Background: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common leukemia in adults, and it has been shown to cause considerable symptom burden in both patients and their caregivers. Recently, studies have focused on quality-of-life (QOL) measures and the relationship with health outcomes. However, to date, the breadth of QOL domains and measures is not well represented in the literature, diminishing the ability to form specific questions and to develop a systematic review.

Objective: The objective of this scoping review was to investigate and analyze articles related to CLL patient and caregiver physical, psychological, social, and spiritual well-being published between January 1, 2015, and June 15, 2020. These articles will be used to provide an evidence base for the development of an integrative education tool to empower patients and their caregivers following a CLL diagnosis and throughout the continuum of care.

Methods: This scoping review considered all studies that addressed physical, psychological, social, and spiritual well-being of patients diagnosed with CLL or their caregivers. A 3-step search strategy was undertaken: (1) an initial limited search of PubMed; (2) an extensive search using all identified keywords and index terms; and (3) a hand search of the reference lists of included articles. This review was limited to studies published in English between January 1, 2015, and June 15, 2020. Reviewers extracted data independently; disagreements that arose between the reviewers were resolved via discussion or with a third reviewer.

Results: A total of 5629 articles were screened, 937 full-text publications were reviewed, and 75 relevant articles were identified. Most studies focused on physical well-being. Several review articles discussed treatment algorithms and consideration for treatment of patients with CLL. No articles evaluating the patient/caregiver relationship were identified, and only a single study was designed to assess caregiver health status.

Conclusion: The most commonly evaluated QOL component was physical well-being, whereas only a single article discussed spiritual well-being. Social well-being was discussed in 4 articles. Overall, 8 articles spanned the psychological and physical domains. Inclusion of all 4 QOL components will be beneficial for developing a patient education platform for patients and their caregivers following a diagnosis of CLL and throughout the care continuum.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common leukemia among adults, with an estimated 21,250 new cases and 4320 attributed deaths in 2021.1 Quality of life (QOL) is an important consideration for patients with cancer, and more studies have been designed to investigate its importance related to clinical decision-making among patients with leukemia in recent years.2 Depression, anxiety, fatigue, and medical comorbidities have been associated with future anxiety or depression symptoms among patients with CLL.3 However, the emotional and psychological impact of CLL on patients throughout the care continuum is not well understood.

The natural history of CLL is variable, with patient survival ranging from approximately 2 to 20 years.4 Therefore, investigation of the emotional and psychological impacts of CLL may need to be assessed over decades. Most patients with CLL follow a “watch and wait” approach whereby disease progression rate is determined and the patient is periodically assessed for symptom development.5

Caregivers, including friends or family members, have been demonstrated to be crucial for providing care for patients with advanced cancer.6,7 Considerable stamina is required to provide care for these patients, and it often leads to a negative impact on QOL and mood of the caregivers.8-10 At times, caregivers report psychological distress that exceeds the burden faced by patients with cancer, which highlights the importance of evaluating psychological well-being of caregivers of patients with cancer.11,12 As a patient’s disease progresses, the caregiver’s physical well-being has been reported to decrease.7 Furthermore, caregivers experience social demands in terms of social support, relationships, and financial burden.13 Together, these findings support the need for improved understanding of caregiver QOL and burden.

Following a diagnosis, healthcare providers and patients determine a course of care that is aligned with the patients’ values using shared decision-making. Following patient participation in shared decision-making, increased trust, more realistic perceptions of treatment expectations and risk, improved clinical and patient-reported outcomes, and increased patient satisfaction and treatment adherence have been reported.14,15 The initial step for shared decision-making is to gain the knowledge to support both preference- and value-based decisions, which can be achieved with the use of evidence-based educational tools.

Patient education has been demonstrated to contribute to improved knowledge; increased understanding of disease, including risk factors, prognosis, and the risk/benefit of various treatments; improved cognitive skills such as self-efficacy; and enhanced communication.16 Friends, family, and caregivers have been shown to influence health decisions as well. Health education should be designed with the consideration of patient benefits and barriers and external influences from family members and healthcare providers to enhance beneficial behaviors, such as self-care and treatment adherence, which have been associated with improved patient outcomes.17

Therefore, the objective of this scoping review was to investigate and analyze articles related to CLL patient and caregiver physical, psychological, social, and spiritual well-being published between January 1, 2015, and June 15, 2020. These articles will be used to provide an evidence base for the development of an integrative digital education platform to empower patients and their caregivers following a CLL diagnosis and throughout the continuum of care. These components were chosen based on a previous study evaluating how a family caregiver’s QOL is impacted by their role as a caregiver of a patient with lung cancer. A preliminary search for existing relevant scoping reviews was conducted using PubMed and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; no previous scoping review on this topic was identified.

Methods

Inclusion Criteria

This scoping review considered all studies and interventions, including quantitative studies, qualitative studies, and systematic reviews, implemented and evaluated in the context of physical, psychological, social, and spiritual well-being of patients diagnosed with CLL or their caregivers.

