Memphis, TN—In order to ensure high-quality patient-centered healthcare, oncology navigators must know patients’ needs and understand the factors that influence whether and how those needs are met. Systematic assessment of cancer patients’ needs is integral to navigators’ role in addressing cancer patients’ needs effectively.

In recognition of this tenet, the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer (CoC) has developed Standard 3.1: “A patient navigation process, driven by a community needs assessment, is established to address health care disparities and barriers to care for patients. Resources to address identified barriers may be provided either on-site or by referral to community-based or national organizations. The navigation process is evaluated, documented, and reported to the cancer committee annually. The patient navigation process is modified or enhanced each year to address additional barriers identified by the community needs assessment.”1

To comply with CoC Standard 3.1 in 2015, navigation programs will be asked to:

- Conduct a community needs assessment (CNA) at least once during the 3-year survey cycle

- Establish a patient navigation process that provides resources to overcome barriers to cancer care. Resources can be provided to cancer patients on-site or through referral to community-based or national organizations

- Evaluate the patient navigation process each year, documenting findings and reporting these findings to the cancer committee

- Modify the patient navigation process to address newly identified barriers to care.

The CNA is the first step of the CoC process and must be documented for compliance with Standard 3.1. The Internal Revenue Service also requires nonprofit organizations with 501[c][3] designations to report details about the population served, as well as identified disparities and opportunities to fill those gaps in care.

To help attendees of the Fourth Annual Conference of the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators to better understand this process, Jennifer Klemp, PhD, MPH, MA, Associate Professor of Medicine, Division of Clinical Oncology, Director of Cancer Survivorship, University of Kansas Cancer Center, presented “Community Needs and Navigation.”

Specifically, Dr Klemp reviewed the steps in cancer-focused CNA, defining their scope and purpose, and outlining methods for CNA implementation. She also showcased examples in which the aspects of the patient navigation process were enhanced by CNA findings.

Her goal was to help navigators who are focused on meeting CoC standards, as well as those who wish to optimize patient care regardless of CoC accreditation. “Many of you are in hospital systems or organizations that are accredited by the CoC. But what if you work in a community-based practice, where meeting this accreditation standard is not part of your organization’s mission? The reality is that the CoC approach remains a benchmark for best practice.”

To set the stage, Dr Klemp defined CNA as a process designed to identify the needs of populations served with the ultimate objective of improving healthcare disparities and gaps. In the context of cancer care, “needs” relate to cancer patients’ access, education, treatment, monitoring, and psychological support.

Dr Klemp then reviewed the general steps associated with CNA, including:

- Delineate the community served (primary service area)

- Assess current cancer-related conditions and resources

- Describe desired conditions (services, resources, etc)

- Identify gaps in care, barriers to care, needs that are not being addressed, and areas to improve

- Implement programs, services, and partnerships that target identified barriers.

“You need to fully understand who is out there. What community are you serving? Who can you collaborate with? How can you establish those relationships?”

When preparing for the CNA, Dr Klemp highlighted the importance of a working group, a committee of healthcare professionals dedicated to this phase of the oncology navigation program. She described that her cancer center has designated a working group responsible for conducting and reporting the CNA. This group is also part of our cancer committee.

Navigators are uniquely qualified to take a leadership role in implementing the CNA, including identifying and recruiting members of the working group, developing a timeline of activities, and reporting findings. Given their extensive network of relationships among hospital personnel, navigators can foster idea- and information-sharing, help others appreciate the complexities of delivering care to a diverse population, and drive consensus regarding the nature of an oncology navigation program and its role in improving patient outcomes.

