Patient navigation emerged 2 decades ago, with numerous articles reporting cancer care outcomes from the patient perspective, but its effect on improving organizational outcomes requires further research.1 However, according to data from the Oncology Roundtable’s Member Survey,2 almost 90% of cancer programs employ at least 1 full-time equivalent navigator, and many employ more than one.

Patient navigation incurs an initial economic burden from (1) fixed costs: program development, policies, procedures, office space and furnishings, and patient materials; (2) indirect costs: telecommunication, data collection and processing, program expenses related to patient-assistance activities, electronic forwarding of medical records, copies of imaging studies provided in a transportable format; and (3) human resources: employment (volunteer vs paid employee, clinical navigator vs lay navigator, full-time vs part-time navigation), training (at orientation and continuing education), and supervisory/administrative costs.3 Patient navigation also involves direct medical costs (patient charges that can be tracked through billing for prevention, screening, diagnostics, treatment, survivorship, and surveillance care); nonmedical costs such as transportation and help with childcare; and indirect costs attributable to mortality/morbidity and loss of job or reduced work productivity by the patient, friends, and/or family.3

Before 2010, the primary motivations for employing navigators were to enhance patient service, remove barriers to care, and improve care coordination. However, in 2010, the Commission on Cancer codified the importance of navigation by adding the provision of navigation services to its standards for cancer program accreditation, Standard 3.1: “A patient navigation process, driven by a community needs assessment, is established addressing health care disparities and barriers to care for patients. Resources to address identified barriers may be provided either on site or by referral to community-based or national organizations.”4 As a result, interest and investment in this service are expected to grow.

Achieving patient-centered, high-quality cancer care is difficult to justify when time and money are required for services that are not directly reimbursable.5 Common programmatic errors include utilizing navigators to band-aid ineffective processes, hiring staff without clearly defining organizational needs, and not having an identified system to track navigation revenue related to navigation services.2 The Patient-Reported Outcomes Working Group convened by the American Cancer Society’s National Patient Navigator Leadership Summit defined core measures to guide research and programmatic evaluation. Demonstrating significant economic and clinical values is necessary to advance patient navigation programs.3

One of the most challenging aspects of managing a navigation program is designing a method for measuring the impact of navigation services. The metrics most commonly used to monitor navigation include the number of patients receiving navigation services, overall patient satisfaction scores, and timeliness of care indicators. While each of these measures is potentially useful, none speaks to the unique value that navigators add; rather, all of them measure aspects of patient care.2 Having clearly defined goals and a measure of baseline performance for each key metric would be ideal. Selecting the appropriate measures can be difficult but must be completed and refined before starting the process of collecting data.

What is Important to Patients?

- An integrative and compassionate approach

- A relationship of trust; knowing that someone they trust will carry them throughout this journey

- Access to care in an efficient time frame

- Appropriate referral networks, including appropriate referral pathways

- Coordination of services throughout the continuum of care

- Assistance with obtaining medical records

- Individualized prescreening for potential clinical trials

- Coordination of all appointments, eg, radiation, chemotherapy

- Education that is relevant to their disease processes/treatments

- Individual support for their family members

- Access to additional services, including nutritional counseling, psychosocial counseling, complementary medicine, and educational and nursing care services, and assistance in working with community organizations

Patients and families tell us countless times how much the patient navigator helped. We, as navigators, help maintain the patient’s sense of control during a very stressful time by providing information, paving the way with appointment scheduling, answering questions that our patients may have, and providing a consistent point of contact for our patients throughout their cancer treatment and afterwards.

However, as care providers, we are also responsible for frequently evaluating our care programs using objective outcome metrics. Taking a targeted approach is important to definitively proving the value of the navigation program. By completing these evaluations, we not only make informed decisions regarding program design but we also can provide our administration with the objective data needed to support us.

Measuring Outcomes of Programmatic Success

When choosing the data to prove a point, also look at the literature and speak to administrators at your institution. Using terms or measures that the healthcare industry can understand will make your job easier. Validating your data is important, as this will help build a program that your patients, your institution, accreditation bodies, and insurance providers will value. Simplify the data collection to look at 1 or 2 prenavigation and postnavigation program data points. Each one selected should, on its own, prove beyond a doubt that the navigation program is responsible for the improvement.

