Catherine E. Bailey, RN, BSN

Oncology Nurse Navigator

OSF HealthCare Saint Francis Medical Center, Peoria, IL

Megan L. Rappleyea, RN, MSN, OCN, CNE

Instructional Assistant Professor

Mennonite College of Nursing at Illinois State University, Normal, IL

Tenille Oderwald, MSN, RN, CN-BN

Manager, Outpatient Oncology Services

OSF HealthCare Saint Francis Medical Center, Peoria, IL

Christina L. Garcia, PhD, RN, NE-BC

Professor, Graduate Program, Lead Faculty – Nursing Management and Leadership, DNP Leadership, Saint Francis Medical Center

College of Nursing, Peoria, IL

Background: Patients with lung cancer often face significant rates of morbidity and mortality. The lung cancer nurse navigators at OSF HealthCare Saint Francis Medical Center noted substantial barriers to end-of-life discussion and planning among lung cancer patients. This patient population frequently approaches the end of their lives without having discussed their wishes with their families, resulting in increased distress for both patients and their loved ones. The oncology nurse navigator (ONN) has a well-developed relationship with the patient and is well-positioned to assist with advance care planning (ACP).

Objectives: This qualitative descriptive study explored the benefits of ACP as an expanded role for the ONN by describing the perspectives of appointed healthcare power of attorney (HCPOA) agents for lung cancer patients who had their ACP discussion led by an ONN.

Methods: The study employed a qualitative descriptive approach with qualitative content analysis of a semistructured interview with HCPOA agents. Analysis focused on describing the agents’ perspectives on ACP and their experiences with ONN facilitation of ACP.

Results: Nine HCPOA agents agreed to be interviewed for the study. One interviewee was noncontributory because they were unable to remember the details of the ACP session, and another was excluded due to technology failure; therefore, 7 total interviews were reviewed for themes. The themes describing HCPOA agents’ perspectives on ACP and experiences with ONN facilitation are helpfulness of the navigator, increased confidence in decision-making, emotional support throughout the ACP process, the thoroughness of the ACP session, and the emotional challenges of the ACP session.

Conclusions: HCPOA agents found ONN’s facilitation of ACP helpful and productive, suggesting that training ONNs to do this facilitation is valuable. Agents found it difficult to separate ACP facilitation from the broader experience of navigation. Given our experience, we conclude that ONN facilitation of ACP is feasible and acceptable to HCPOA agents supporting people living with lung cancer. Further exploration of ONNs leading ACP is warranted.

The role of the oncology nurse navigator (ONN) has and will continue to evolve to meet the ever-changing needs of cancer patients. As defined by the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators, the nurse navigator is a trained professional responsible for identifying barriers to timely access to care, and more specifically, acts as the central contact while coordinating all components in cancer care, including treatment, survivorship, and support.1 Cancer care can be extraordinarily complex with a sense of urgency, and often advance care planning (ACP) discussions are neglected at the time of diagnosis. Frequently end-of-life decisions are made when the patient begins to decline, not allowing these essential conversations to take place in an emotionally supportive atmosphere with sufficient time to objectively consider all the options. This situation can be frequently found in the lung cancer population, as their health can deteriorate quickly.

In 2021, lung cancer was estimated to be the second leading site of new cancer cases (235,760) and the leading cause of cancer-related mortality (131,880) in the United States.2 A diagnosis of lung cancer has major ramifications for patients and their families in discussing and planning for end of life. ACP is a process in which patients communicate their preferences for future end-of-life care that align with their values and beliefs and appoint a substitute healthcare decision maker while communicating these wishes with their loved ones and healthcare team.3

Several authors report investigations into the experience of the appointed surrogate decision makers or healthcare power of attorney (HCPOA) agents who are tasked with making decisions on behalf of the patient. A systematic review of 24 studies on the experiences and perceptions of surrogate decision makers conducted by Su and colleagues4 showed that surrogate decision-making at the end of life is not easy. A lack of information and knowledge inhibits the surrogate’s ability to comprehend treatment, outcomes, and prognosis, and they can experience emotional burden, particularly in surrogates from lower socioeconomic statuses. Knowing patient wishes relieved the surrogate’s burden. Su and colleagues established that most surrogate decision makers perceived nurses to offer more compassionate and clearer communication regarding end-of-life care decisions and often turned to them when there were perceived challenges related to communication with physicians.4 A study conducted by Ólafsdóttir and colleagues investigating nurse-facilitated ACP discussions between surrogate health decision makers and patients with lung cancer demonstrated that these discussions offered early in treatment or around the time of diagnosis were helpful and well received.5 Members of the healthcare team who have established long-term relationships with the patient and are involved in the complex coordination of their care, such as clinical nurse specialists and ONNs, are well-positioned to lead ACP discussions with patients and family members.6-10 In summary, ONNs hold a distinct position within the cancer care team, enabling them to lead ACP discussions between patients and family members.