Search Strategy

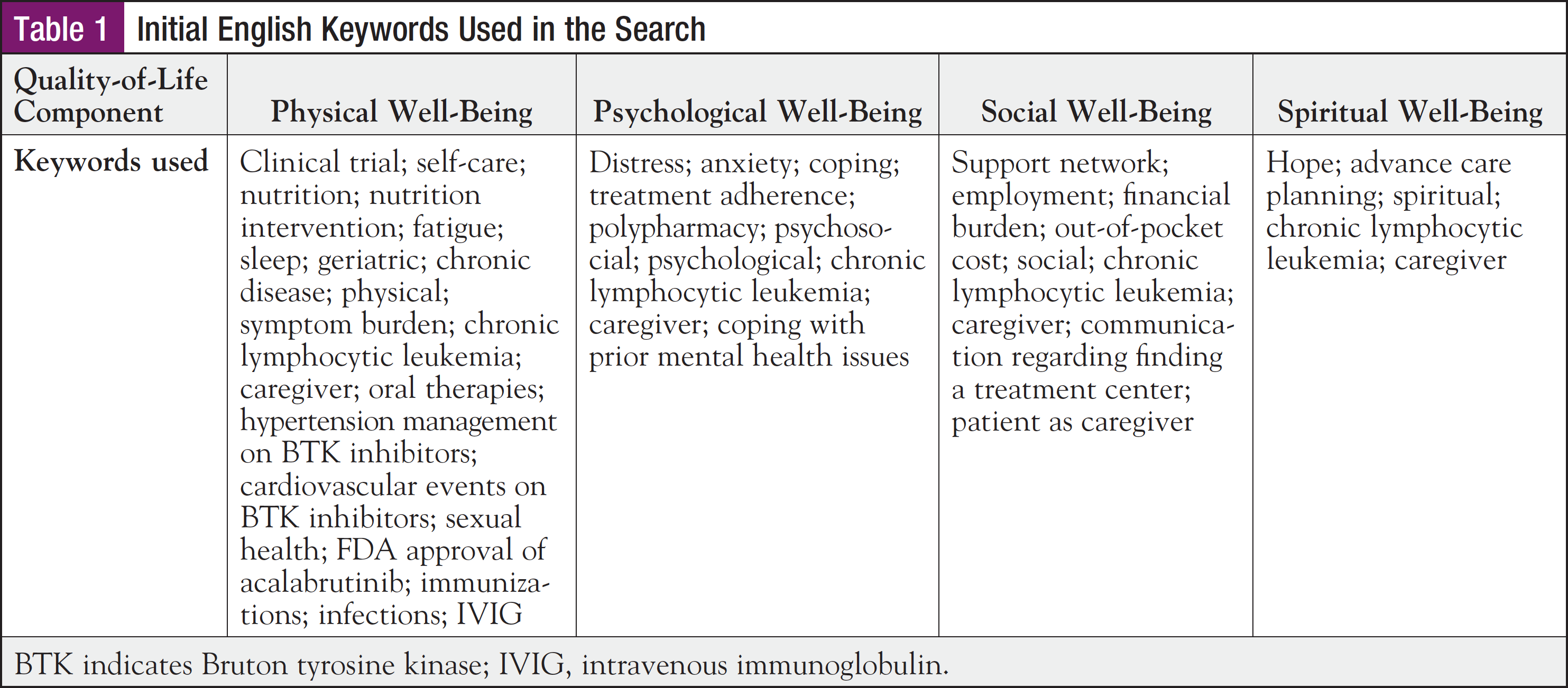

A 3-step search strategy was undertaken: (1) an initial limited search of PubMed; (2) an extensive search using all identified keywords and index terms; and (3) a hand search of the reference lists of included articles. This review was limited to studies published in English between January 1, 2015, and June 15, 2020. The search was conducted in the PubMed database. Keywords used in the search are shown in Table 1. The full search strategy, including all identified articles, is presented in the Appendix.

Identified articles were assessed for relevance to the current review based on information provided in the title and abstract by 2 independent reviewers. If the reviewers doubted the relevance of a study from the abstract, the full-text article was retrieved. Full-text articles were retrieved for all studies that met the inclusion criteria.

Two reviewers independently examined the full-text articles to determine whether they met inclusion criteria. Disagreements that arose between reviewers were resolved through discussion or input from a third reviewer. Studies identified from reference lists were assessed for relevance based on titles and abstracts.

Extraction of Results

Data were extracted from the included articles using a charting instrument aligned with this research objective and question. Study details and characteristics extracted included the following: author, year of publication, country of origin, study design, sample size and statistical methods, purpose/results/findings, limitations, and conclusions and implications. The QOL component was also identified. Data were extracted independently by 2 reviewers; any disagreements that arose were resolved through discussion or input from a third reviewer.