Questions to Pose When Choosing Outcome Metrics

When meeting the needs of the patient, will my work increase patient volume and/or revenue at the hospital?

- Limit the use of satisfaction surveys to navigator-specific patient satisfaction tools and use data from the survey not only to assess patient satisfaction but also to identify opportunities to refine your navigation program.

- When analyzing how your patient navigation program will increase revenue for the hospital:

- Measure out-migration of patients by including a question on your baseline survey and all current program surveys. Many patients leave the system to seek second opinions because they do not have a person who will assist with making a decision or while navigating through the many treatments and procedures, thus making a difference in the patient experience. Responses that differ from the presence of a navigation program will help you elucidate that factor.

- Do not track the distance from the patient’s residence to the facility (patients vary greatly in their willingness to travel for care, and these data are not easily translatable to different regions of the country).

- Do not simply track referral patterns for all referring physicians (who have relationships or preconceptions that you alone cannot overcome). However, getting physician support is crucial for the success of the navigation program and to measure patient satisfaction with and without a navigation program.

- Do not track the number of specific procedures performed regardless of stage of cancer or patient preference (which might prove to be stronger factors than navigation alone).

How can maintaining the confidentiality of patient and provider feedback contribute to the success of the program?

- Maintaining confidentiality is especially important when using patient or staff satisfaction surveys but should also be considered during focus or support groups. Constructive criticism is needed but will be gained only when those asked feel safe in sharing their opinions.

Will this measure prove that the program improves treatment outcomes?

- Select measures that demonstrate improved outcomes through evidence-based care (better yet, can you provide the new benchmark or standard of care?). This information can be used both for marketing campaigns and in negotiating contracts for care.

- Be sure to keep the data you measure simple; the more complex the data, the greater the opportunity for confounding variables. Measuring the use of 1 treatment for a specific stage of cancer is better than looking at general outcomes for all patients with that type of cancer.

After refining what you want to measure for each specific question, thinking of your completed data as being able to tell a story that combines patients’ psychosocial and medical needs with the needs of the institution and/or care providers is helpful. Choose measures that are different from one another, and you will be sure to have a story to tell rather than a lecture on 1 aspect of care that might not interest everyone in your audience.