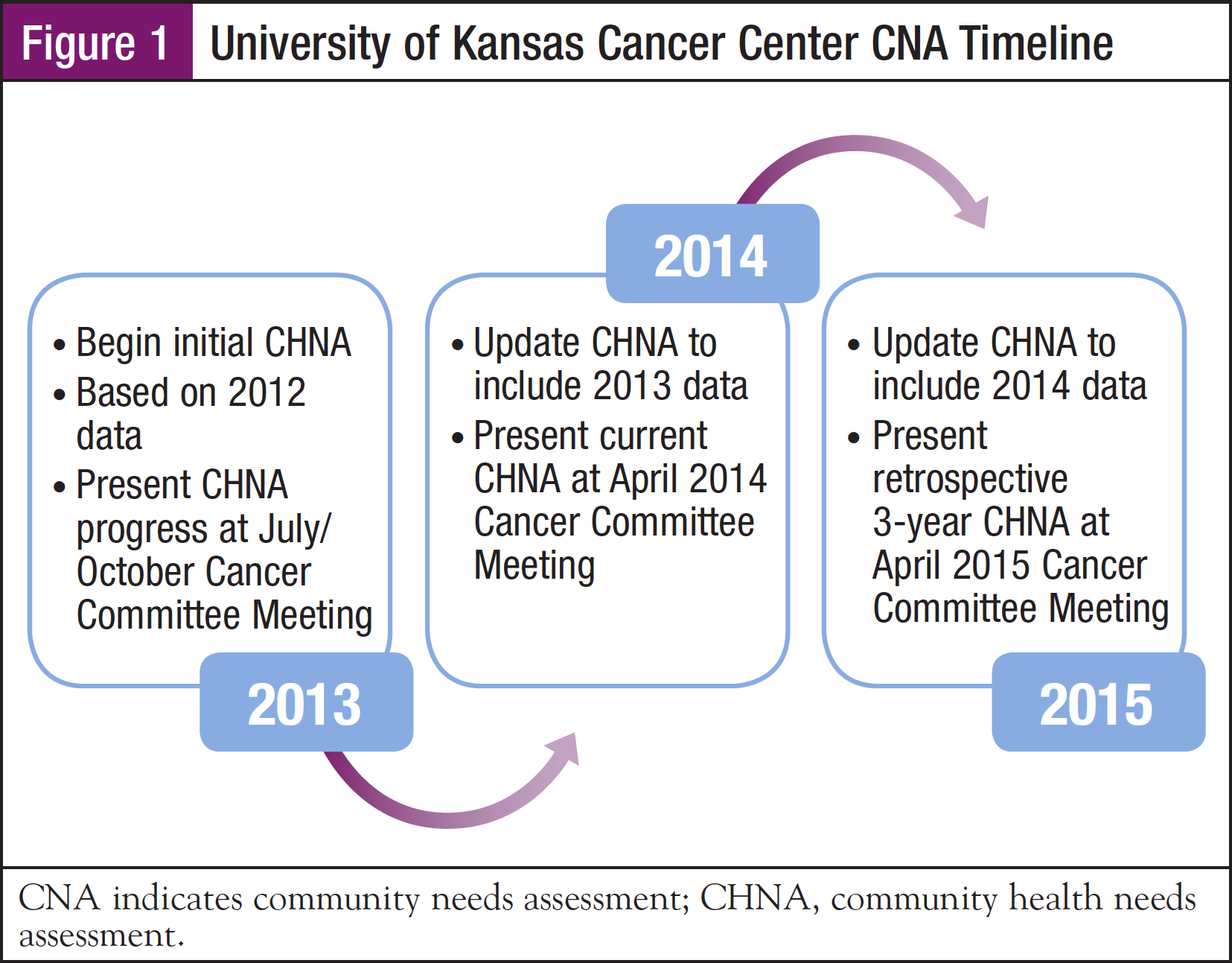

Dr Klemp reminded the audience that while some of the steps in CNA can sound easy, such as “define the community served” and “develop a realistic timeline,” they can be quite challenging. To illustrate, she shared strategies and insights from her hospital’s CNA process, including the project timeline (Figure 1). “Our CNA working group started meeting at the beginning of 2013. By including specific milestones in our cancer committee meeting agendas, we knew that we must report to the committee every quarter. As part of our timeline, we also know that we need to update the CNA every 3 years.” Dr Klemp explained that the CNA is an almost continuous process: “Trying to collect these data all at once would be very cumbersome.”