Results

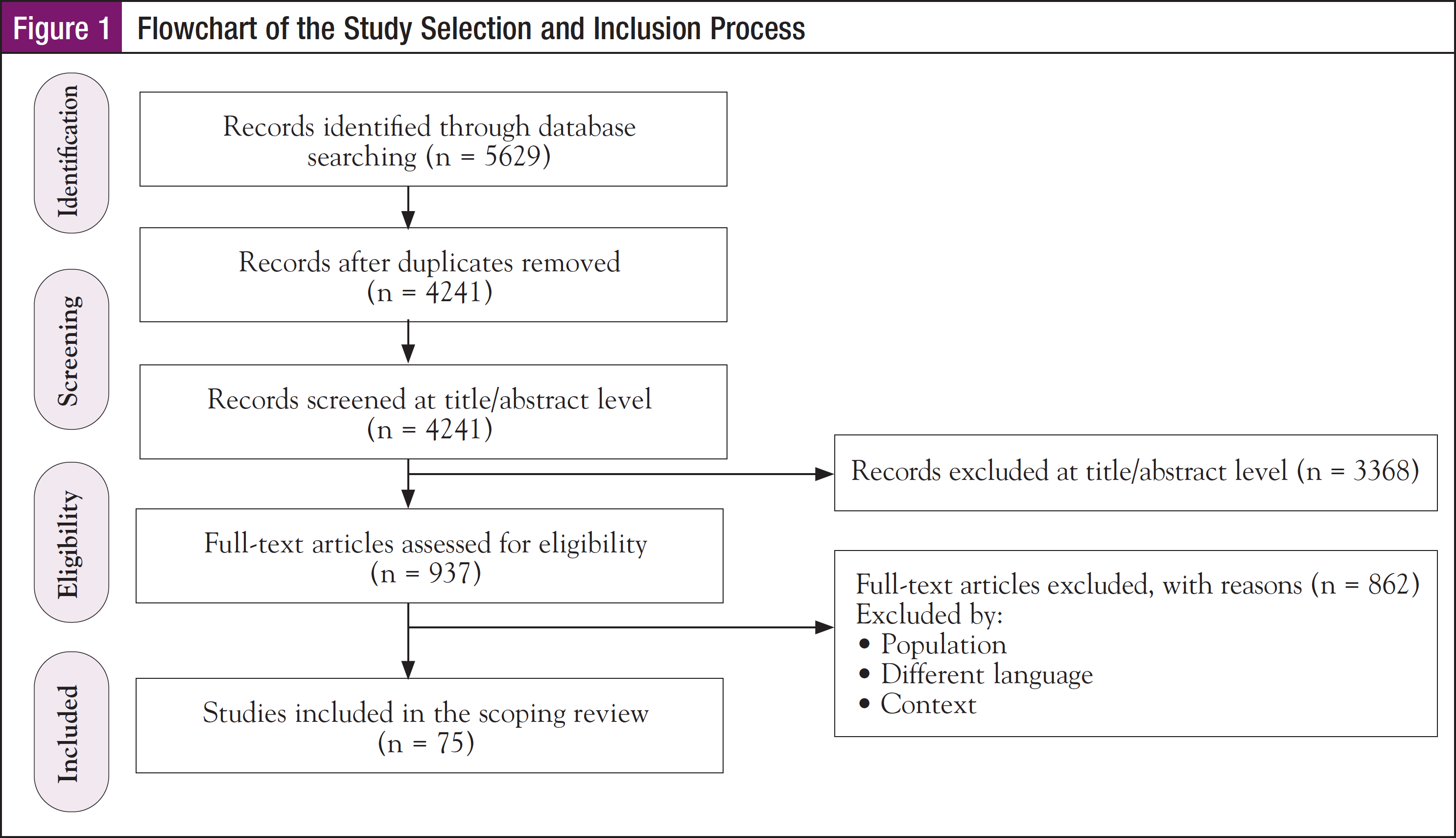

After removing duplicates, 4241 articles were screened for inclusion. A total of 937 articles met the inclusion criteria based on titles and abstracts, and full-text publications were then reviewed. After review of full-text publications, 75 relevant articles were identified. Figure 1 shows the study selection process.

Country of Publication

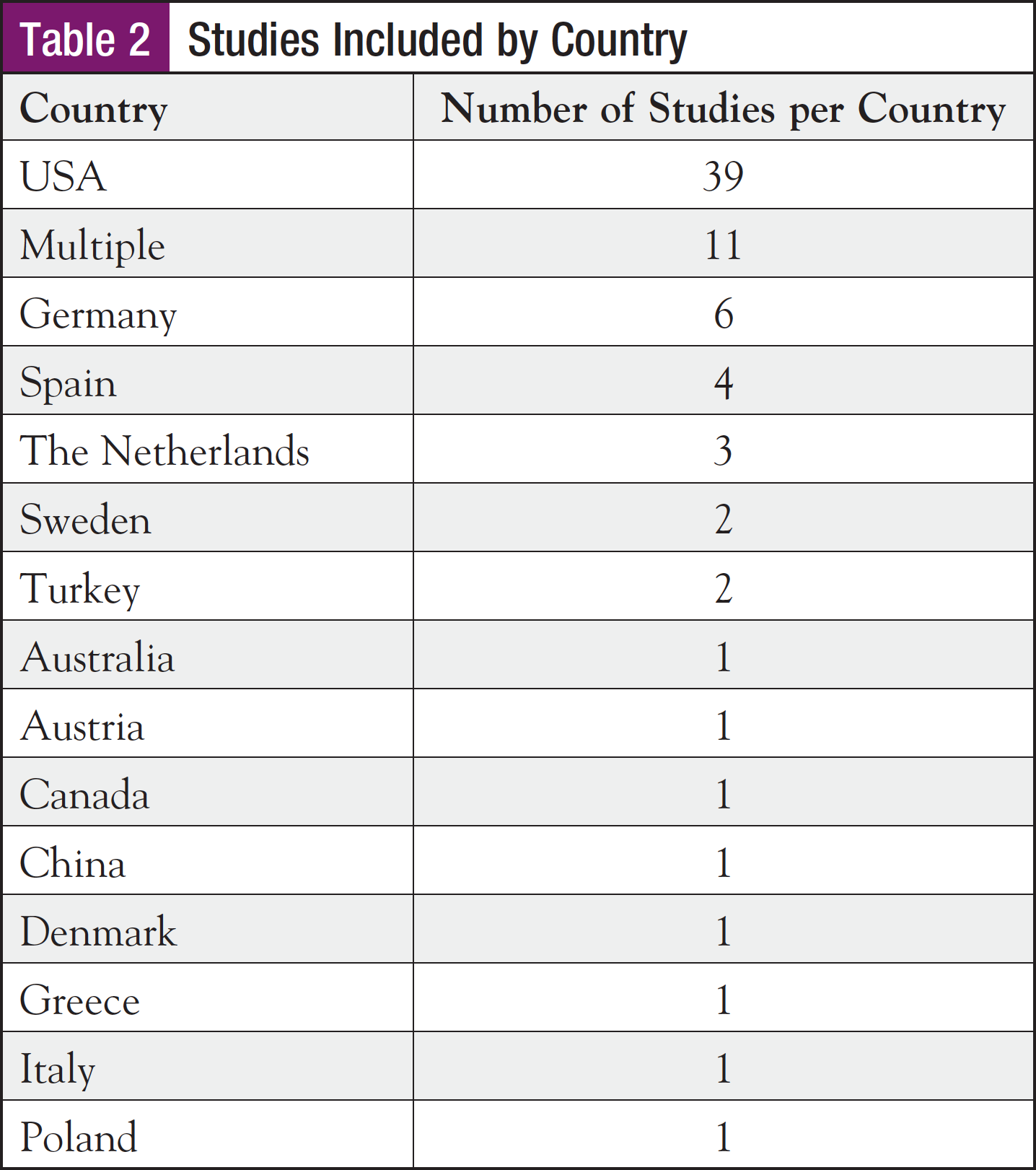

Most of the studies included in this scoping review were conducted in the United States, as shown in Table 2.

