Background: A patient navigator is a health professional who partners with patients, serving as an advocate and guide, prioritizing a patient’s needs when working through the obstacles of the healthcare system to achieve optimal outcomes. Oncology patients undergoing treatment may have oncology nurse navigators as part of the care team. Navigators have the potential to improve outcomes in patients, and emergency department utilization may potentially be affected by nurse navigators.

Objective: The purpose of this study is to determine if oncology patients who were assigned nurse navigators utilized the emergency department differently than patients who did not have a nurse navigator.

Methods: We conducted a retrospective analysis of emergency visits from 2 acute care facilities in a Western state over 3 years, comparing frequency of emergency department visits and descriptive characteristics of navigated with non-navigated oncology patients.

Results: Statistical comparison controlling for differences indicated navigated patients utilized the emergency department more frequently. We identified characteristics of navigated patients as having advanced-stage cancers, higher number of comorbidities, being single, and having chemotherapy as part of the cancer treatment.

Conclusion: Navigated patients showed a higher frequency of emergency department utilization. Insights from measuring navigated patients’ emergency department use helped us define parameters to quantify the impact of oncology nurse navigator (ONN) programs. Consideration in deciding which clinical outcomes to measure should be based on the availability of accurate data provided by ONNs. Analyzing the data from emergency department visits among navigated and non-navigated oncology patients highlights opportunities for high(er)-risk and vulnerable cancer patients to be identified and supported earlier in their cancer process.

Nurse Navigators in Oncology

The role of the oncology nurse navigator (ONN) is to establish a collaborative relationship with the cancer patient at diagnosis, identify barriers or potential barriers to treatment, and then work with patients to overcome these barriers. In the course of receiving treatment for cancer, patients may face challenges related to financial/insurance issues, lack of understandable cancer information, limited social support, and unreliable transportation.1,2 Being diagnosed with cancer can be overwhelming, making these barriers even more difficult to cope with on a consistent basis. Patients and their families facing the diagnosis of cancer can feel lost, confused, and fearful of the healthcare system.3 The navigator works to connect patients to resources in their communities, provide education to help patients more fully understand their diagnosis and treatment options, and to ultimately empower the patients to advocate for themselves. Some of the most important barriers navigators have the potential to improve are coordination of care, decreasing wait times, and improving communication when complex patients may experience fragmented care among multiple providers, often within the same system.4 A navigator seeks to connect all the parts, pieces, and players; the ultimate goal is to facilitate the continuity of the prescribed treatment plan to provide for the best possible outcome.

Studies also show early navigation helps patients be more prepared and informed, enabling them to understand their proposed treatment plans at appointments.5,6 Actions such as community events for prevention and early detection of cancer and education to promote healthy lifestyle changes can support the growth of a navigation program and result in higher patient satisfaction scores and improvements in timeliness of care.7

Studies examining the use of navigators associated with emergency department utilization show patient navigation overall has an impact on lowering the frequency of emergency department usage.8-10 Noncancer patient data demonstrate that cost-savings from reduced primary care–related emergency department visits in navigated patients are greater than the cost of emergency department visits from non-navigated patients.10 Common themes of patients who use the emergency department over their primary care clinic include not having insurance, long wait times to see a primary care physician, belief that the emergency department doctor will provide higher-quality care, and lack of understanding about proper use of emergency services.11

To date, minimal data have been published looking specifically at oncology patient emergency department use and navigation. Among cancer patients, approximately 68% utilize the emergency department within 180 days of diagnosis.12 Preliminary case study evidence demonstrates the potential for navigation to reduce costs by decreasing unnecessary resource utilization, such as emergency department use.13 The expanded role of nurse navigation with care coordination has shown immediate cost-savings as a result of improvements in the utilization of emergency department visits, hospitalization, supportive care services, palliative care, and hospice care.14 As nurse navigation expands with care coordination, there is a need for innovative models that result in improvements in the utilization in these areas.15

The aim of this study is to determine whether oncology patients who are navigated utilize the emergency department less frequently than oncology patients who do not have a navigator. We gathered and analyzed data detailing emergency department visits among navigated and non-navigated oncology patients within 2 major hospitals in the northern California region to provide insight into the impact of a navigation program and to highlight vulnerable populations.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis of patients to determine if emergency department utilization is lower in oncology patients who received patient navigation compared with patients who did not receive patient navigation. We obtained institutional review board approval from the healthcare system. The study time frame was from January 1, 2015, to January 1, 2018. Any patient who received a cancer diagnosis between January 1, 2015, and January 1, 2018, had their emergency department visits tracked 365 days after the cancer diagnosis. During the time of this study, this health organization had a patient navigation program with 6 nurse navigators. Patients were routed to the nurse navigation program based on physician referral. Physicians may or may not offer navigation based on sociological, biological, and psychological factors that affect a patient’s ability to access quality healthcare. It is preferred that patients are referred to navigation at the time of cancer diagnosis so a proactive approach can be used to prevent barriers to care; however, referrals to navigation can be accepted at any time. To date, the institution has 10 nurse navigators and sees approximately 1800 cancer patients per year.