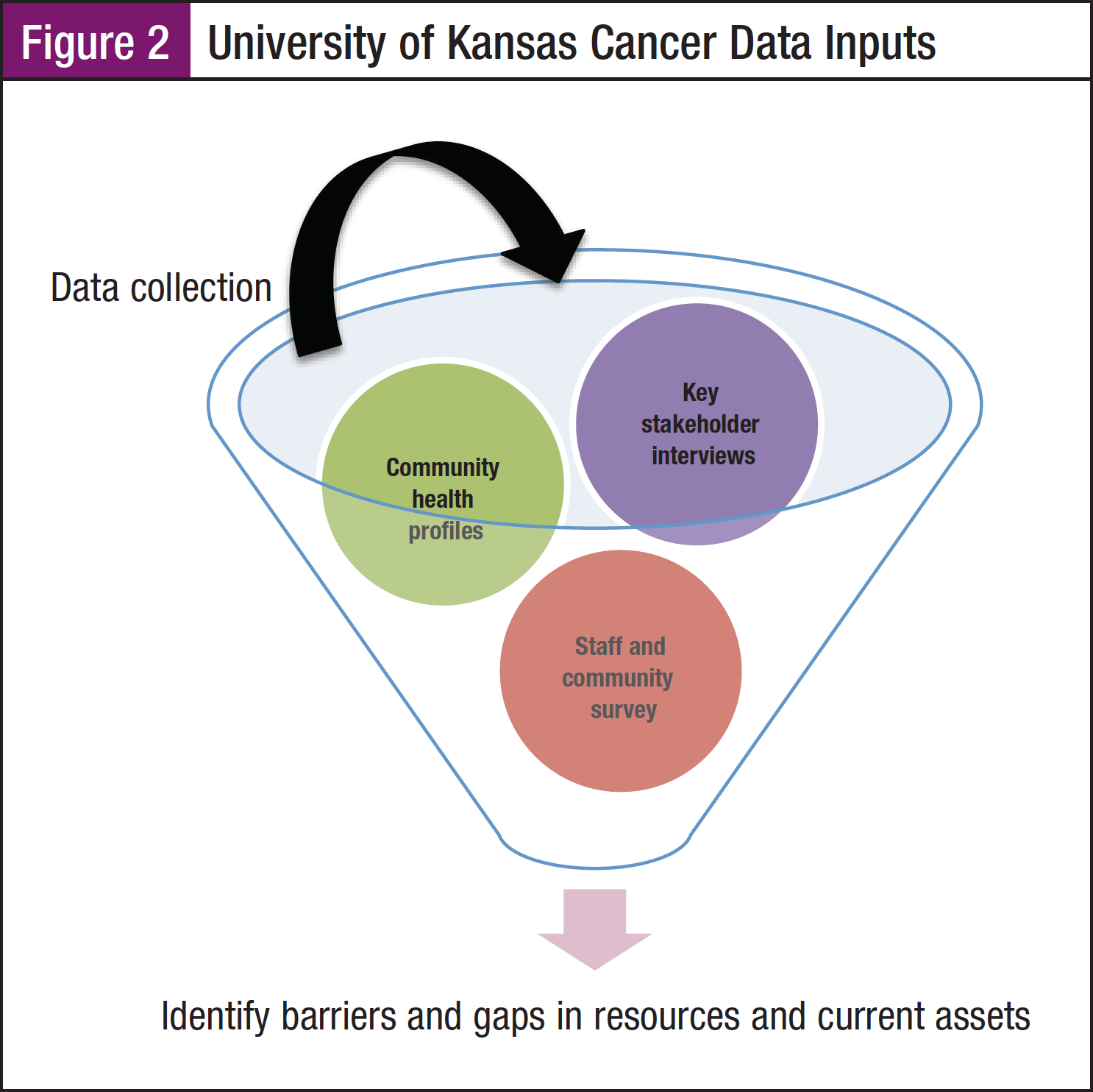

What data are important for the CNA? How do you collect these data? Dr Klemp described 3 data collection steps that she and her colleagues performed during the CNA process: (1) community health profiling, (2) a staff and community survey to identify current assets, as well as barriers and gaps in resources, and (3) key stakeholder interviews to develop and refine strategy (Figure 2). She outlined the tools that were used for this process, including written surveys and in-person interviews.

Community Health Profile

“The community health profile allows us to define our community, including the geography that we serve.” To do this, both primary and secondary data are needed. Dr Klemp explained that a key source of primary data is your hospital’s registrar. A registrar’s database can be queried to identify all analytic cases, or the current cancer population. Their data include patient demographics, diagnostic information, and their location. These data help navigators take a “snapshot” of the population served by the cancer center, including patients’ locations relative to the center’s predefined catchment area.

Using a map of the Kansas City region, Dr Klemp outlined her committee’s approach to defining their primary service area. “We cover good portions of 2 states, Kansas and Missouri, but we decided to focus our CNA in the 6 county catchment area around Kansas City. Our hospital has 8 locations in these counties, so it was important to get a representative view of those counties.” When describing her hospital’s scope, Dr Klemp also noted that the rural network includes a prevention and survivorship clinic for geographically isolated cancer patients and providers.

After the CNA working group has identified specific counties and towns as the primary service area, they can acquire and review benchmark data from national, regional, and state databases. “You can learn a lot about the particular counties in your area,” Dr Klemp advised. “There are great resources that already aggregate key data for you.” She noted the importance of considering information from the US Census Bureau, County Health Rankings, Comprehensive Cancer Control Plan, as well as the state health departments. The National Cancer Data Base, American Cancer Society, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention can also provide robust statistics regarding specific geographies in the United States.