Research Design

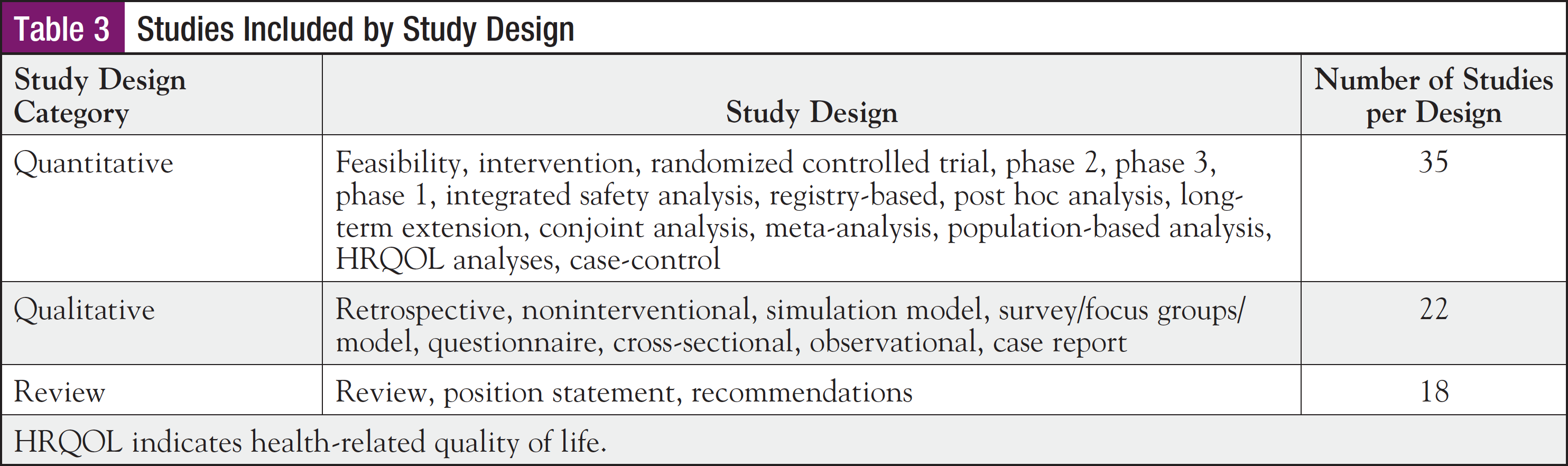

A total of 35 studies used a quantitative design, 22 a qualitative design, and 18 used review or systematic review methodology. Table 3 shows the studies included in this scoping review by study design.

