Rehabilitation medicine for patients with cancer serves 2 fundamental roles, according to Adrian Cristian, MD, MHCM, chief, Cancer Rehabilitation at the Miami Cancer Institute. First, to maximize a person’s level of function, whether that be physical, social, psychological, or vocational, and second, to improve quality of life as defined by the individual with cancer. This includes return to work or school, family life, and hobbies. Although rehab (and prehab) can be invaluable to restoring an individual’s functioning after a cancer diagnosis, barriers to the provision of prehab and rehab services do exist. But according to Dr Cristian, navigators can play an essential role in breaking down these barriers.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined “function” as activities identified by the individual as essential to supporting physical, social, and psychological well-being. “What’s important to know here is that cancer and cancer treatment can have a significantly adverse impact on one’s level of function,” he said at the AONN+ 11th Annual Navigation & Survivorship Conference. “Functional loss in cancer is often very gradual, subtle, and slow and is sometimes hard to detect at the very early stages.”

The WHO has provided a framework for describing function and functional loss through the concepts of impairment, activity limitation, and participation restriction. Physical impairments are measured in a clinical setting (eg, muscle strength and sensory loss).

Activity limitation is defined as what a person can no longer do as a result of those physical impairments, and participation restrictions are in the context of an individual’s role in society, whether that be at work, school, or in family and social roles. Rehabilitation medicine clinicians provide expertise in identifying and treating these physical impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions.

According to Dr Cristian, the concept of oncological- functional integration is focused on maximizing and preserving the functioning of individuals going through cancer treatment throughout the entire continuum, from acute care, to home therapy, to outpatient and post-acute care. “I like to think of physical function as a vital sign that should be measured as part of clinical care,” he said.

Work and Cancer

Work is an integral part of life and is important for the good physical and mental health of an individual, but cancer and cancer treatment can have an adverse impact on a person’s ability to work. “The statistics are quite striking: only about two-thirds of cancer survivors return to work, very often they’re absent from work for several months, and as many as 53% of cancer survivors lose their job or quit working over a 6-year period following their diagnosis,” he reported.

A number of factors affect a person’s ability to return to work after a cancer diagnosis, including physical symptoms, poor sleep, daytime fatigue, and decreased productivity. But rehabilitation medicine can help improve an individual’s ability to work by minimizing physical impairments and improving endurance and strength.

Prehab versus Rehab

Prehabilitation is the time between a cancer diagnosis and the start of treatment, and it establishes the baseline level of functioning for an individual.

“We can use this time to identify and treat any preexisting impairments, and also to help reduce the incidence and severity of future impairments,” he said. “It’s also a very good time to promote physical and psychological health.”

There are various possible components of a prehab program, but some of the fundamentals include nutritional counseling, anxiety reduction and smoking cessation as needed, as well as general exercise and identifying and assessing impairments early, then intervening as necessary.

Rehabilitation, on the other hand, can occur before, during, and after cancer treatment, well into survivorship, and into the advanced stages of cancer. “Rehabilitation is a team activity that involves people in rehabilitation medicine, physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech and language pathologists, psychologists, social workers, vocational rehab, and obviously nursing,” he said.

Rehabilitation can be highly effective in reducing the impact of impairments and maximizing an individual’s level of functioning, but it can also serve as an opportunity for surveillance of cancer-related impairments (CRIs) and loss of function. “Early intervention is key to minimize the impact,” he added.

Barriers to Provision of Rehabilitative Services and Role of Navigators

“The barrier that I come across all the time is access to care,” said Dr Cristian. “There’s a lack of patient and caregiver education about cancer-specific impairments and rehabilitative interventions.”

Geographic and health insurance barriers add to the lack of access, as well as work-related restrictions, medical illness, responsibilities of child/parent care, and being “too busy” to attend medical appointments. However, navigators can help bridge these barriers through early identification of impairments, as well as by advocating for patients to receive rehabilitative interventions, he said.

Frailty in Cancer

According to Dr Cristian, several different factors can contribute to CRIs, but 4 fundamental components tend to lead to them.

“Besides the actual characteristics of the cancer, like location, extent, and severity, I think the 4 fundamental components that contribute to CRIs are (1) chemotherapy/immunotherapy/antihormonal therapy, (2) radiation therapy, (3) cancer surgery, and (4) age-related changes/preexisting conditions,” he said.

He also refers to the “layers of disability” that can lead to frailty in particular, including those age-related changes, comorbid conditions, preexisting conditions, cancer characteristics, and cancer treatment–related toxicity.

A high prevalence of frailty is present in patients with cancer. Approximately 42% of older cancer patients are frail or prefrail, and frailty is associated with increased all-cause mortality. Treatment complications are also more frequent in frail patients with cancer (ie, intolerance to cancer treatment/intensity and postoperative complications).

Frail older adults are also less likely to complete their treatments due to a variety of factors, including an amplified experience of side effects, a decline in clinical status, increased toxicity, and frequent hospitalizations.

“One interesting thing to note is that, in individuals with cancer over the age of 65, there’s a very high incidence of falling. If it’s advanced cancer, 50% fall, but 61% of the falls can result in injury,” he noted. “Rehabilitative medicine can help not only to identify those at risk and to intervene early, but if they should have sustained injuries after a fall, we can address those as well.”

The Impact of CRIs

Dr Cristian noted the commonality of a clustering of cancer/cancer treatment–related impairments. “It’s very common for patients to have multiple impairments coexisting at the same time,” he noted. “For example, patients with breast cancer might have shoulder dysfunction, lymphedema, and peripheral neuropathy.”

