Memphis, TN—On Sunday, November 17, 2013, a series of breakout sessions were conducted to highlight navigation challenges in the context of specific tumor types. Experts in the development of navigation programs and services for patients with breast cancer, colorectal cancer, gynecologic cancer, pediatric oncology, and others shared their experiences and advice.

The breakout session on thoracic oncology navigation, titled “Lung Cancer Screening: Where Are We Now?” was led by Gean Brown, RN, OCN. Ms Brown is the Clinical Manager and Lung Screening Coordinator at the Middlesex Hospital Cancer Center in Middletown, Connecticut. She oversees the cancer center’s oncology nurse navigators, as well as the surgical alliance. Ms Brown also held several board positions in Central Connecticut’s Oncology Nursing Society, and is a member of the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators (AONN+).

Ms Brown began by acknowledging the value of AONN+’s annual meetings. She recalled being inspired to initiate a lung cancer screening program at her community-based hospital after hearing a past AONN+ lecture. “This is my fourth year coming here; I love this conference!”

The breakout session on lung cancer screening had 4 objectives:

- Describe the National Lung Screening Trial and its screening criteria

- Outline a standardized approach to implementing a lung screening program

- Identify sources of lung nodule management guidelines

- Define the role of the navigator in lung cancer screening.

Before addressing these topics, Ms Brown reminded navigators in her session that lung cancer accounts for 30% of deaths from cancer in the United States; its 5-year survival rate is only 15%. Because half of the adults in the United States have a smoking history, they remain at higher risk for lung cancer even if they quit.

The Value of Lung Cancer Screening

Ms Brown then reviewed groundbreaking studies of lung cancer screening. From 2002 through 2004, the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) conducted a study comparing 2 ways of detecting lung cancer: low-dose helical computed tomography (CT) and standard chest x-ray.1 More than 53,000 people between 55 and 74 years of age with a smoking history of at least 30 pack-years were randomized to be screened using one of those methods.1 The investigators determined that patients who received low-dose helical CT scans had a 20% lower mortality risk from lung cancer compared with patients who received standard chest x-rays. Published in 2010, and updated in 2013, this decade-long study established low-dose helical CT as the first validated screening test that can reduce mortality due to lung cancer, according to Ms Brown.

The American Lung Association has estimated that 7 million of the 94 million current and former smokers in the United States fit the high-risk demographic criteria used in the NLST. The American Cancer Society believes that approximately 8.6 million smokers meet the criteria. Consequently, the NLST reported that screening could potentially avert up to 12,000 or 7.6% of total lung cancer deaths reported each year.

Citing another large screening study, the International Early Lung Cancer Action Project (I-ELCAP), Ms Brown states that 85% of 484 lung cancers detected by CT scan were stage I or highly treatable. These patients have an expected 10-year survival of approximately 88%. Ms Brown recalled that critics of the I-ELCAP study highlight the lack of randomization (ie, all patients received CT scans). However, based on this study, it is generally accepted that CT screening facilitates detection of lung cancer at its earliest, most curable stage, Ms Brown explained.

Based on these 2 large research efforts, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) published a recommendation for lung cancer screening in July 2013. Screening is recommended for current and former smokers aged 55 to 80 years with a smoking history equivalent to a pack a day for 30 years or 2 packs a day for 15 years.2

Because the USPSTF recommendation was given a “B” rating, insurers must reimburse CT scans as a free preventive service to patients according to the Affordable Care Act. Ms Brown highlighted data from an actuarial analysis published in April 2012. This analysis documented that the cost per life-year saved with lung cancer screening is less than $19,000, which compares favorably with screening for cervical, breast, and colorectal cancers.

By enhancing access to lung cancer screening, these data and the USPSTF recommendation can significantly enhance outcomes and care for lung cancer patients. To underscore the importance of this national recommendation, Ms Brown quoted Laurie Fenton Ambrose, leader of an advocacy group known as the Lung Cancer Alliance: “Tens of thousands of lives could be saved. Screening those at high risk…will open the door to much faster advances in research on all stages of lung cancer. This is a game changer.”

Steps in Developing a Lung Cancer Screening Program

“Lung cancer screening is a clinical diagnostic process, not just 1 test,” Ms Brown stated, prefacing her discussion of hospital-based lung cancer screening programs by highlighting the importance of developing a comprehensive effort. “If you find a nodule, you have to follow it. You need a tracking system. You need physicians to whom you can refer patients. It is a whole system.”

Starting a lung cancer screening program should include the following steps:

- Define patient selection criteria

- Identify equipment and define protocol for low-dose CT scanning

- Determine whether patients will need a referral or physician order for screening

- Determine whether patients will be charged for screening

- Develop patient-tracking and follow-up systems

- Develop and implement a smoking cessation effort

- Build a multidisciplinary team: administration, navigator, radiology, thoracic surgery, pulmonary, medical oncology, radiation oncology, marketing

- Develop a data collection system to track the program’s outcomes.