Year of Publication

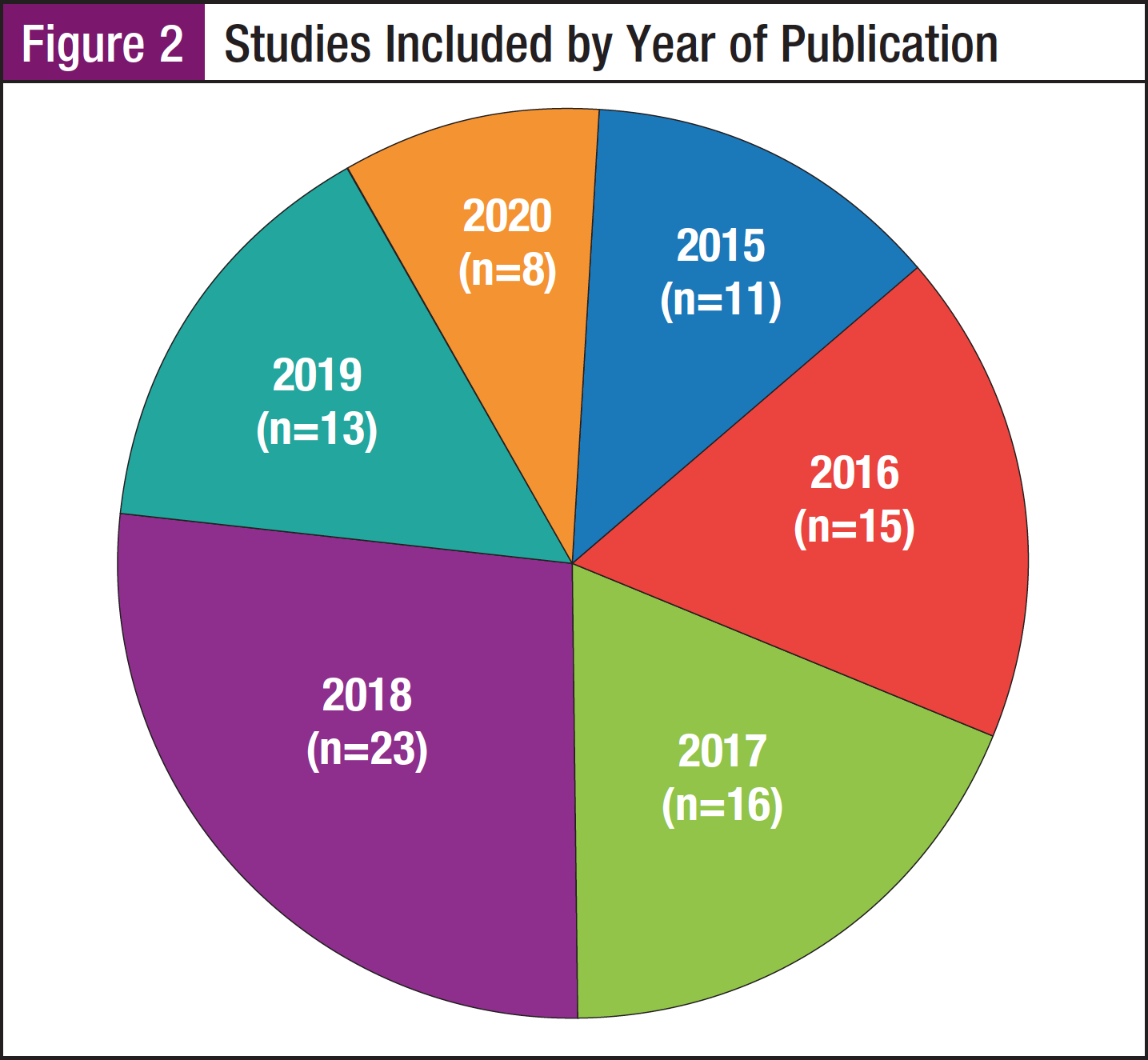

Included studies were published between January 1, 2015, and June 15, 2020. Figure 2 shows the year of publication of studies included in this scoping review. Figure 3 shows studies categorized by QOL domain and publication year.

Contexts and Populations of Studies

The majority of the analyzed studies were implemented in oncology settings or from population- or registry-based samples. Overall, no studies investigated the relationship between patients with CLL and their caregivers, and a single study was designed to assess caregiver health status.

Physical Well-Being

We identified 69 articles evaluating the physical domain for patients with CLL and their caregivers.18-86 Of these articles, 5 discussed nutrition, 5 discussed fatigue, 15 discussed geriatric considerations, 19 discussed treatment (eg, options, combinations, efficacy, adverse events), 1 discussed novel/oral therapies, 3 discussed infection/immunoglobulin replacement therapy, 1 discussed vaccinations, 3 discussed hypertension management following treatment with a Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor, 5 discussed cardiovascular events related to BTK inhibitors, 2 discussed sexual health, and 1 discussed FDA approval of acalabrutinib.

General topics covered in articles related to treatment include information about different available treatment options and combinations (eg, chemoimmunotherapy), preliminary treatment activity, and reported adverse events.21,22,25-29,33-35,38,41,46,49,56,61,67,68,70-86 Other articles discussed symptom burden and the effects of symptoms on health-related QOL.36,47,48,51,62 Some articles focused specifically on treatments in older patients, including treatment activity, outcomes, and tools for assessing health status.18-20,24,37,39,40,42,44,53,57,58,60,66,69 Other articles were designed to demonstrate the effects of vitamin D supplementation and other nutritional aspects that may have a role in the biology of CLL.23,32,50,63,65 Together, these articles highlight patients’ needs for education in the areas related to physical QOL, including treatment modalities, adverse event management, symptom burden and effects on health-related QOL, and nutritional interventions to impact CLL risk, with a particular focus on the subset of elderly patients.

Psychological Well-Being

We identified 13 articles evaluating the psychological domain.3,30,43,52,54,55,59,64,78,79,87-89 Overall, 9 articles spanned the psychological and physical components and 2 spanned the psychological and social components.

Several articles focused on the impact of psychological distress and social support on QOL and psychological functioning.43,55,59,87 Another group of articles focused on the effects of depression and anxiety on treatment and illness perceptions.3,30,52,54,64,88 Studies also investigated the importance of sexuality, sexual desire, sexual ability, and body image.78,79 A single article investigated health utility scores among family caregivers for patients with leukemia.89 Taken together, these articles demonstrate patients’ needs for support in areas related to the psychological QOL component, including the effects of cancer-related stress and symptoms on health-related QOL, and effects of a diagnosis on both patients and caregivers in terms of health-related QOL.

Social Well-Being

A total of 4 articles evaluated the social domain for patients with CLL and their caregivers.52,89-91 These articles evaluated support networks and financial components.

Oral targeted therapies are projected to improve survivorship among patients with CLL; however, they may impose a substantial financial burden.90 Sustainable pricing strategies for these therapies are needed to avoid financial toxicity for patients. Notably, providing information related to even small out-of-pocket costs leads patients to change their selection for hypothetical treatments, which suggests that patients are sensitive to cost.91 Qualitative data obtained through social media applications are potentially useful in supporting concept identification for new instruments designed to assess patient-reported outcomes.52 Family caregivers for patients with leukemia have lower health utility scores compared with the local general population, which highlights the importance of addressing the concerns of this population.89 These articles provide evidence for patients’ needs for education in these areas related to social QOL.

Spiritual Well-Being

Only 1 article was identified that evaluated the spiritual domain.31 This study demonstrated that the somatic, psychic, and spiritual end-of-life care following allogeneic stem cell transplantation could be optimized. The transplant team is challenged to realize the necessity of switching the curative concept into a palliative ambition. An intensification of cooperation is required between transplant and palliative care teams. These results support the consideration of spiritual well-being that may require a palliative versus curative approach for patients with CLL.

Discussion

The purpose of this scoping review was to investigate and analyze articles related to CLL patient and caregiver physical, psychological, social, and spiritual well-being published between January 1, 2015, and June 15, 2020. These articles will be used to provide an evidence base for the development of an integrative education tool to empower patients and their caregivers following CLL diagnosis and throughout the continuum of care.