Sample and Setting

Data were utilized from 2 hospitals located in urban areas that primarily care for the underserved and lower socioeconomic communities. These hospitals act as safety net healthcare for the greater Sacramento area. Although the hospitals are part of a larger health system, the navigation program and electronic documentation only included the 2 participating hospitals.

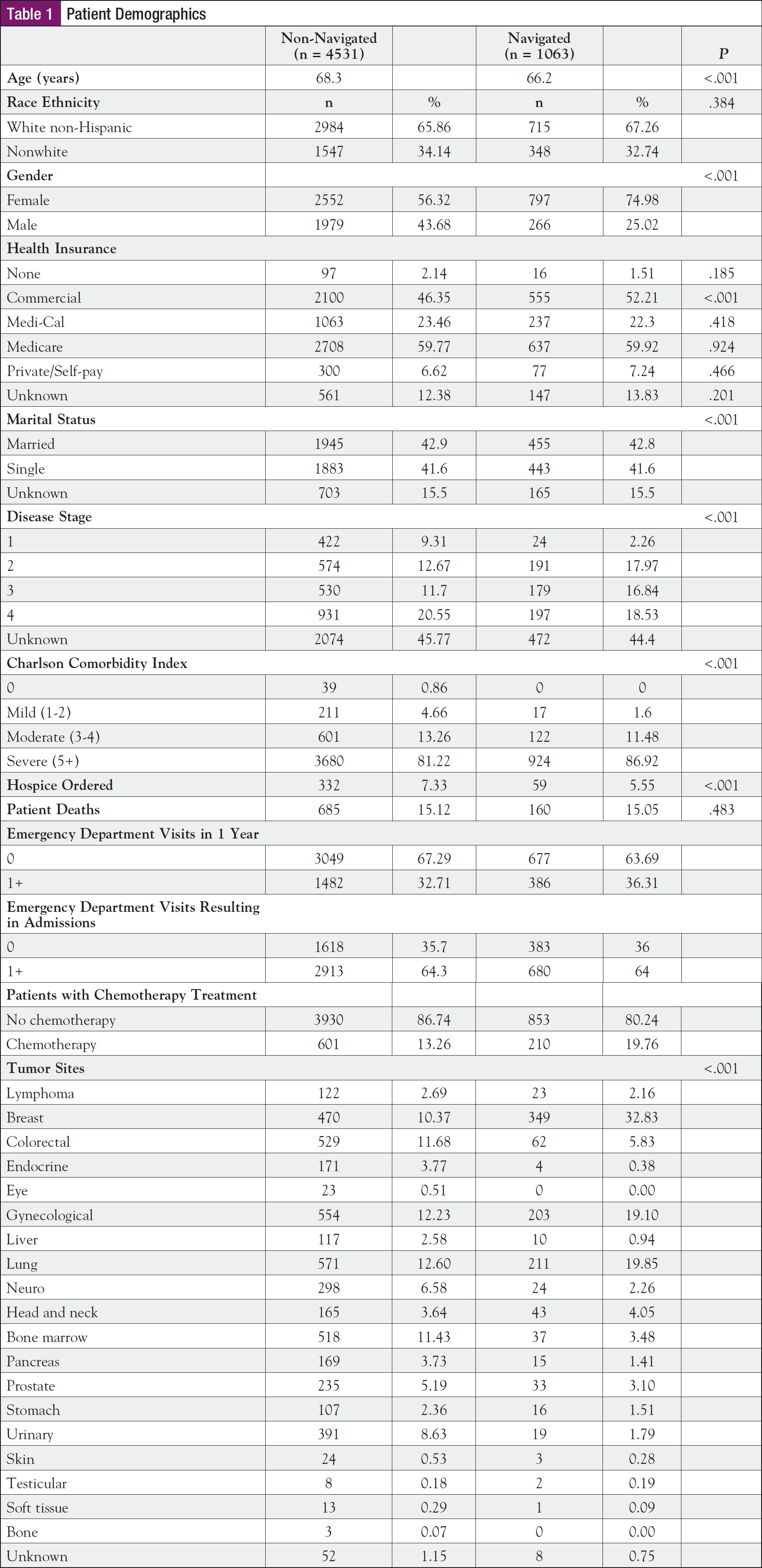

Electronic health record data were queried for all patients who received a cancer diagnosis between the study time frames. Twenty cancer diagnoses included breast, colorectal, gynecological, liver, and lung (Table 1). Patient records were excluded if they did not have a cancer diagnosis or if they were not treated at the 2 study facilities during the study time frame.

Data Collection and Analysis

Data were collected and combined from 3 sources: a cancer registry database that provides diagnosis data, medical health record information, and a software platform that collects nurse navigator documentation. Records were linked by patient medical record numbers and then deidentified for analysis. We queried the electronic health record using identified lists of patients by their cancer diagnosis date. Data were queried from 365 days after the diagnosis date, including whether they visited the emergency department at 1 of the 2 study facilities. Finally, we used the navigation documentation to indicate which patient records received navigation, and patients were coded as having or not having navigation services.