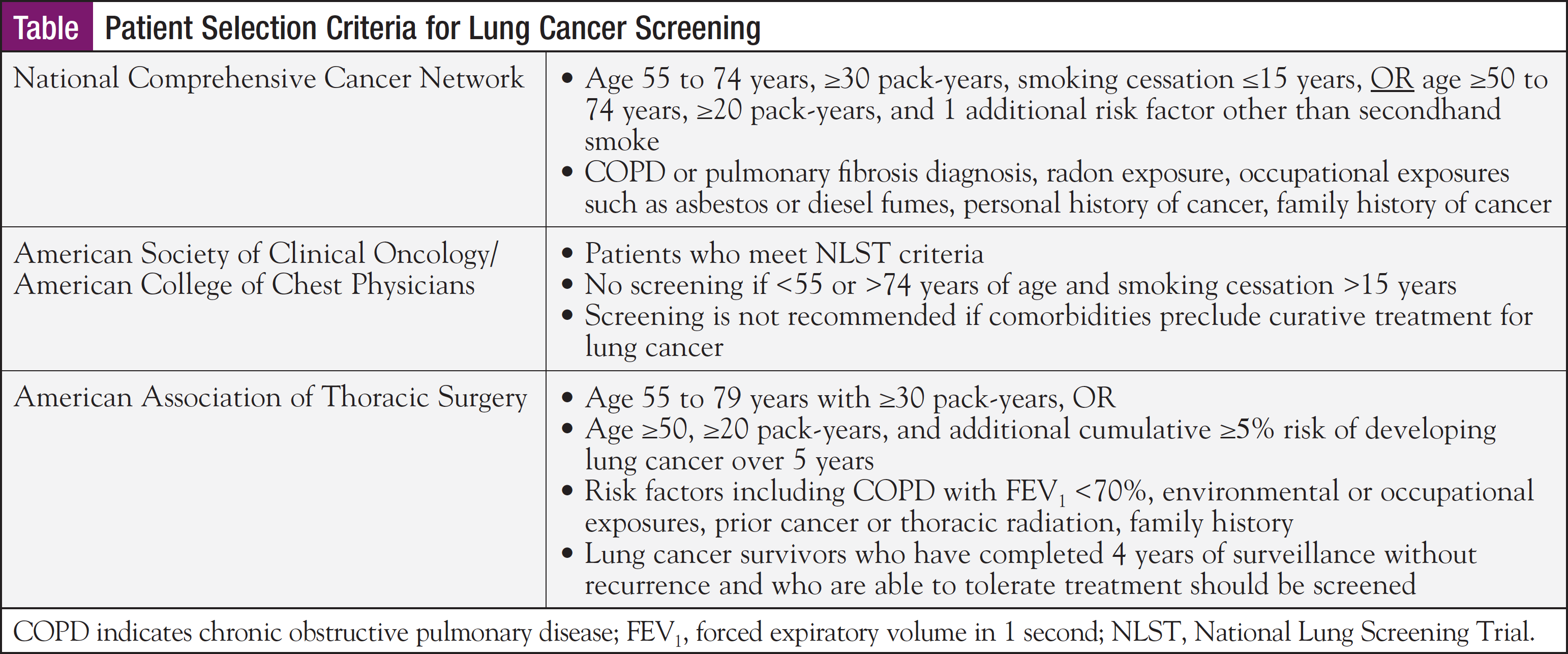

Ms Brown summarized 3 sets of lung cancer screening guidelines that have been adopted by expert groups (Table). She noted that her community hospital in Connecticut currently uses National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for patient selection. She predicted, however, that the NCCN criteria—and those of the American Society of Clinical Oncology/American College of Chest Physicians—are likely to expand and encompass people who have ceased smoking more than 15 years prior to screening.

When discussing equipment and imaging protocols, Ms Brown described that, because it uses thinner images and detects small lung nodules, helical multidetector CT of the chest is recommended. While there is no strict definition of “low-dose” CT, 10% to 30% of standard-dose CT is typically used.

In the lung cancer screening program she is affiliated with, patients are required to have a physician’s order, typically from a primary care physician. In other cancer centers, such as the Lahey Clinic in Boston, radiologists initially evaluate patients and then order low-dose helical CT scans, Ms Brown noted. The Lung Cancer Alliance recommends that lung screening CTs are read by trained radiologists to ensure that lung nodules are identified accurately.