To this end, 75 studies, including 18 reviews, were included. Most studies were published in 2017 and 2018. Each year from 2015 to 2018, 10 or more studies were published related to physical well-being, which was the most common QOL domain represented in the current scoping review.

Overall, these findings clearly highlight the needs of patients with CLL related to the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual QOL domains and the importance of including this information as part of a patient education tool that is provided to patients and their caregivers to be used at CLL diagnosis and throughout the continuum of care.

It is well established that a diagnosis of cancer contributes to significant burden, particularly related to QOL, on both the patient and the caregiver. However, in this scoping review, only 1 study focused on effects in caregivers; the remaining studies focused on QOL effects only in patients with CLL.

This scoping review further supported a paucity of information related to spiritual well-being, which limits the ability to include this QOL domain in a patient education tool.

Limitations of the Included Studies

The methodological quality of the studies included in the current scoping review was not assessed due to a lack of relevance for the current work; however, limitations are reported to provide information and guidance for future research or systematic reviews. Limitations include study designs prone to bias and small sample sizes.

These limitations could diminish the rigorous assessment of the impact of interventions related to QOL. Furthermore, they should be addressed while keeping in mind that a lack of scientific evidence supporting the effectiveness of the QOL interventions is a barrier to the implementation of an education tool for patients.

Limitations of the Scoping Review

There are limitations to the current scoping review. This scoping review was limited based on the exclusion of studies that were not published in English. Articles published in other languages could provide additional pertinent information. Another limitation is that only studies published between January 1, 2015, and June 15, 2020, were included. Older studies investigating the QOL domains may have provided additional relevant information for this review.

Because the aim of this scoping review was to examine studies related to CLL patient and caregiver physical, psychological, social, and spiritual QOL domains, no rating of methodological quality is provided; therefore, no recommendations for practice can be graded.

Conclusions

This scoping review was designed to evaluate studies related to CLL patient and caregiver physical, psychological, social, and spiritual well-being published between January 1, 2015, and June 15, 2020, to provide an evidence base for the development of an integrative education tool to empower patients and their caregivers following a CLL diagnosis and throughout the continuum of care.

A total of 75 relevant studies were identified. The most frequently evaluated QOL domain was focused on physical well-being. The studies were implemented mostly in oncology and population- and registry-based sample settings. The articles highlighted patients’ needs for information regarding physical (eg, symptoms, treatment, interventions), psychological (eg, depression and anxiety, effects of symptoms on QOL, caregiver QOL), social (eg, financial toxicity and support networks), and spiritual (eg, inclusion of content targeting spiritual needs in end-of-life care) QOL domains. Together, these findings provide an evidence base for the development of an integrative education tool to empower patients and their caregivers following a CLL diagnosis and throughout the continuum of care.

Implications for Research

Future primary research should focus on spiritual well-being in patients with CLL and their caregivers, and more studies should focus on the impact of a CLL diagnosis and treatment on caregivers. Importantly, studies should clearly identify study design, intervention characteristics, and context.

Although most of the studies focused on quantitative measures, additional research is needed to determine the effectiveness of interventions designed to assess specific QOL domains. Additionally, systematic reviews on patient/caregiver relationships, focusing on different QOL domains, and the spiritual, social, and psychological well-being of patients with CLL should be conducted to provide accurate and up-to-date evidence regarding the effects on QOL and to help inform clinical practice.

References

- American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. www.cancer.org/cancer/chronic-lymphocytic-leukemia/about/key-statistics.html. 2021.

- Cannella L, Caocci G, Jacobs M, et al. Health-related quality of life and symptom assessment in randomized controlled trials of patients with leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes: what have we learned? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2015;96:542-554.

- Robbertz AS, Weiss DM, Awan FT, et al. Identifying risk factors for depression and anxiety symptoms in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28:1799-1807.

- Scarfò L, Ferreri AJM, Ghia P. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016;104:169-182.

- Gribben JG. How I treat CLL up front. Blood. 2010;115:187-197.

- Northouse L, Williams AL, Given B, McCorkle R. Psychosocial care for family caregivers of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1227-1234.

- Blum K, Sherman DW. Understanding the experience of caregivers: a focus on transitions. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2010;26:243-258.

- Hudson P. Positive aspects and challenges associated with caring for a dying relative at home. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2004;10:58-65.

- Proot IM, Abu-Saad HH, ter Meulen RH, et al. The needs of terminally ill patients at home: directing one’s life, health and things related to beloved others. Palliat Med. 2004;18:53-61.

- Given B, Wyatt G, Given C, et al. Burden and depression among caregivers of patients with cancer at the end of life. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2004;31:1105-1117.

- Hodges LJ, Humphris GM, Macfarlane G. A meta-analytic investigation of the relationship between the psychological distress of cancer patients and their carers. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:1-12.

- Palos GR, Mendoza TR, Liao KP, et al. Caregiver symptom burden: the risk of caring for an underserved patient with advanced cancer. Cancer. 2011;117:1070-1079.

- Badr H, Taylor CL. Social constraints and spousal communication in lung cancer. Psychooncology. 2006;15:673-683.

- Hauser K, Koerfer A, Kuhr K, et al. Outcome-relevant effects of shared decision making. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112:665-671.

- Joosten EA, DeFuentes-Merillas L, de Weert GH, et al. Systematic review of the effects of shared decision-making on patient satisfaction, treatment adherence and health status. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77:219-226.

- Zimmerman E, Woolf SH. Understanding the Relationship Between Education and Health. Discussion Paper. Institute of Medicine, Washington, DC; 2014.

- Suarez-Almazor ME, Richardson M, Kroll TL, Sharf BF. A qualitative analysis of decision-making for total knee replacement in patients with osteoarthritis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2010;16:158-163.