Patient characteristics queried for analysis included age, ethnicity, gender, marital status, and health insurance status. In addition to the patient’s cancer diagnosis, we also queried the patient’s disease progression stage, chemotherapy treatment, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, whether the patient had hospice ordered, and whether the patient expired. Finally, we collected and categorized the major complaints documented during emergency department visits. The primary tumor site was also documented.

Mean comparisons were performed using a t test to quantify differences between group characteristics and the main outcome, emergency department utilization. We used logistic stepwise regression analysis to control for differences in group characteristics on emergency department utilization.

Rates of use before and after navigation were compared. Finally, we conducted a post hoc exploratory analysis of group differences (cancer type and emergency department diagnosis) to further understand outcome differences between groups. We used the standard .05 alpha level of significance for all statistical calculations (P ≥.05).

Results

Table 1 describes the patient demographics for the sample. Cancer types varied significantly among both navigated and non-navigated groups (P <.001). There was a relatively high prevalence of breast, gynecological, and lung cancer among the navigated patients and considerable variability in cancer types among non-navigated patients. Differences were also noted in stage, hospice care, and comorbidities. Patients who were navigated had a higher percentage of stages 2, 3, and 4 (53.3%) compared with those who were in the non-navigated sample (44.9%). There were more non-navigated patients discharged to hospice (6.9%) compared with navigated patients (3.2%) (P <.001). Patients in the navigated group had higher percentages of severe comorbidity scores (86.9%) compared with the non-navigated group (81.2%) (P <.001).

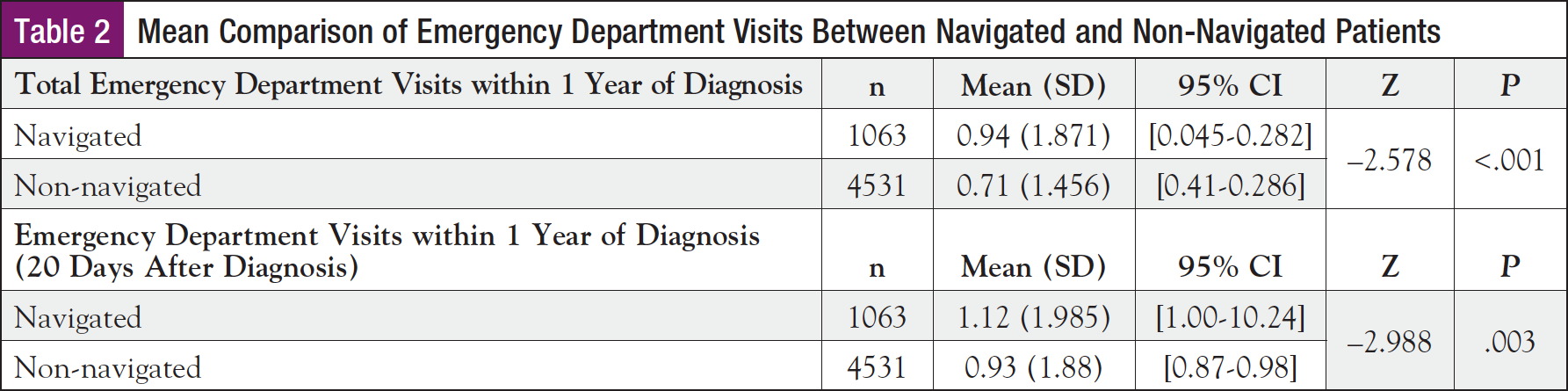

Further analysis revealed that non-navigated patients had fewer emergency department visits (M = 0.71, SD = 1.456) than patients who were navigated (M = 0.94, SD = 1.871; P <.001) over the course of 365 days after cancer diagnosis (Table 2). Analysis of the start date of navigation services indicated the median days between patient diagnosis and the start of navigation services was 20 days. Additional analysis to compare the number of visits of navigated and non-navigated patients 20 days after diagnosis also showed that non-navigated patients had fewer emergency department visits (M = 0.93, SD = 1.88) than patients who were navigated (M = 1.12, SD = 1.985; P = .003).