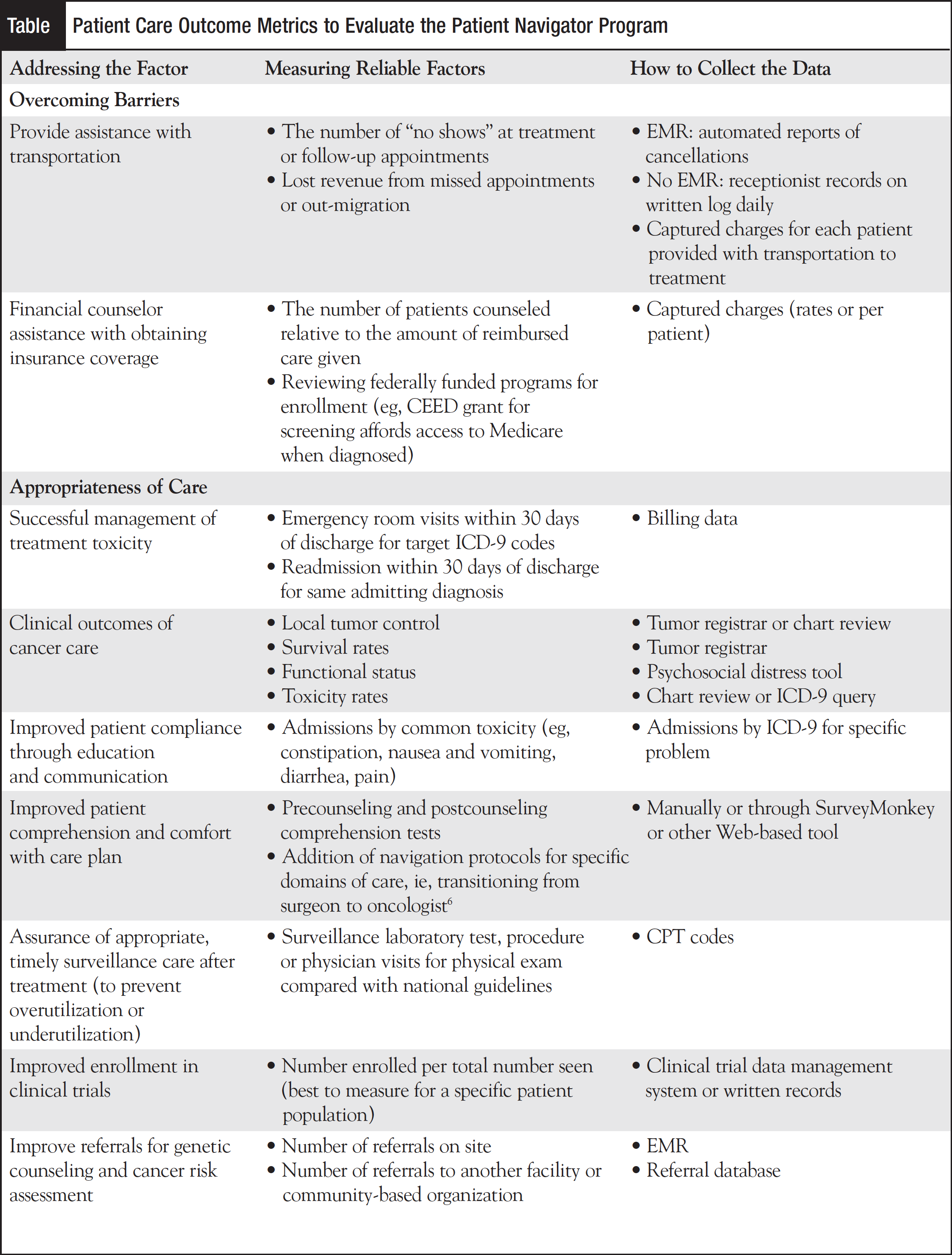

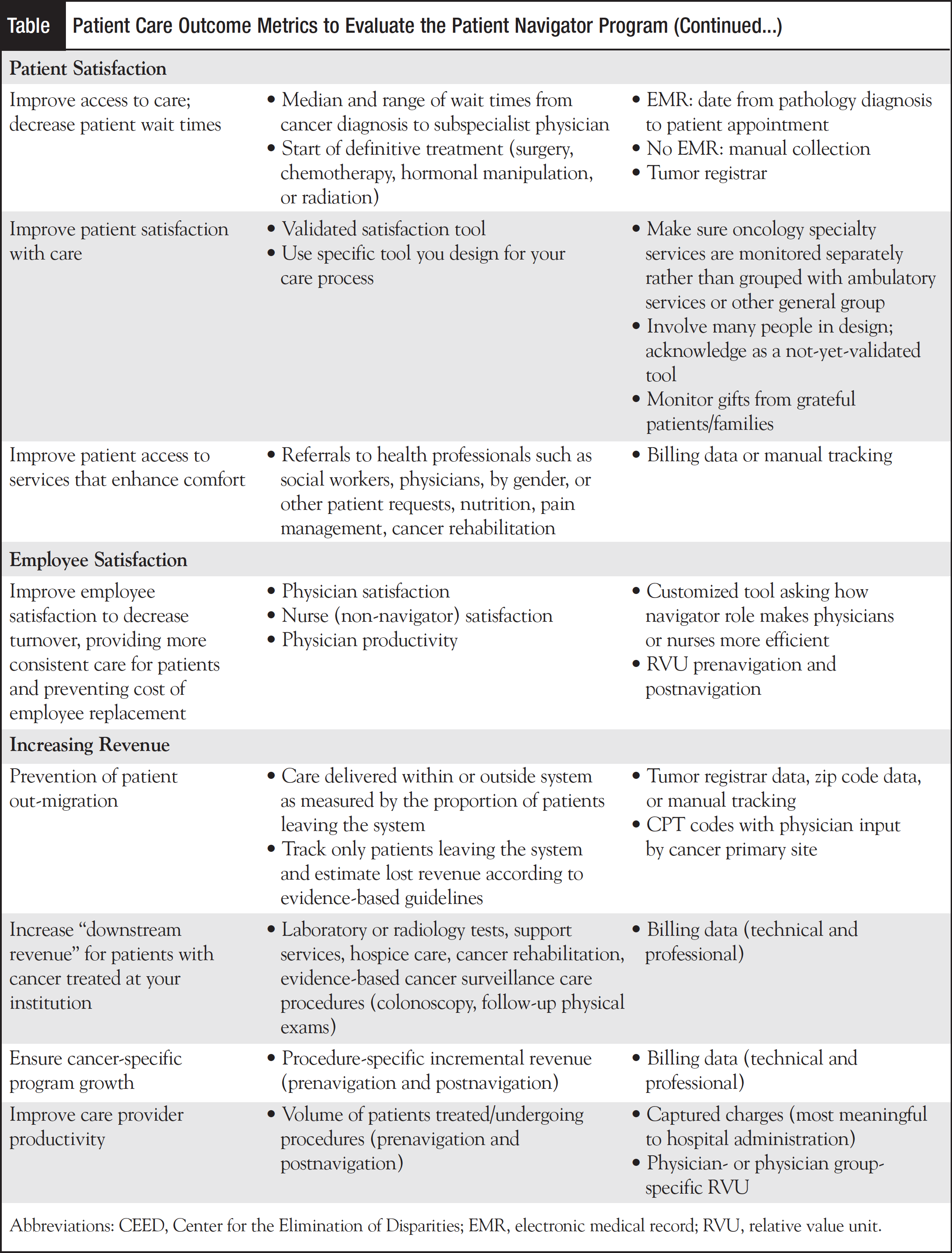

Last February, Mindstream Education held a meeting in Orlando during which the panelists and the audience came up with several measures and metrics to validate the benefits of patient navigation. Several general themes evolved with suggestions on how to monitor the collected data. The Table shows how the data should be collected, as a baseline before the navigation program exists or before any proposed enhancements, and then reported on a schedule that most relates to the urgency of the problem.

Being diagnosed with cancer can be devastating because patients worry about the unknown and what the future may hold for them. Cancer patients are compromised initially with the burden of a cancer diagnosis, and their coordination of care is yet another unnecessary stressor. Family caregivers for cancer patients experience high levels of stress and burden and diminished quality of life. Ongoing research in the search for a cure has resulted in increased treatment options and multiple modalities; consequently, the coordination of treatments and services has become extensive and complex for patients and their families. In addition, exploring the best treatment options, such as clinical trials, procedures, and new drugs, without guidance can become cumbersome and overwhelming. Inadvertently, this causes delays in access to care, diagnosis, education, and treatment. How can a nurse navigator help? He or she can help by moving the patient smoothly through the healthcare system during the continuum of care.

As patient navigation services evolve and expand, nurses and social workers in oncology have roles in educating patients, survivors, families, healthcare teams and systems, and the public about patient navigation. Challenges revolve around measuring and ensuring desired and optimal outcomes for patients, families, survivors, and individuals in patient navigator roles and processes to address sustainability of navigation programs and services.7