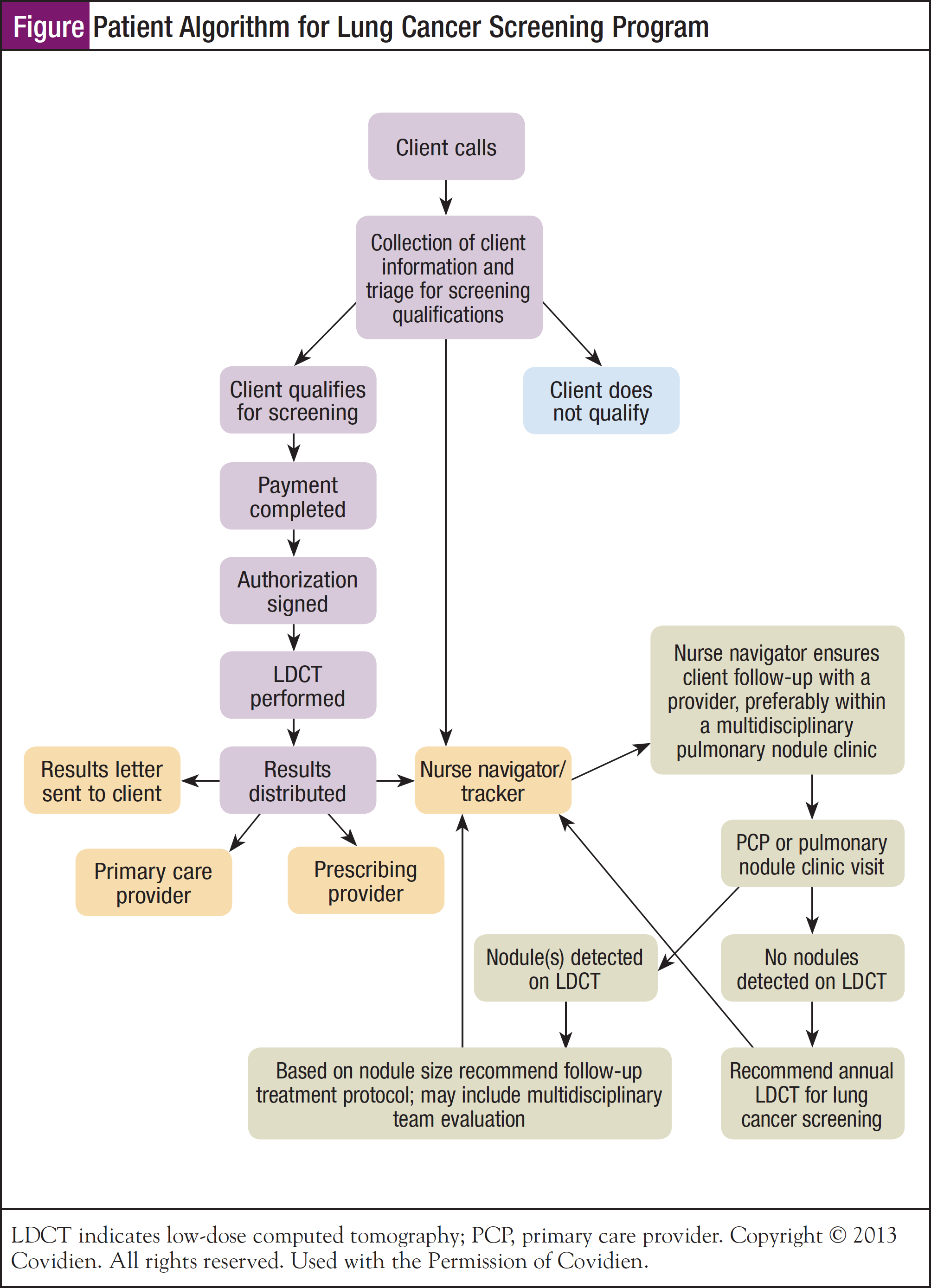

Patient follow-up is a critical component of successful lung cancer screening programs. A formal system, either electronic or paper-based, must be developed to ensure patients are not lost to follow-up. For example, high-risk patients whose CT scans are negative should be scanned again in 1 year; a process must be in place to remind them. To this end, Ms Brown shared an algorithm that has been developed by Covidien that lists specific decision points, as well as steps involved in patient screening and follow-up (Figure).

“Navigator is the most important part of the team,” Ms Brown noted. “In our hospital, the nurse navigator is the one who coordinates the lung screening program, collects data, and ensures that patients are followed.”

Marketing a new lung cancer screening program is a very important component. Local and regional efforts should target physicians and other healthcare providers, as well as patients and advocacy organizations, with information about the screening program and its benefits. Brochures, websites, and other communications are valuable for explaining the program and its importance.