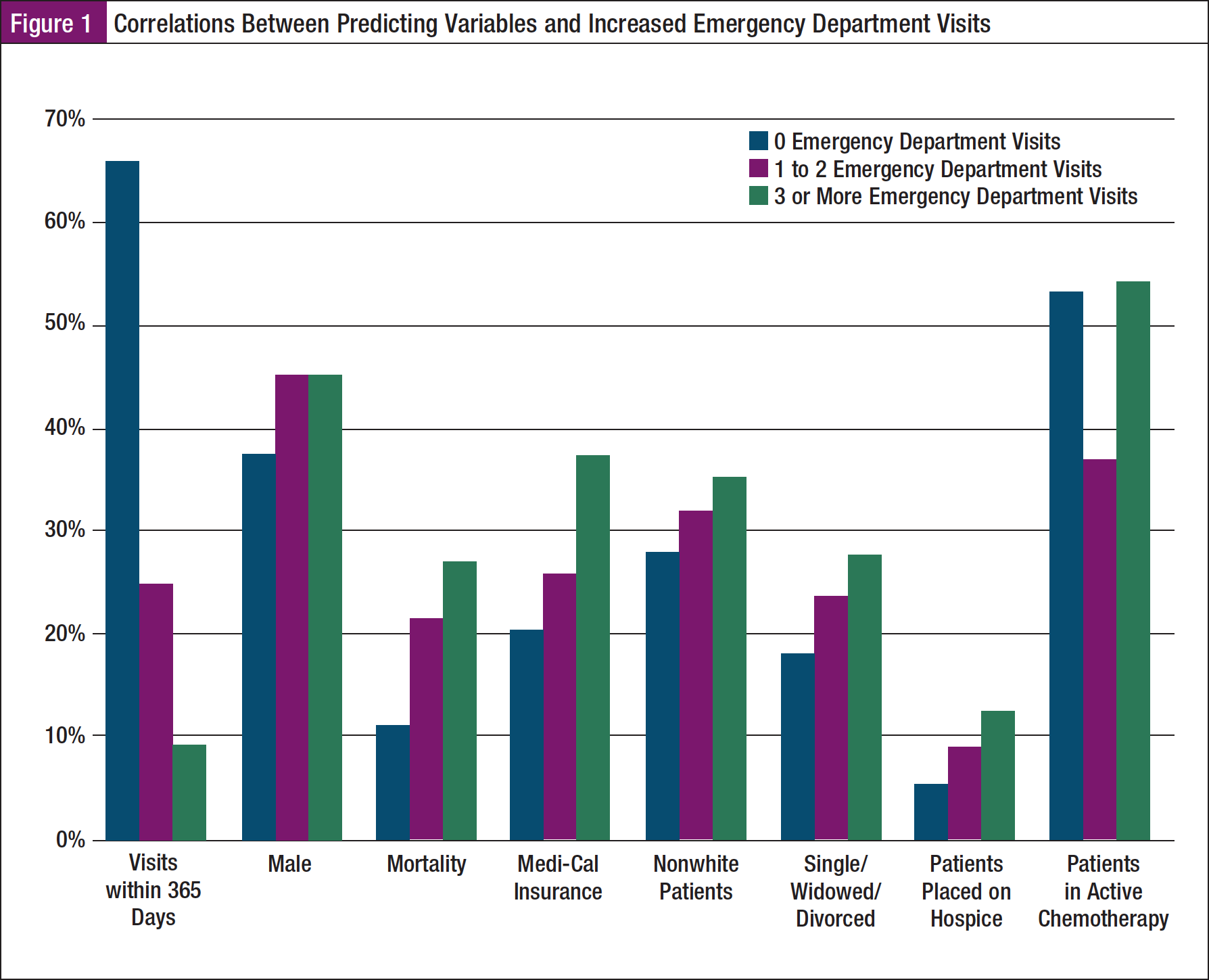

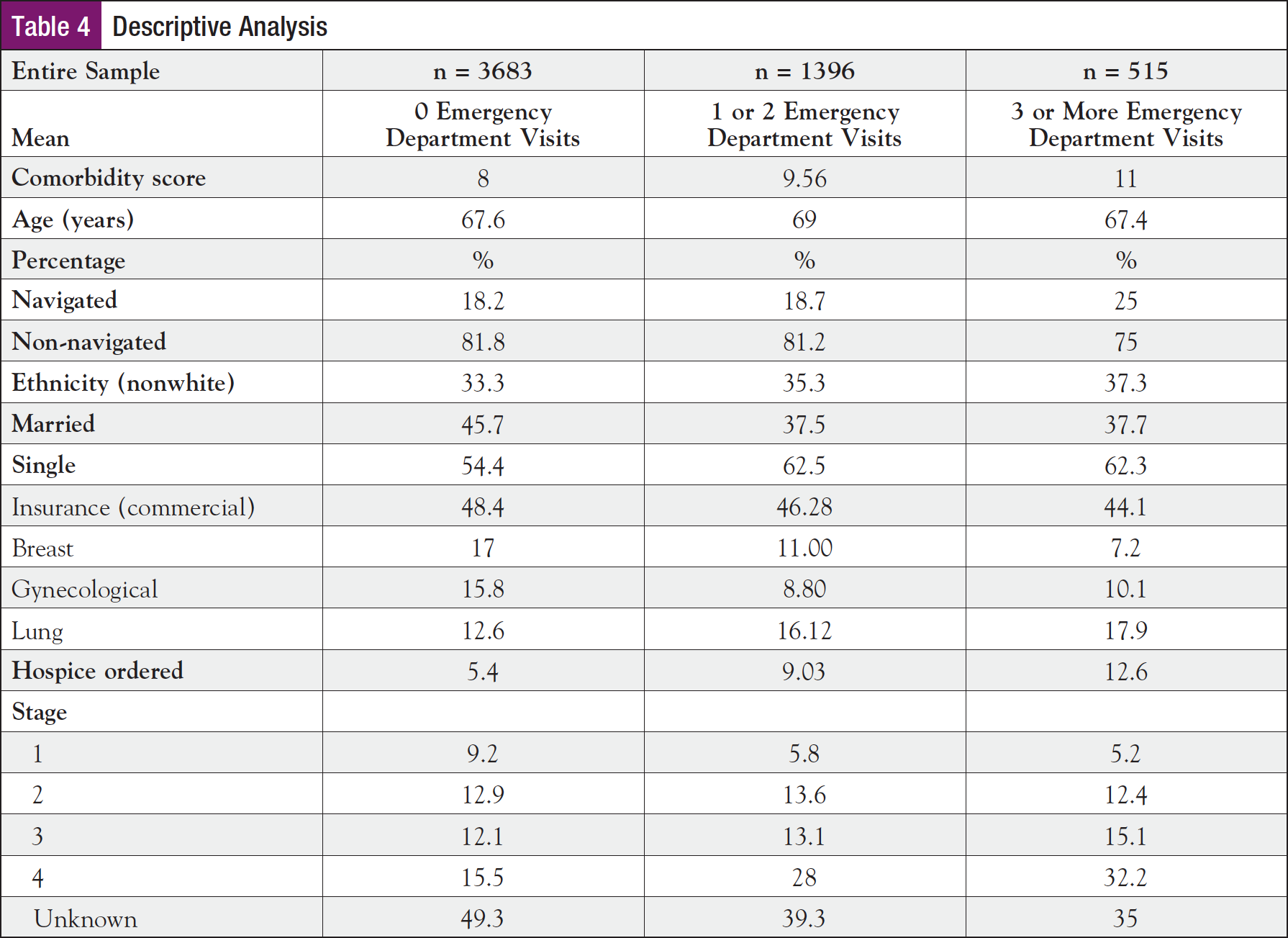

In a linear stepwise multiple regression analysis (Table 3), several variables in the model (comorbidity score, age, tumor site, navigation, hospice, stage, marital status, and insurance) were found to be significant predictors (P ≤.05) of emergency department use. Overall, these predictors account for 9.2% of the variability observed in the total number of emergency department visits within 365 days of a cancer diagnosis (Figure 1). These findings are supported by a descriptive analysis in Table 4, demonstrating positive correlations between the number of emergency department visits and the corresponding predictor variables. Controlling for significant differences between groups, results