He also pointed out just how impactful these CRIs can be for some individuals, and how important it is to work toward mitigating them. For example, after treatment for head and neck cancer, a person might have gone through surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy and beaten their cancer. But after treatment, they are at a significantly increased risk of aspiration pneumonia due to those therapies, as well as up to a 60% rate of psychosocial distress with an “astonishing” rate of suicide that is 4 times that of the general population.

“That’s a tragedy to me, an almost 60% incidence of aspiration pneumonia with a 9% mortality,” he said. “So imagine that you beat cancer, but die of aspiration. That’s something we should work toward minimizing. And I do believe that rehabilitative medicine interventions that address swallowing dysfunction, neck lymphedema, and neuropathy [in patients with head and neck cancer] can help minimize this to a certain extent.”

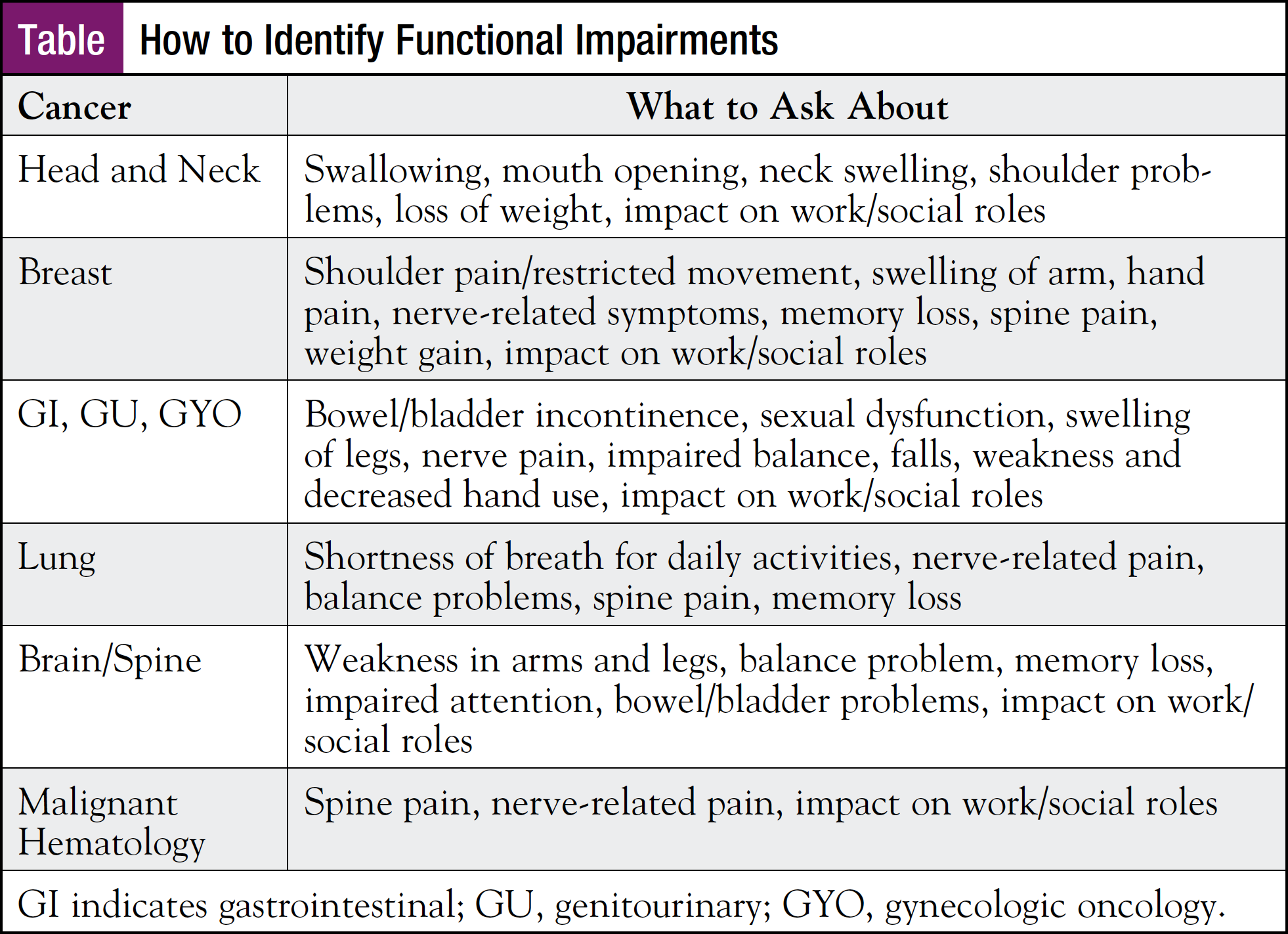

Dr Cristian shared a reference slide that nurse navigators can use to identify functional impairments in patients with different types of malignancies (Table). “These are typically the things that I ask our patients about to clue me in to their functional limitations by type of cancer,” he said. “I think if you have this as part of your toolkit, it could be very helpful in identifying functional and physical impairments.”

Additionally, as a simple screening method that can be implemented in any busy clinic, he recommends referring any patients with the following characteristics for cancer rehabilitation:

- Cannot raise their arm overhead to wave hello

- Cannot stand on 1 leg for 10 seconds

- Cannot get up out of a chair 10 times in 30 seconds

- Anyone who would benefit from a clinical trial but is considered too frail to participate

- All stage IV cancer patients