Debates in Lung Cancer Screening

Similar to mammography and prostate-specific antigen screening, lung cancer screening has the potential to be both beneficial and harmful. A screening effort is effective only when its benefits outweigh harms. In lung cancer screening, false-positive results can lead to unnecessary biopsies and surgery. However, research also demonstrates that screening saves lives by detecting resectable early-stage lung cancers.

“Clearly, any screening program needs to balance lowering the frequency for positive results with the resulting delay in the diagnosis of lung cancer, which in some cases, may lead to stage progression and thus a decrease in curability,” Ms Brown stated, quoting Claudia Henschke, MD, of Mount Sinai Medical Center, an investigator in I-ELCAP.

When discussing false positives in lung cancer screening, Ms Brown noted that different thresholds for lung nodule size have been proffered. For example, I-ELCAP uses a nodule diameter of 5 mm (any nodule smaller than 5 mm is considered negative), while the NLST uses a threshold of 4 mm. Because of improved imaging, chances of finding small nodules (ie, false positives) with CT screening are increasing. Experts debate the appropriate criterion and many predict it will change.

Ms Brown also suggested that identification of a small lung nodule should not be interpreted as a false positive at all; this terminology may be inappropriate. “Small nodules are not necessarily false positives. It is still a nodule. It might not be lung cancer, but still, something needs to be done. It could be something else. Calling it a false positive seems wrong to me.”

To address risks associated with lung cancer screening, organizations that have published screening guidelines have also documented the rate of false-positive results. These organizations strongly emphasize the importance of informed decision-making by patients, reinforcing the importance of navigators in counseling these patients and their families, Ms Brown noted.

A second area of debate relates to patient follow-up after screening. The original I-ELCAP study included 3 annual screenings, she explained. If the first lung screening is negative, then a second is performed 1 year later. If the second screening is negative, another scan is performed the following year. If this one was negative, no further screening was recommended. Many experts, however, suggest that screening for these high-risk patients should continue indefinitely, according to Ms Brown.

Approximately 5% of patients who have had a negative baseline result developed a lung nodule 1 year later, stated Ms Brown. In addition, she noted that most screened patients have 1 risk factor for lung cancer, such as family history and/or lung disease. Ms Brown reminded navigators that those risk factors do not “go away” after 3 years. At this time, NCCN screening guidelines state that consensus has not been reached regarding when or if screening should cease for high-risk individuals.3

Lung Cancer Screening Data Collection

Data collection is critical for justifying the program’s clinical and financial value. Ms Brown outlined several key statistics that should be collected and documented each month:

- CT screenings performed

- Number of lung nodules identified

- Number of biopsies performed

- Number of cancers identified

- Patients’ current smoking status

- Smoking cessation program enrollment

- Patient referral sources

- Downstream revenue: biopsies, CT scans, physician visits, smoking cessation programs.

When discussing hospital revenue, Ms Brown provided statistics related to patients participating in her community hospital’s program: A patient who required lung cancer surgery to remove a stage IA nodule generated over $60,000 in revenue from April 2012 through November 2013. Another surveillance patient—one in whom no nodules have been found—generated over $13,000 from May 2012 to November 2013 for follow-up CT scans. Hospital administration often focuses on data like these to justify program funding.

Lung Cancer Screening Program Information and Software Resources

Navigators can find additional information and tools regarding lung cancer screening at the following websites:

- International Early Lung and Cardiac Action Program (I-ELCAP): www.ielcap.org

- Lung Cancer Alliance: www.lungcanceralliance.org

- National Lung Cancer Partnership: www.freetobreathe.org

- Lahey Clinic: www.lahey.org/lungscreening

- C-Change: www.c-changetogether.org

Ms Brown concluded her presentation with a list of oncology-specific software programs that are designed to help patient and nurse navigators schedule, track, organize, and report their interactions with cancer patients:

- Oncology OnTrak: www.priorityconsult.com

- NurseNav Oncology: www.nursenav.com

- Navigation Tracker: www.navigationtracker.com

- Medical Concierge Navigator: http://healthcareoss.com/products/medical-concierge-navigator/

- OncoNav: www.onco-nav.com

After fielding questions and comments from her navigator colleagues in the audience, Ms Brown expressed her appreciation for the lung cancer screening efforts represented by the group, “This is really exciting! There are so many people doing [lung cancer screening] programs now! When I first listened to Pam Madden talk about lung screening in 2010, there was one other person in the room with a program. This is great!”

References

1. The National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Results of initial low-dose computed tomographic screening for lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013; 368(21):1980-1991.

2. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Lung Cancer. December 2013. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf13/lungcan/lungcan fact.pdf. Accessed March 24, 2014.

3. National Comprehensive Cancer Network, NCCN guidelines version 1. 2012 lung cancer screening. www.NCCN.org. Accessed March 25, 2014.