- Abel GA, Klepin HD. Frailty and the management of hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2018;131:515-524.

- Al-Sawaf O, Bahlo J, Robrecht S, et al. Outcome of patients aged 80 years or older treated for chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2018;183:727-735.

- Balducci L, Dolan D. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the elderly: epidemiology and proposed patient-related approach. Cancer Control. 2015;22(4 Suppl):3-6.

- Barr PM, Robak T, Owen C, et al. Sustained efficacy and detailed clinical follow-up of first-line ibrutinib treatment in older patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: extended phase 3 results from RESONATE-2. Haematologica. 2018;103:1502-1510.

- Barrientos JC, O’Brien S, Brown JR, et al. Improvement in parameters of hematologic and immunologic function and patient well-being in the phase III RESONATE study of ibrutinib versus ofatumumab in patients with previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018;18:803-813.

- Bertrand KA, Giovannucci E, Rosner BA, et al. Dietary fat intake and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in 2 large prospective cohorts. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106:650-656.

- Bonanad S, De la Rubia J, Gironella M, et al. Development and psychometric validation of a brief comprehensive health status assessment scale in older patients with hematological malignancies: the GAH scale. J Geriatr Oncol. 2015;6:353-361.

- Brown JR, Davids MS, Rodon J, et al. Phase I trial of the Pan-PI3K inhibitor pilaralisib (SAR245408/XL147) in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) or relapsed/refractory lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:3160-3169.

- Brown JR, Hamadani M, Hayslip J, et al. Voxtalisib (XL765) in patients with relapsed or refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma or chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: an open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2018;5:e170-e180.

- Brumbaugh Paradis H, Alter D, Llerandi D. Venetoclax: management and care for patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2017;21:604-610.

- Burger JA, Tedeschi A, Barr PM, et al. Ibrutinib as initial therapy for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2425-2437.

- Burris HA 3rd, Flinn IW, Patel MR, et al. Umbralisib, a novel PI3Kδ and casein kinase-1ε inhibitor, in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and lymphoma: an open-label, phase 1, dose-escalation, first-in-human study. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:486-496.

- Burton CL, Galatzer-Levy IR, Bonanno GA. Treatment type and demographic characteristics as predictors for cancer adjustment: prospective trajectories of depressive symptoms in a population sample. Health Psychol. 2015;34:602-609.

- Busemann C, Jülich A, Buchhold B, et al. Clinical course and end-of-life care in patients who have died after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017;143:2067-2076.

- Casabonne D, Gracia E, Espinosa A, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and vitamin C transporter gene (SLC23A2) polymorphisms in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Eur J Nutr. 2017;56:1123-1133.

- Coutré SE, Furman RR, Flinn IW, et al. Extended treatment with single-agent ibrutinib at the 420 mg dose leads to durable responses in chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:1149-1155.

- Coutre S, Choi M, Furman RR, et al. Venetoclax for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia who progressed during or after idelalisib therapy. Blood. 2018;131:1704-1711.

- Coutre SE, Byrd JC, Hillmen P, et al. Long-term safety of single-agent ibrutinib in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia in 3 pivotal studies. Blood Adv. 2019;3:1799-1807.

- Cramer P, Fraser G, Santucci-Silva R, et al. Improvement of fatigue, physical functioning, and well-being among patients with severe impairment at baseline receiving ibrutinib in combination with bendamustine and rituximab for relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma in the HELIOS study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2018;59:2075-2084.

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, González B, de la Rubia J, et al. Further psychometric validation of the GAH scale: responsiveness and effect size. J Geriatr Oncol. 2017;8:211-215.

- Davids MS, Hallek M, Wierda W, et al. Comprehensive safety analysis of venetoclax monotherapy for patients with relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:4371-4379.

- Eichhorst B, Hallek M, Goede V. New treatment approaches in CLL: challenges and opportunities in the elderly. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7:375-382.

- Eichhorst B, Hallek M, Goede V. Management of unfit elderly patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Eur J Intern Med. 2018;58:7-13.

- Flinn IW, Cherry MA, Maris MB, et al. Combination trial of duvelisib (IPI-145) with rituximab or bendamustine/rituximab in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma or chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Am J Hematol. 2019;94:1325-1334.

- Goede V, Bahlo J, Chataline V, et al. Evaluation of geriatric assessment in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results of the CLL9 trial of the German CLL study group. Leuk Lymphoma. 2016;57:789-796.

- Goyal NG, Maddocks KJ, Johnson AJ, et al. Cancer-specific stress and trajectories of psychological and physical functioning in patients with relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Ann Behav Med. 2018;52:287-298.

- Heraly B, Morrison VA. How I treat chronic lymphocytic leukemia in older patients. J Geriatr Oncol. 2015;6:333-340.

- Hillmen P, Janssens A, Babu KG, et al. Health-related quality of life and patient-reported outcomes of ofatumumab plus chlorambucil versus chlorambucil monotherapy in the COMPLEMENT 1 trial of patients with previously untreated CLL. Acta Oncol. 2016;55:1115-1120.

- Holkova B, Yazbeck V, Kmieciak M, et al. A phase 1 study of bortezomib and romidepsin in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, indolent B-cell lymphoma, peripheral T-cell lymphoma, or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58:1349-1357.

- Holtzer-Goor KM, Schaafsma MR, Joosten P, et al. Quality of life of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia in the Netherlands: results of a longitudinal multicentre study. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:2895-2906.

- Jain P, Keating M, Renner S, et al. Ruxolitinib for symptom control in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a single-group, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4:e67-e74.

