity and the risk of breast cancer, a decrease in risk of approximately 25% was found among the most physically active women.25 Similarly, in studies examining the effect of physical activity on breast cancer survival, some studies suggest that postdiagnosis physical activity may have great benefit. One study showed that after diagnosis, physical activity equivalent to walking 3 to 5 hours per week reduced mortality by as much as 50%.26 Although the risk of developing comorbid conditions, including CVD, type 2 diabetes, fatigue, lymphedema, psychological distress, and poor quality of life, often persists in breast cancer survivors, recent studies have shown that physical activity can lower breast cancer risk and provide additional health benefits, such as decreased risk of stroke and type 2 diabetes, and improved longevity and quality of life.27

Most STEP participants achieved improvement in physical activity during the initial 3- month period, and many maintained these initial gains or continued to improve by the end of the first year. While most research demonstrates beneficial effects between physical activity and overall health, it is important to recognize that there is a risk-benefit ratio to exercise that may be different for each breast cancer patient. Utilizing a personalized plan might be most effective because it can be customized for different time periods, from prediagnosis through cancer treatment, based on individual needs and abilities. The STEP program develops each participant’s activity plan based on an individual assessment completed by an exercise physiologist, but generally participants are encouraged to exercise aerobically for a minimum of 30 minutes per day, for a total of 3 hours of aerobic exercise each week. More intense exercise is permitted if medically appropriate and desired by the participant. Resistive or strength training exercise also is important, and if medically appropriate, participants were instructed to engage in strength training exercises 2 to 3 times per week. During the healthy lifestyle intervention portion of the study, hour-long supervised exercise sessions were scheduled.

The objectives of our exercise modality are to fully understand the importance and benefits of regular physical activity, to create a safe environment for exercise, and to encourage participants to properly monitor their own exercise program outside of the STEP program. These activities will assist with long-term adherence and allow the participant to achieve her own physical activity goals.

STRESS MANAGEMENT

Working with participants in the STEP program presents some unique challenges. These women have faced their mortality and live with the ongoing psychological stress of possible cancer recurrence.28 A recent meta-analysis of 10 randomized controlled trials found that cancer patients who participated in yoga interventions showed significant improvement in several psychological measures, including anxiety, distress, depression, and stress compared with wait-list controls.29 For breast cancer survivors in particular, yoga has been shown to improve quality of life and emotional functioning.30

A mild form of physical activity, such as yoga or tai chi, may help to promote regular participation in physical activity. The therapeutic application of yoga enables participants to move slowly and safely, concentrating on relaxing their body while building flexibility, strength, and balance, which is especially important in breast cancer patients who may face additional barriers to more vigorous physical activity.31 As emotional stress has been associated with decreased survival in breast cancer patients,32 possibly by muting immune functions and accelerating the inflammatory response, stress management may offer a real survival advantage to cancer patients in addition to emotional benefits.

The STEP program’s stress management specialist is a certified yoga therapist trained in techniques to provide participants with healthier ways to deal with the stress of living with a potentially life-threatening disease. The practice of yoga relies on physical postures to stretch muscles, focused breathing and meditation to minimize stress through visualization techniques, and guided imagery. Throughout the initial intervention, stress management sessions are held once a week. During these sessions, participants receive education and training in performing these techniques. The result is a relaxed body and a peaceful state of mind. Daily stress management practice was encouraged in the STEP program so that these techniques would be routine when patients are faced with a stressful situation.

MIND/BODY HEALTH

Women with breast cancer often exhibit emotional distress similar to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).33,34 In a recent study, among women who were recruited an average of 47 months following diagnosis of breast cancer, 38% had moderate to high anxiety, 22% had moderate to high depression, and PTSD was observed in 12%.35 These findings show that the emotional impact of breast cancer can last for years following diagnosis. In addition, women lacking a social network had a significantly higher risk of breast cancer mortality than women with strong social ties to relatives, friends, and neighbors. Breast cancer patients often experience social isolation due to treatment, body image issues, or fatigue, which can have significant detrimental effects on psychological well-being by increasing levels of anxiety and depression. Therefore, it is important to recognize the signs of psychological distress in breast cancer patients and develop programs that effectively manage stress and mental health.36

The mind/body sessions in the STEP program are facilitated by a licensed therapist. These sessions are designed to create an atmosphere in which participants feel comfortable expressing their feelings and personal experiences. Since all STEP participants share common ground, individuals who self-disclose their experiences in dealing with breast disease encourage other participants to share their experiences as well. The overall purpose of the mind/body session is to create an environment where participants can experience belonging and the feeling of being connected. It is important to understand that these sessions are not group therapy – they are intended to facilitate making and sustaining healthy behaviors every day. Most of us know what we need to do to lead healthier lifestyles, but change is difficult to attain and sustain without ongoing support. This component upholds accountability, and the participants come to depend on each other for ongoing support.

CONCLUSION

In summary, lifestyle change interventions have proven to be beneficial to the vast majority of participants, but there are a limited number of studies that have examined the effect of combining several lifestyle behaviors into one comprehensive program to benefit breast cancer patients. The STEP program is a pioneer program that has combined the efforts of conventional treatment regimens with simple lifestyle changes, empowering breast cancer patients to actively manage their disease. As well-powered randomized controlled trials continue to define the effectiveness of lifestyle modification, hopefully more comprehensive programs will become available and eventually translate into improved care for breast cancer patients.