Disclosures: Ana Rosa Espinosa, DNP, MBA, RN, OCN, has no conflict of interest or financial interest to disclose. Molly Gabel, MD, has no conflict of interest or financial interest to disclose. Pamela Vlahakis, RN, MSN, CBCN, has no conflict of interest or financial interest to disclose.

References

- Paskett EH, Harrop JP, Wells KJ. Patient navigation: an update on the state of the science. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;41:237-249.

- Oncology Roundtable. Maximizing the value of patient navigation. The Advisory Board Company Web site. http://www.advisory.com/Research/Oncology-Roundtable/Studies/2011/Maximizing-the-Value-of-Patient-Navigation. Accessed September 25, 2012.

- Whitley E, Valverde P, Wells K, et al. Establishing common cost measures to evaluate the economic value of patient navigation programs. Cancer. 2011;117(15 suppl):3618-3625.

- American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer. Cancer Program Standards 2012: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2011.

- Delivering on the promise of patient-centered care: designing services to support the whole patient. The Advisory Board Company Web site. http://www.advisory.com/Research/Oncology-Roundtable/Studies/2011/Delivering-on-the-Promise-of-Patient-Centered-Care. Accessed October 6, 2012.

- Pedersen A, Hack TF. Pilots of oncology health care: a concept analysis of the patient navigator role. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37(1):55-60.

- Wells KJ, Battaglia TA, Dudley DJ, et al. Patient navigation: state of the art or is it science? Cancer. 2008;113(8):1999-2010.