indicate non-navigated patients are less likely to visit the emergency department than navigated patients (b = –.309; 95% CI, –.455, –1.63; P <.001).

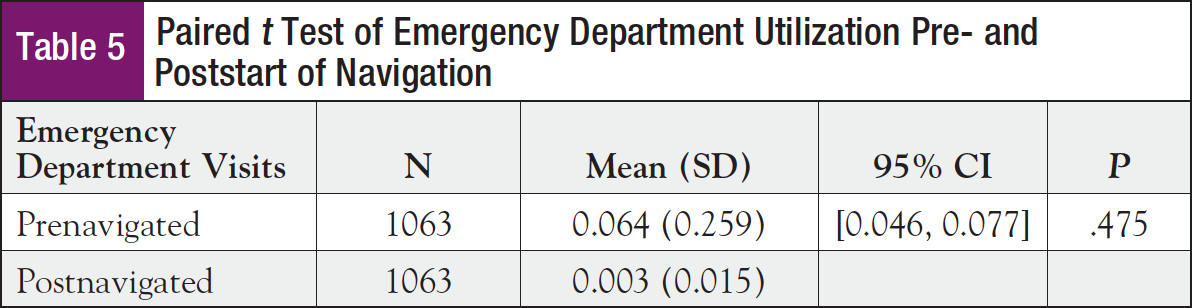

Results of the paired t test (Table 5) among the navigated patients indicated a difference of monthly emergency department use for those patients prior to the start of navigation (M = 0.064, SD = 0.259) compared with after being assigned a navigator (M = 0.003, SD = 0.015). Despite the statistical insignificance (P = .475), these findings may plausibly be considered to be practically significant in light of the substantial 95% reduction in emergency department utilization, suggesting that navigation had a notable effect. The mean number of prenavigated days for this sample is 58.3 days.