Disease burden, disparities, and the need for early and expert communication surrounding end-of-life care for lung cancer patients and their appointed healthcare surrogates is clear. Nurses with established ongoing relationships who serve as coordinators and advocates are well positioned and needed in facilitating ACP. ONNs have frequent interaction with patients and family, often starting at the time of diagnosis and lasting across the continuum of their care. They are present during changes in status and care and are an integral part of the multidisciplinary team. In addition, the ONNs play key roles in empowering patients and family members with access to healthcare resources.4 Although the purpose of ACP and the role of the ONN are well aligned, ACP facilitation is not a recognized standard role of the nurse navigator. This study aims to support the idea that leading ACP discussions can be an appropriate expanded role for the ONN by analyzing experiences of the appointed HCPOA agents of cancer patients who had their ACP session led by a trained navigator.

Oncology Nurse Navigator ACP Training

Two ONNs who specialize in lung cancer underwent an 8-hour standardized in-person multidisciplinary ACP training course offered by OSF HealthCare Saint Francis Medical Center (SFMC). The course included sessions covering the OSF Healthcare Care Decisions ACP model, legal considerations of ACP, how to complete the Illinois Power of Attorney for Health Care form and Discussion Record, and high-fidelity ACP session simulations with debriefing. At the end of the course, the navigators were certified to lead ACP discussions and complete all associated paperwork with patients.

Methods

Study Approach and Design

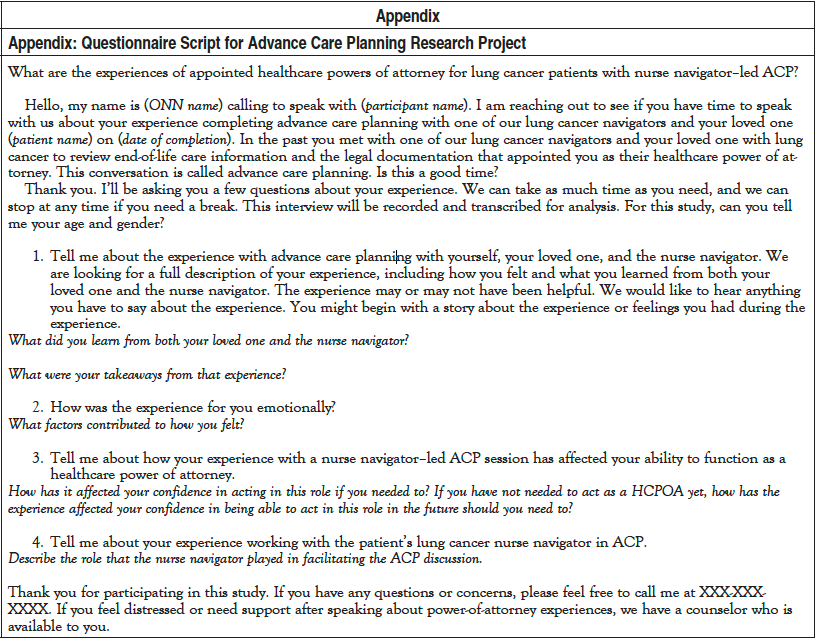

This study used qualitative content analysis, collecting data from HCPOA agents in semistructured interviews to learn about the experiences of appointed HCPOA agents who underwent an ACP session that was facilitated by the patient’s trained lung cancer navigator.