Staff and Community Survey

The next step after defining the primary service area is to collect data regarding the nature and scope of available resources for cancer patients, as well as resource needs and gaps. Dr Klemp shared an example of a survey that she and her colleagues developed and disseminated to healthcare professionals and administrators associated with the University of Kansas Cancer Center. They chose SurveyMonkey, a web-based survey, to prepare and disseminate the survey via the Internet. To enhance the likelihood of response, the survey included only 7 questions, including the following:

- Which (University of Kansas) location is your primary workplace?

- Do you regularly refer or suggest cancer patients and/or their caregivers to any of these support services (American Cancer Society, Cancer Action, Gilda’s Club, LIVESTRONG at the YMCA, support groups, etc)?

- Do you refer or schedule cancer patients for any of the following services (cardiology, dermatology, genetic counseling, integrative medicine, etc)?

- Where do you typically send or schedule cancer patients for the following services (dietetics, fertility preservation, lymphedema education, hospice, preventive screening, psychology, etc)?

Dr Klemp highlighted the importance of listing specific services in these questions, “If they are not referring to Gilda’s Club, for example, maybe it is a teachable moment. The great part about a survey, whether it is with patients or your colleagues, is that it can be a data collection and a teaching tool at the same time.” She also focused on the importance of understanding if and how survivorship programs are functioning. “Part of the role of our survivorship program is to make sure that patient referrals are seamless. If we want our patients to be referred to cardiology, we must ensure that there is a resource in our hospital that can adequately support their care needs.”

Dr Klemp then summarized some of the results of her CNA staff survey. She indicated that the majority of the 176 survey respondents were clinical staff members, as well as administrators (such as schedulers and healthcare technicians), management, and research staff. “We wanted anyone who touches that patient. A lot of times our schedulers have some of the best relationships with our patients, because they are the ones spending time with them before and after each visit, making sure that they get their schedules and instructions.”