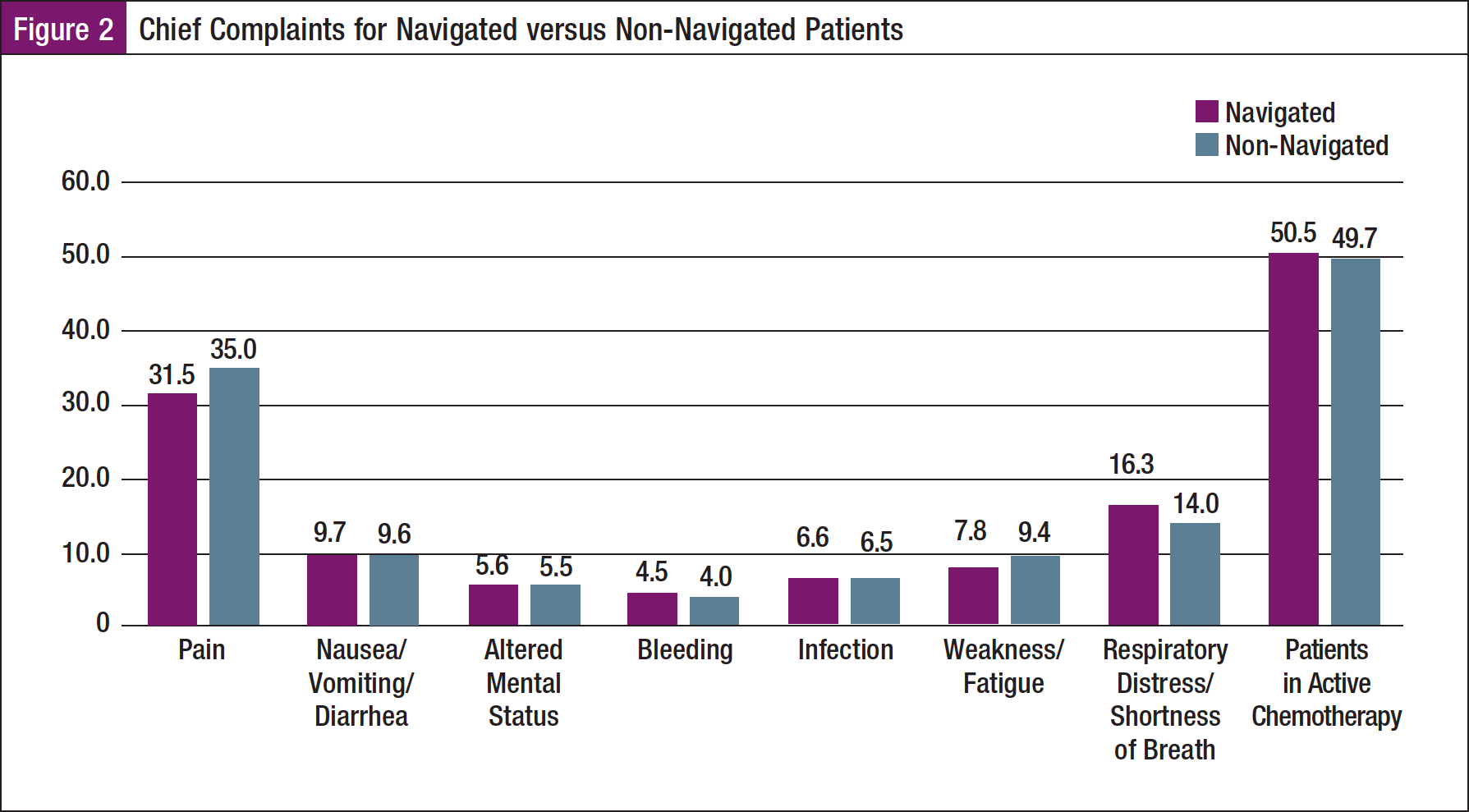

We conducted additional descriptive analysis to further explore the findings related to navigated patients having higher emergency department utilization, including frequency analysis of the patients’ chief complaints (Figure 2). The most frequent reasons for emergency department visits for all oncology patients (navigated and non-navigated), accounting for 84.0%, included pain (n = 35.0%), respiratory issues (n = 14.0%), nausea/vomiting/diarrhea (n = 9.6%), fatigue/weakness (n = 9.4%), infection (n = 6.5%), altered mental status (n = 5.5%), and bleeding issues (n = 4.0%). Among this group, 49.7% of the patients who visited an emergency department were experiencing active chemotherapy treatment or had chemotherapy within 365 days of their diagnosis. When comparing navigated patients with non-navigated patients who came to the emergency department, fewer navigated patients had complaints of pain, whereas more presented with respiratory issues (P <.001).

Discussion

In addition to improving care delivery and patient satisfaction, nurse navigation programs must consistently demonstrate their empirical value and influence on patient outcomes. There is an ongoing need for data collection of quality metrics within navigation programs to support the value of these programs, specifically as related to hospital readmissions, emergency utilizations, and costs.16,17 Moreover, consensus about the nurse navigator’s role makes quantifying the value of navigation more challenging.18 In 2017, the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators (AONN+) created a movement to standardizing metrics for navigation programs across the United States.19 The goal is to support the value of nurse navigation and promote the growth of navigation programs. Understanding the processes and outcomes associated with a nurse navigation program comes from exploring the associated data of patients, processes, and outcomes. In this study, we examined the number of times oncology patients visited the emergency department in a 1-year period from 2 facilities, and whether they had an ONN associated with their care.