Setting and Intervention

The study was conducted at an outpatient cancer services department through OSF HealthCare SFMC. Approximately 400 new lung cancer patients are cared for by the ONNs each year at SFMC. The lung cancer ONNs offered an ACP session that included lung cancer patients and their intended HCPOA agents. This session was conducted within the first month following a cancer diagnosis. Information regarding ACP, appointing an HCPOA agent, and the discussion process was reviewed with patients, and an appointment with the navigators was offered. If the patient and caregivers were interested in completing ACP, an appointment was set up in a private room with the patient, intended HCPOA agent, and lung cancer navigator. ACP discussion facilitation was completed with patients and their appointed HCPOA agent utilizing the OSF Healthcare Care Decisions Advanced Care Planning Patient and Family Discussion Record and the Illinois Statutory Short Form Power of Attorney for Health Care. Immediately following the session, patients were provided with copies of their completed ACP and HCPOA form. The original copy was sent to the patient’s electronic medical records to be scanned into their EPIC account under the ACP tab. The data from the session, including patient identifiers, date of completion, and discussion facilitator, were entered into the Instant Data Entry Application (IDEA) database that is used by OSF HealthCare to track ACP completion.

Recruitment and Participants

This study used purposive sampling, seeking out potential participants who could speak to their own experiences of the navigator-led ACP session in alignment with the aim of the research. Potential participants were identified by reviewing entries in the IDEA database for lung cancer patients whose ACP session was facilitated by a trained lung cancer navigator with the appointed HCPOA agent present. The identified HCPOA agents were contacted and asked to participate in the study. HCPOA agents for patients both currently living and for those who were deceased were invited to take part. Exclusions included those in the database who did not have a nurse navigator–led ACP discussion, those patients who did not have cancer in the lung, and those HCPOA agents who were not present for the nurse navigator–led discussion. Potential participants who could not speak over the phone or whose interview did not capture clearly enough to transcribe the interview verbatim were also excluded.

A total of 29 potential participants were sent a letter using delivery confirmation provided by the United States Postal Service. The letter included an introductory page, a detailed description of the study and interview process, as well as counseling and support services information. This letter also confirmed that the interview was voluntary, and that all personal information was confidential and anonymous. Nine HCPOA agents agreed to be interviewed.

For consistency, only 1 investigator conducted the interviews. The manager of OSF Cancer Support Services at the time of the study conducted the interviews. She had no prior experience with descriptive qualitative research interviews. She reached out to each potential participant over the phone from a private office at her workplace. No one else was present during the interviews. To eliminate bias, interviews were conducted by an investigator who did not participate in the ACP session, and she had no prior relationship with any of the participants. The participants were made aware of the goals of the interviewer in the introductory letter that had been sent out. No further characteristics of the interviewer were revealed to the participants. In addition, for sensitivity to the participants, the investigator conducting the interview was aware if the patient who completed the ACP was alive or deceased. If the participant did not fully answer the questions, follow-up questions probed their perspective. No repeat interviews were conducted. The interviewer noted to each participant that if the nature of the topic caused any distress, the interview could be stopped at any point. In addition, each participant was offered counseling services at the end of the interview, although none of the participants felt it was necessary to pursue.

Data Collection and Management

Interviews used a semistructured guide (Appendix) to guide the conversation. The investigator conducting the interview recorded each conversation with an encrypted voice recorder to be transcribed and reviewed for data analysis. The interviewer took notes during each interview to assist with transcription. Interviews ranged from 10 to 60 minutes in length. The interviewing investigator transcribed each interview verbatim, assigning a participant number for identification. Demographic data were collected over the phone by the interviewer. Additional data were collected via chart review, including the patient’s stage at the time of the HCPOA completion, date ACP session and execution were completed, and the mortality status of the lung cancer patient at the time of study.

Data Analysis

One investigator coded all the data. The transcribed interviews were then reviewed for theme analysis by 2 other investigators to improve confirmability and trustworthiness. Data from the interviews and field notes were coded for content. Initial analysis inductively identified codes, which were then organized into themes using processes described by Doyle and colleagues11 and Hsieh and Shannon.12 First, data were analyzed using serial paraphrasing, which included paraphrasing data into summary sentences. These sentences were broken down into keywords and phrases to describe the experiences of the HCPOA agent during the ACP process. These themes were compiled into a codebook used to analyze the remaining data and further refine the themes as reported here. The data were recorded and organized using Microsoft Excel and were stored on a locked, encrypted flash drive. Participants did not have the opportunity to provide feedback on the findings.