She showed survey results related to community support services, such as the American Cancer Society, Gilda’s Club, support groups, and others. While more than 90% of survey respondents referred cancer patients to Cancer Action, less than 30% were referred to Gilda’s Club and the LIVESTRONG program at the YMCA. Dr Klemp stated, “We cannot exist without our community resources, and we need to figure out how to best use them. Forming relationships with groups you do not currently work with and nurturing relationships with those that you do know are essential. You can use these survey data to prompt more questions: Why are we not referring to these organizations? How do we help these organizations to meet patient needs and overcome barriers to access?”

The staff survey also helped Dr Klemp and her colleagues to learn what programs were working well. “About a year ago, we started an outpatient palliative care program and we can see that those referrals have skyrocketed. These palliative care teams are at our academic center and in some of our community locations. We also have high levels of referral to our cardio-oncology program, which started in 2007. We want to keep that momentum for both acute care and screening.”

Survey results also identified gaps in services for cancer patients in the Kansas City area, including complementary and alternative medicine, as well as sexual health counseling. Community practitioners specifically requested the need for more navigation and social work support.

Dr Klemp described that many of these community practices are isolated in stand-alone facilities. They do not have the infrastructure of an academic center or hospital-based program. “We had to figure out how to build navigation and social work services into these stand-alone community practices,” Dr Klemp explained. “But we have also had to be realistic. A stand-alone community practice cannot offer the same exact services as an academic center. We are developing minimum standards for these stand-alone facilities now, knowing that the service offerings are going to evolve.”

Dr Klemp’s staff survey also indicated that, as in other regions of the country, transportation is the most significant barrier to cancer care for people in the Kansas City area. Patients must drive significant distances to see their healthcare professionals, which is highly burdensome for them and their families. “These survey data are helpful, as you can see, in our program planning. We should not take next steps without this information to guide us.”