Our findings indicate significant differences in patient characteristics between patients who did and did not have a nurse navigator, as well as higher emergency department utilization among navigated patients. Potential reasons navigated patients utilized the emergency department more frequently may be multifaceted and require further exploration. Of note, in this study, cancer patients with higher acuity were referred to navigation services. In addition to higher proportions of advanced cancer, the patients in the navigated group also had higher comorbidity scores; these factors may (partially) explain their higher emergency department utilization. Although this was accounted for in modeling, other noncancer studies have shown that low income and poor health are strong predictors of emergency department utilization even after adjusting for other variables.20

Emergency department use among the general population is associated with limited access to ambulatory care and primary care providers.20 As the hospitals in this sample were primarily safety net hospitals, the potential to access care may have been a concern for this patient population setting. In presenting our findings to the study hospital nurse navigators, discussion involved encouraging patients to go to the emergency department when they were unable to address concerns through ambulatory settings. Additionally, patients reported a preference for using the emergency department as it is perceived as being a higher quality of care that provides rapid confirmation and reassurance.11

A potential area for opportunity to improve navigation services is to start sooner. The navigation program in this study had a median of 22 days between their cancer diagnoses and the commencement of nurse navigation; many factors in the initial months of diagnosis can be supported by navigation. The first 3 weeks of a newly diagnosed cancer patient tend to be the busiest time as they are getting additional imaging, labs, tests, procedures, and consults with other specialists to expedite their cancer treatment and are likely to be experiencing emotional distress.21

There is also opportunity to support specific target populations, as we found patient characteristics related to emergency department utilization. The navigated sample had higher proportions of patients identified as separated, divorced, or single, which could imply lack of social support. Nurse navigation is most effective when it is introduced to the patient closer to their (date of) diagnosis since there is a greater opportunity to recognize and avoid a variety of obstacles.21 By standardizing the referral process, higher-acuity cancer patients could be referred to nurse navigation sooner, which could contribute to a more optimal outcome.22

Implications

Although patient navigation began in the early 1990s to improve cancer care, the specialization in patient navigation is still an evolving role for nursing. The Oncology Nursing Society (ONS) published the Oncology Nurse Navigator Core Competencies in 2013 and revised these competencies in 2017.23 They outline the fundamental knowledge and skills that novice ONNs should have or acquire during their first 1 to 2 years in the role.23 A survey in 2017 of ONNs showed 83% were registered nurses, 57% were self-taught on the roles and functions of a navigator, and 89% of respondents reported that the lack of staff/provider clarity on navigation roles was the most significant challenge to navigation programs.18

The unevenness of education, expertise, and standardized processes among nurse navigators can contribute to the over- or underestimation of their impact on the healthcare system. Variability in the implementation and processes associated with nurse navigation programs can influence outcomes, including type of staff, team size, training, organizational approach, and strategy.24,25 The clinical outcome of higher emergency department use among navigated cancer patients may be related to a lack of standardized processes, presenting an opportunity for navigation teams to implement a quality improvement. For example, after presenting study findings, the study site navigation program undertook quality improvement work to improve the referral process for patients, including implementing best practices such as identifying patients for navigation closer to the time of diagnosis. As most cancer patients are referred to nurse navigation by a member of their healthcare team, referrals can be limited if the physician and staff lack knowledge of the nurse navigator’s role, purpose, or existence. Physicians may believe that navigation services are reserved exclusively for complex cancer patients when in reality the role of the navigator is to support the patient from experiencing the setbacks in the first place. Increasing the number of navigation programs that adopt ONS Core Competencies as a requirement of training and knowledge for their navigators has the potential to support the growth and standardization of such professional practices in servicing these vulnerable patients.

Limitations

This study is limited to retrospective data queried from a 3-year period, analyzing patients for a 1-year period from 2 facilities. As with previous research,26 a randomized, controlled trial assessing the impact of nurse navigators earlier in cancer care may yield different results. Future research should include clinical outcomes in addition to emergency department utilization, specifically outcomes that are improved by early use of navigation services. This has the potential to identify effective entry points for nurse navigators and identify those patients who would benefit the most.

The logistic regression identified stage as a predicting variable in emergency department utilization. Our sample included the cancer stage of each patient; however, a high proportion of stages were classified as unknown (45%). This limits the true understanding of knowing if the navigated patients had a higher number of advanced cancers.

Another key limitation of this study is how patients were classified as navigated. The nurse navigation team at the time of the study used a separate electronic interface that only allowed for narrative notes when charting their intervention for patients. Unable to pull any data from narrative notes, patients were labeled as “navigated” without any substantiating data other than merely being associated with a nurse navigator. Navigation programs struggle to prove their effectiveness due to the lack of capturing evidence-based metrics through documentation.26 Future research on improving documentation for nurse navigation teams and how they collect metrics is vital to demonstrate value to their healthcare organizations and serve as a valuable tool in quality improvement.22 The collection of data for standardized metrics can produce essential knowledge required to develop effective processes. These processes can then be shared with other nurse navigation programs and ultimately improve clinical outcomes for cancer patients universally.