Ethics

This study was reviewed and approved by the Peoria Institutional Review Board to determine any risks to the participants. Participants indicated their consent to participate by completing a telephone interview; no signed consent forms were collected. To protect confidentiality, participants were interviewed by telephone in a private office. The recordings and transcripts were coded with a number corresponding to an HCPOA agent’s (participant) name. All words and identifiable information were erased and marked with a blank space in the transcriptions. The interviewer coded participant information to keep identifiers blind to investigators analyzing data.

In recognition of the potential emotional stress that the interview may have caused the participants, information for counseling and supportive services was offered to participants in the research study consent letter and at the end of the interview. In addition, a debriefing time was provided after the interview for participants to ask questions and voice concerns. Finally, participants were reminded that they could choose to end the interview at any point.

Neither the participants nor researchers received incentives or financial support for the research.

Trustworthiness and Rigor

To eliminate bias, the investigator who conducted the interviews was not involved in the data analysis. Two separate investigators independently analyzed the data for themes. The analysis continued until repetition of patterns occurred in all themes and no new patterns were identified. Adherence to the COREQ checklist was used for reporting this qualitative analysis.

Results

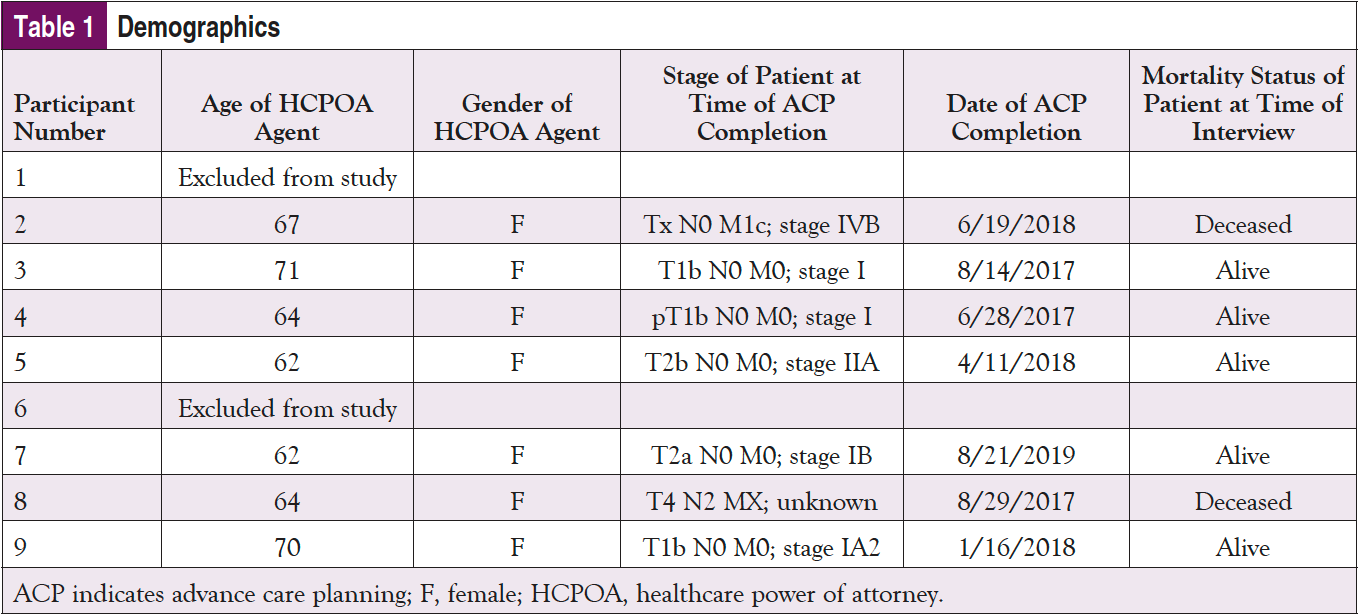

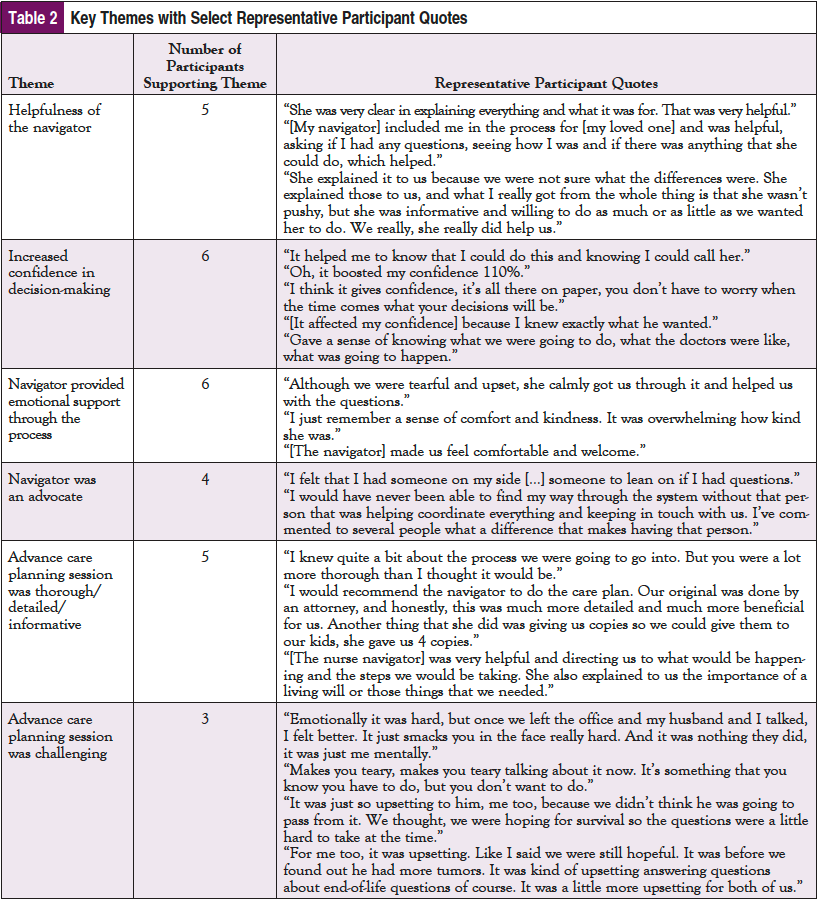

Nine HCPOA agents participated in the study. Their demographic characteristics are reported in Table 1. Five themes describe the agents’ perspective and experience on ACP facilitated by a trained ONN. These themes included the helpfulness of the navigator; increased confidence in decision-making; emotional support; ACP session was thorough, detailed, and informative; and the ACP session was emotionally challenging. The thematic analysis strongly indicated that most of the participants reported a positive experience with the ONN-led ACP session. Select quotes from the interviews that support these themes can be found in Table 2.