Acknowledgments

The STEP program at Windber Medical Center is a joint effort of many investigators and staff members whose contributions are gratefully acknowledged. We especially thank the program participants. This program is supported by the US Department of Defense through the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine Initiative (Military Molecular Medicine Initiative MDA W81XWH-05- 2-0075). The opinions and assertions expressed herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as reflecting the views of the Department of the Army or the Department of Defense.

Disclosures

Amy M. Burke, RN, BSN, has nothing to disclose. Darrell L. Ellsworth, PhD, has nothing to disclose. Col (Ret) Marina N. Vernalis, DO, FACC, receives funding through the Henry Jackson Foundation for her work on the Integrative Cardiac Health Project at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center.

REFERENCES

- Linden W, Stossel C, Maurice J. Psychosocial interventions for patients with coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:745-752.

- Dusseldorp E, van Elderen T, Maes S, et al. A meta-analysis of psychoeducational programs for coronary heart disease patients. Health Psychol. 1999;18:506-519.

- Nicholson A, Fuhrer R, Marmot M. Psychological distress as a predictor of CHD events in men: the effect of persistence and components of risk. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:522-530.

- Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2009-2010. American Cancer Society Web site. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@nho/documents/document/f861009final90809pdf.pdf. Accessed January 25, 2012.

- Chlebowski RT, Blackurn GL, Thomson CA, et al. Dietary fat reduction and breast cancer outcome: interim efficacy results from the Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1767-1776.

- Holmes MD, Chen WY, Feskanich D, et al. Physical activity and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. JAMA. 2005; 293:2479-2486.

- Holick CN, Newcomb PA, Trentham-Dietz A, et al. Physical activity and survival after diagnosis of invasive breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:379-386.

- Osborn RL, Demoncada AC, Feuerstein M. Psychosocial interventions for depression, anxiety, and quality of life in cancer survivors: meta-analyses. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2006;36:13-34.

- Tatrow K, Montgomery GH. Cognitive behavioral therapy techniques for distress and pain in breast cancer patients: a meta-analysis. J Behav Med. 2006;29:17-27.

- Zimmermann T, Heinrichs N, Baucom DH. “Does one size fit all?” moderators in psychosocial interventions for breast cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2007;34:225-239.

- Duijts SF, Faber MM, Oldenburg HS, et al. Effectiveness of behavioral techniques and physical exercise on psychosocial functioning and health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients and survivors—a meta-analysis. Psychooncology. 2011;20:115-126.

- Palmieri C, MacGregor T, Girgis S, et al. Serum 25-hy - droxyvitamin D levels in early and advanced breast cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59:1334-1336.

- Carney WP, Neumann R, Lipton A, et al. Monitoring the circulating levels of the HER2/neu oncoprotein in breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2004;5:105-116.

- Carney WP, Neumann R, Lipton A, et al. Potential clinical utility of serum HER2/neu oncoprotein concentrations in patients with breast cancer. Clin Chem. 2003;49:1579-1598.

- Weyandt J, Ellsworth RE, Hooke JA, et al. Environmental chemicals and breast cancer risk—a structural chemistry perspective. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:2680-2701.

- Rydstedt LW, Cropley M, Devereux J. Long-term impact of role stress and cognitive rumination upon morning and evening saliva cortisol secretion. Ergonomics. 2011;54:430-435.

- Andersen BL, Yang HC, Farrar WB, et al. Psychologic intervention improves survival for breast cancer patients: a randomized clinical trial. Cancer. 2008;113:3450-3458.

- Salas-Salvadó J, Bulló M, Babio N, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with the Mediterranean diet: results of the PREDIMED-Reus nutrition intervention randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:14-19.

- Sofi F, Cesari F, Abbate R, et al. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and health status: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;337:a1344.

- Pierce JP, Stefanick ML, Flatt SW, et al. Greater survival after breast cancer in physically active women with high vegetable-fruit intake regardless of obesity. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25: 2345-2351.

- Majed B, Moreau T, Senouci K, et al. Is obesity an independent prognosis factor in woman breast cancer? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;111:329-342.

- Demark-Wahnefried Winer EP, Rimer BK. Why women gain weight with adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:1418-1429.

- Pierce JP, Natarajan L, Cann, BJ, et al. Influence of a diet very high in vegetables, fruit, and fiber and low in fat on prognosis following treatment for breast cancer: the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) randomized trial. JAMA. 2007;298:289-298.

- Heidemann C, Schulze MB, Franco OH, et al. Dietary patterns and risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all causes in a prospective cohort of women. Circulation. 2008;118:230-237.

- Friedenreich CM, Cust AE. Physical activity and breast cancer risk: impact of timing, type and dose of activity and population subgroup effects. Br J Sports Med. 2008;42:636-647.

- Zoeller RF Jr. Lifestyle in the prevention and management of cancer: physical activity. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2009;3:353-361.

- Kruk J. Physical activity and health. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2009;10:721-728.

- Blank SE, Kittel J, Haberman MR. Active practice of Iyengar yoga as an intervention for breast cancer survivors. Int J Yoga Therapy. 2005;15:51-59.

- Lin KY, Hu YT, Chang KJ, et al. Effects of yoga on psychological health, quality of life, and physical health of patients with cancer: a meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011. doi:10.1155/2011/659876.