Conclusion

Nurse navigation programs have consistently demonstrated improvement in patient experience, satisfaction, care coordination, and reducing problems in caring for oncology patients. Understanding and eliminating healthcare disparities is a critical element of the ONN’s role. This is pivotal in identifying the appropriate interventions in overcoming barriers.27 To demonstrate value on complex outcomes, such as the frequency of patient emergency department visits, ONNs should evaluate their processes and data to ensure best practices. Nurse navigation should evaluate systemic barriers in the current healthcare system that may drive patients to use the emergency department rather than their primary care provider, working with stakeholders and leadership to implement quality improvement practices that support optimizing care and ongoing quality improvement.

References

- Ramsey S, Whitley E, Mears VW, et al. Evaluating the cost-effectiveness of cancer patient navigation programs: conceptual and practical issues. Cancer. 2009;115:5394-5403.

- Gonzalo MB, House L, Santiago K, et al. Access to care in cancer: barriers and challenges. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(suppl). Abstract 33.

- Linden W, Vodermaier A, Mackenzie R, Greig D. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J Affect Disord. 2012;141:343-351.

- Malone P, Bruno L. Patient satisfaction with oncology nurse navigation services. Journal of Oncology Navigation & Survivorship. 2016;7(11):20-26.

- Psooy BJ, Schreuer D, Borgaonkar J, Caines JS. Patient navigation: improving timeliness in the diagnosis of breast abnormalities. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2004;55:145-150.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Establishing Effective Patient Navigation Programs in Oncology: Proceedings of a Workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2018. https://doi.org/10.17226/25073.

- Wells KJ, Campbell K, Kumar A, et al. Effects of patient navigation on satisfaction with cancer care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26:1369-1382.

- Seaberg D, Elseroad S, Dumas M, et al. Patient navigation for patients frequently visiting the emergency department: a randomized, controlled trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24:1327-1333.

- Garbers S, Peretz P, Greca E, et al. Urban patient navigator program associated with decreased emergency department use, and increased primary care use, among vulnerable patients. Journal of Community Medicine & Health Education. 2016;6(3):440.

- Enard KR, Ganelin DM. Reducing preventable emergency department utilization and costs by using community health workers as patient navigators. J Healthc Manag. 2013;58:412-427.

- Coster JE, Turner JK, Bradbury D, Cantrell A. Why do people choose emergency and urgent care services? A rapid review utilizing a systematic literature search and narrative synthesis. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24:1137-1149.

- Lash RS, Bell JF, Bold RJ, et al. Emergency department use by recently diagnosed cancer patients in California. J Community Support Oncol. 2017;15:95-102.

- Kline RM, Rocque GB, Rohan EA, et al. Patient navigation in cancer: the business case to support clinical needs. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15:585-590.

- Costich TD, Lee FC. Improving cancer care in a Kentucky managed care plan: a case study of cancer disease management. Dis Manag. 2003;6:9-20.

- Colligan EM, Ewald E, Ruiz S, et al. Innovative oncology care models improve end-of-life quality, reduce utilization and spending. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36:433-440.

- Guadagnolo BA, Dohan D, Raich P. Metrics for evaluating patient navigation during cancer diagnosis and treatment: crafting a policy-relevant research agenda for patient navigation in cancer care. Cancer. 2011;117(15 Suppl):3565-3574.

- Strusowski T, Johnston D. National evidence-based oncology navigation metrics: multisite exploratory study to demonstrate value and sustainability of navigation programs. J Clin Oncol. 2018;38(suppl). Abstract e14040.

- Rasulnia M, Sih-Meynier R. The roles and challenges of oncology navigators: a national survey. Journal of Oncology Navigation & Survivorship. 2017;8(1):14-22.

- Strusowski T, Stapp J. Patient navigation metrics. Oncology Issues. 2016;31(1):62-69.

- Goodell S, DeLia D, Cantor JC. Emergency department utilization and capacity. The Synthesis Project. Policy Brief No. 17. July 2009. http://cshp.rutgers.edu/Downloads/8120.pdf. Accessed November 22, 2021.

- Ludman EJ, McCorkle R, Bowles EA, et al. Do depressed newly diagnosed cancer patients differentially benefit from nurse navigation? Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;37:236-239.

- Wagner EH, Ludman EJ, Aiello Bowles EJ, et al. Nurse navigators in early cancer care: a randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:12-18.

- Oncology Nursing Society. 2017 Oncology Nurse Navigator Core Competencies. www.ons.org/sites/default/files/2017-05/2017_Oncology_Nurse_Navigator

_Competencies.pdf. Accessed November 11, 2021. - Baileys K, McMullen L, Lubejko B, et al. Nurse navigator core competencies: an update to reflect the evolution of the role. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2018;22:272-281.

- Swanson JR, Strusowski P, Mack N, DeGroot J. Growing a navigation program. Using the NCCCP navigation assessment tool. Oncology Issues. 2012;27(4):36-45.

- Strusowski T. Navigation metrics and value-based care: measuring up. Association of Community Cancer Centers. www.accc-cancer.org/acccbuzz/blog-post-template/accc-buzz/2017/03/09/navigation-metrics-value-based-care-measuring-up. 2017. Accessed November 11, 2021.

- Shockney L. Team-Based Oncology Care: The Pivotal Role of Oncology Navigation. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2018.