Helpfulness of the Navigator

The word “helpful” or “helped” in reference to the navigator and the information provided was used a total of 36 times across the interviews. A variety of comments were made indicating that the navigator was helpful in guiding discussion, answering questions, and clarifying the information. “She explained it to us because we were not sure what the differences were. She was informative and willing to do as much or as little as we wanted her to do.” Another participant stated, “She was very clear in explaining everything and what it was for. That was very helpful.” Helpfulness is imperative for patients to understand what is being discussed, and to feel supported during the ACP session.

Increased Confidence in Decision-Making

Four of the interviews indicated that the ACP session helped build confidence in their ability to make end-of-life decisions for their loved one. One person reported it “boosted my confidence 110%.” Another said, “I think it gives confidence, it’s all there on paper, you don’t have to worry when the time comes what your decisions will be.” A third participant stated, “It helped me to know that I could do this.” Confidence coincides with effective decision-making as it pertains to end-of-life decisions.

Navigator Provided Emotional Support

Five of the 7 participants specified that the ACP session was emotional due to the nature of the topic but reported that the navigator was a source of support and comfort throughout the process. One respondent said, “Although we were tearful and upset, she calmly got us through it and helped us with the questions.” Another participant indicated “I just remember a sense of comfort and kindness. It was overwhelming how kind she was.” Emotional support provided by the navigator is essential in end-of-life discussions as the nature of the topic can be very distressing.

ACP Session Was Thorough/Detailed/Informative

Four of the 7 participants spoke about the thoroughness and detail of the ACP session. One person compared it to their experience with completing a Living Will: “Our original was done by an attorney, and honestly, this was much more detailed and much more beneficial for us.” Another participant described the session as “a lot more thorough than I thought it would be.”