Identify and Interview Key Stakeholders

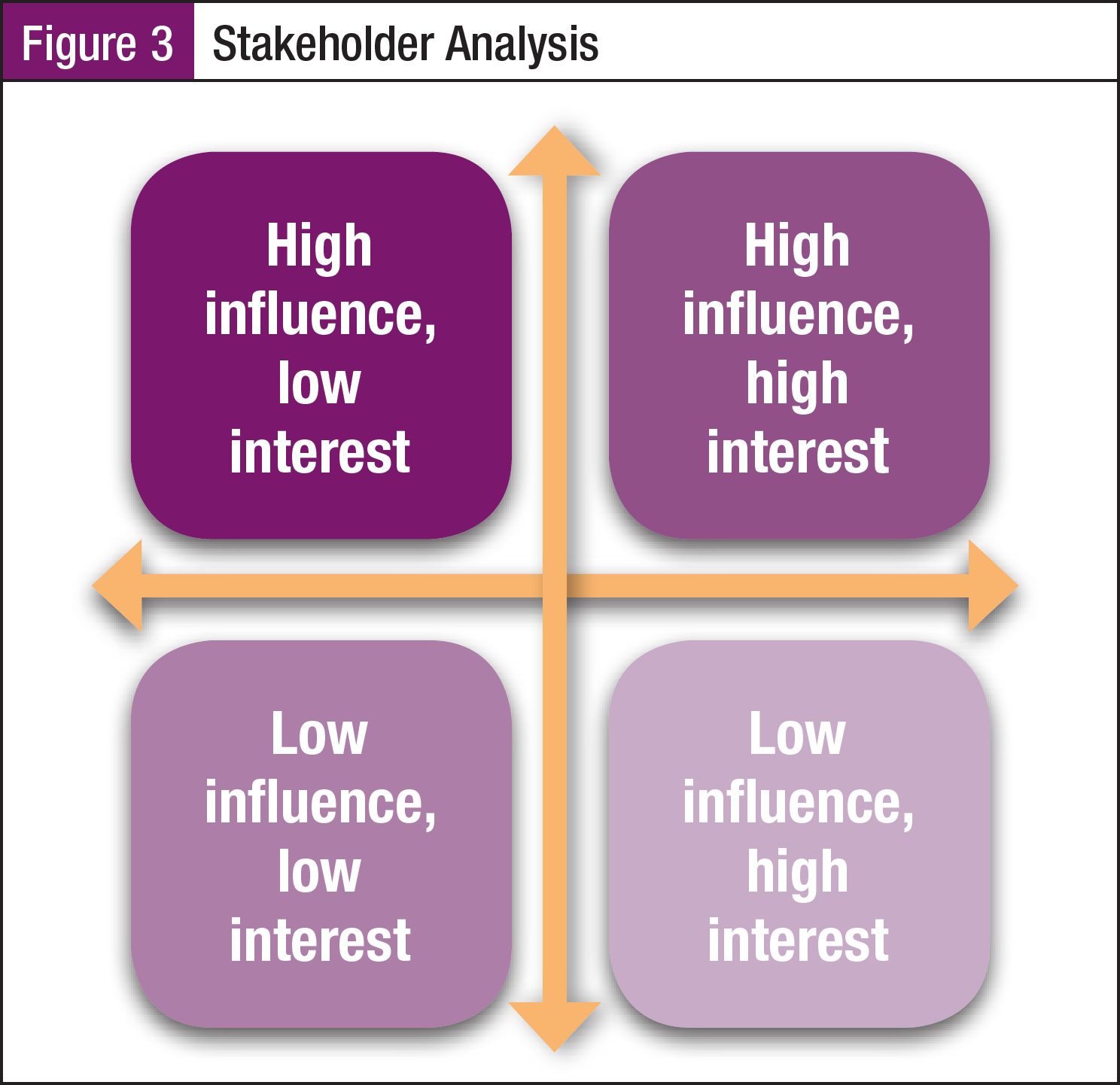

The final step in the CNA process is to interview key stakeholders, which really brings all of the other pieces together, according to Dr Klemp. She provided a diagram to help navigators categorize key stakeholders and determine their role in planning and decision-making (Figure 3). “You want to focus on individuals or organizations that have high influence (ability to impact the project) and high interest in participating in the process,” she explained. “We evaluated people’s and organization’s level of interest and influence, and then organized them in this grid. This does not mean those who have lower interest or lower influence are ignored. This just means that we focused on those who have more interest and influence.”

From key stakeholder interviews conducted to date, Dr Klemp and her colleagues have learned patient care challenges revolve around access to services and collaboration among staff members, as well as collaboration between the cancer center and the community-based organizations that provide support services. “The larger we grow, the more integrated our health systems become, the more complicated they become. This is where the navigation process is essential for helping patients into the system and helping them transition through the system.”

Dr Klemp and her CNA working group have also learned that their cancer center’s strengths include exceptional quality of care, as well as the nature and volume of support services available. These are marketable features of the center that can be leveraged in formal advertising and educational venues, as well as informal communications and conversations.

Upon completion of the CNA process, findings must be documented for the cancer committee and the CoC. The written report needs to summarize the patient population being served, list barriers to care that have been identified, and describe health disparities. It should review the navigation process, activities, and metrics that were used in the CNA, including results and outcomes, areas for quality improvement, and future plans based on the CNA.

Dr Klemp concluded by reminding navigators of their integral part in defining and evolving the patient navigation process. Navigators appreciate disparities and barriers to care, continually formulate strategies to address barriers to care, and implement quality measures for practice improvement. With today’s changing healthcare models and cost pressures, Dr Klemp asserted, “We are going to be put in a position where we are going to need to know more and contribute more to our organization. Quoting Goethe, she reminded the audience, ‘Knowing is not enough, we must apply. Willing is not enough, we must do.’ ”

Reference

- Commission on Cancer. Cancer Program Standards 2012: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care. Version 1.2. http://www.facs.org/cancer/coc/programstandards 2012.pdf. Accessed June 2, 2014.