ACP Session Was Emotionally Challenging

One participant reported a negative experience due to the emotional nature of the discussion and personal lack of preparedness for facing the mortality of their loved one. The word “upset” or a form of it was used a total of 9 times within this interview alone. Regarding the navigator’s facilitation of the ACP session, the HCPOA agent said, “She was very careful and informative.” Four other participants also alluded to the emotional and mental challenges associated with the process of discussing end-of-life matters.

Discussion

The themes extracted from the data were mostly favorable upon review. The participants found the navigator to provide a safe, comfortable environment for complex, emotional conversations. They indicated that the in-depth discussion allowed for more confidence in end-of-life decision-making. One HCPOA agent indicated feeling unprepared to consider their loved one’s mortality. However, the agent did indicate that the unpleasant memory of the session was not reflective of the navigator, and the navigator was “careful and informative” during the session.

Although discussing end-of-life concepts remains emotionally challenging for cancer patients and their families, the interviews demonstrated that ONNs leading ACP sessions provide a therapeutic and supportive environment for patients and families to explore end-of-life decision- making. The overall themes of the interviews support the idea that ACP is a good fit as an expanded role for the ONN. One core participant even stated outright “I would recommend the nurse navigator do the care plan.”

The number of people available to be recruited to participate and the ultimate sample size are both limitations of this study. Further research on the benefits and effects of nurse navigator–led ACP is warranted, potentially across cancer centers and health systems. Future studies comparing the experiences of those who had their ACP session led by their ONN with those whose session was led by a different healthcare worker will enrich understanding to extend this role in ONN practice and are also needed.

The repeated topic of the ONN as an advocate emerged in this analysis. However, advocacy generally appeared in reference to the entire navigation experience and not specifically in relation to the ACP session. Therefore, it was not included as a theme representing the benefits of navigator-led ACP. Advocacy in the ONN role offers an opportunity for further research. Moreover, many participants appeared to have difficulty separating the event of the ACP session from the broad experience of navigation. The interviewer often had to redirect the conversations to the specific incidence of the ACP session, as the HCPOA agent would blend the navigation experience into their answers. For example, some of the participants discussed the lung cancer education provided by the ONN or how the nurse navigator provided care coordination, yet neither of these topics had to do with the ACP session. This blending of memories may have been reflective of the time that had passed between the ACP session and the interview. However, it may also warrant further exploration on whether this could indicate that having navigator-led ACP sessions results in ACP being a more natural, seamless part of the cancer journey instead of an isolated event in the person’s memory.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Sarah H. Kagan, PhD, RN, for her work as a mentor on this project.

There were no funding sources for this research study.

References

- Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators. Helpful Definitions. www.aonnonline.org/31-aonn/18-helpful-definitions. Accessed November 3, 2021.

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2021. www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer- facts-and-figures/2021/cancer-facts-and-figures-2021.pdf. 2021. Accessed June 16, 2021.

- Wasylynuk BA, Davison SN. An overview of advance care planning for patients with advanced chronic kidney disease: the basics. CANNT J. 2016; 26:24-29.

- Su Y, Yuki M, Hirayama K. The experiences and perspectives of family surrogate decision-makers: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103:1070-1081.

- Ólafsdóttir KL, Jónsdóttir H, Fridriksdóttir N, et al. Integrating nurse-facilitated advance care planning for patients newly diagnosed with advanced lung cancer. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2018;24:170-177.

- Boot M, Wilson C. Clinical nurse specialists’ perspectives on advance care planning conversations: a qualitative study. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2014;20:9-14.

- Clark MA, Ott M, Rogers ML, et al. Advance care planning as a shared endeavor: completion of ACP documents in a multidisciplinary cancer program. Psychooncology. 2017;26:67-73.

- Holland D, Vanderbroom CE, Dose AM. Nurse-led patient-centered advance care planning in primary care. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing. 2017;19(4):368-375.

- Rocque GB, Dionne-Odom JN, Huang CHS, et al. Implementation and impact of patient lay navigator-led advance care planning conversations. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53:682-692.

- O’Donnell A, Buffo A, Campbell TC, Ehlenbach WJ. The critical care nurse communicator program: an integrated primary palliative care intervention. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2020;32:265-279.

- Doyle L, McCabe C, Keogh B, et al. An overview of the qualitative descriptive design within nursing research. J Res Nurs. 2020;25:443-455.

- Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277-1288.