- Kempin S, Sun Z, Kay NE, et al. Pentostatin, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab followed by alemtuzumab for relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a phase 2 trial of the ECOG-Acrin Cancer Research Group (E2903). Acta Haematol. 2019;142:224-232.

- Kubeczko M, Novara E, Spychałowicz W, et al. Efficacy and safety of vitamin D supplementation in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online). 2016;70:534-541.

- Landfeldt E, Eriksson J, Ireland S, et al. Patient, physician, and general population preferences for treatment characteristics in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a conjoint analysis. Leuk Res. 2016;40:17-23.

- McCarrier KP, Bull S, Fleming S, et al. Concept elicitation within patient-powered research networks: a feasibility study in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Value Health. 2016;19:42-52.

- Molica S, Giannarelli D, Levato L, et al. A simple score based on geriatric assessment predicts survival in elderly newly diagnosed chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients. Leuk Lymphoma. 2019;60:845-847.

- Montillo M, Illés Á, Robak T, et al. Idelalisib addition has neutral to beneficial effects on quality of life in bendamustine/rituximab-treated patients: results of a phase 3, randomized, controlled trial. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17:173.

- Morrison EJ, Flynn JM, Jones J, et al. Individual differences in physical symptom burden and psychological responses in individuals with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Ann Hematol. 2016;95:1989-1997.

- Nastoupil LJ, Lunning MA, Vose JM, et al. Tolerability and activity of ublituximab, umbralisib, and ibrutinib in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a phase 1 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet Haematol. 2019;6:e100-e109.

- O’Brien SM, Lamanna N, Kipps TJ, et al. A phase 2 study of idelalisib plus rituximab in treatment-naïve older patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2015;126:2686-2694.

- Ocias LF, Larsen TS, Vestergaard H, et al. Trends in hematological cancer in the elderly in Denmark, 1980-2012. Acta Oncol. 2016;55(suppl 1):98-107.

- Papathanasiou IV, Kelepouris K, Valari C, et al. Depression, anxiety and stress among patients with hematological malignancies and the association with quality of life: a cross-sectional study. Med Pharm Rep. 2020;93:62-68.

- Rowswell-Turner RB, Barr PM. Treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia in older adults. J Geriatr Oncol. 2017;8:315-319.

- Sawas A, Farber CM, Schreeder MT, et al. A phase 1/2 trial of ublituximab, a novel anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, in patients with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma or chronic lymphocytic leukaemia previously exposed to rituximab. Br J Haematol. 2017;177:243-253.

- Schoormans D, Husson O, Oerlemans S, et al. Having co-morbid cardiovascular disease at time of cancer diagnosis: already one step behind when it comes to HRQoL? Acta Oncol. 2019;58:1684-1691.

- Sfeir JG, Drake MT, LaPlant BR, et al. Validation of a vitamin D replacement strategy in vitamin D-insufficient patients with lymphoma or chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood Cancer J. 2017;7:e526.

- Shreders AJ, Niazi SK, Hodge DO, et al. Correlation of sociodemographic and clinical parameters with depression and distress in patients with hematologic malignancies. Ann Hematol. 2018;97:519-528.

- Solans M, Castelló A, Benavente Y, et al. Adherence to the Western, Prudent, and Mediterranean dietary patterns and chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the MCC-Spain study. Haematologica. 2018;103:1881-1888.

- Stauder R, Eichhorst B, Hamaker ME, et al. Management of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) in the elderly: a position paper from an international Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) Task Force. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:218-227.

- Strati P, Lanasa M, Call TG, et al. Ofatumumab monotherapy as a consolidation strategy in patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2016;3:e407-e414.

- von Tresckow J, Eichhorst B, Bahlo J, Hallek M. The treatment of chronic lymphatic leukemia. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2019;116:41-46.

- Woyach JA. What is the optimal management of older CLL patients? Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2018;31:83-89.

- Younes A, Broody J, Carpio C, et al. Safety and activity of ibrutinib in combination with nivolumab in patients with relapsed non-Hodgkin lymphoma or chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a phase 1/2a study. Lancet Haematol. 2019;6:e67-e78.

- Brown JR. How I treat CLL patients with ibrutinib. Blood. 2018;131: 379-386.

- Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, et al. Ibrutinib treatment for first-line and relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: final analysis of the pivotal phase Ib/II PCYC-1102 study. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:3918-3927.

- Gribben JG, Bosch F, Cymbalista F, et al. Optimising outcomes for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia on ibrutinib therapy: European recommendations for clinical practice. Br J Haematol. 2018;180:666-679.

- Gülsaran SK, Baysal M, Demirci U, et al. Late onset left ventricular dysfunction and cardiomyopathy induced with ibrutinib. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2020;26:478-480.

- Kim MS, Prasad V. US Food and Drug Administration approvals for Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: potential inefficiencies in trial design and evidence generation. Cancer. 2020;126:4270-4272.

- Lachance S, Christofides AL, Lee JK, et al. A Canadian perspective on the use of immunoglobulin therapy to reduce infectious complications in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Curr Oncol. 2016;23:42-51.

- Na IK, Buckland M, Agostini C, et al. Current clinical practice and challenges in the management of secondary immunodeficiency in hematological malignancies. Eur J Haematol. 2019;102:447-456.

- Olsson C, Sandin-Bojö AK, Bjuresäter K, Larsson M. Changes in sexuality, body image and health related quality of life in patients treated for hematologic malignancies: a longitudinal study. Sex Disabil. 2016;34:367-388.

- Olsson C, Sandin-Bojö AK, Bjuresäter K, Larsson M. Patients treated for hematologic malignancies: affected sexuality and health-related quality of life. Cancer Nurs. 2015;38:99-110.

- Paydas S. Management of adverse effects/toxicity of ibrutinib. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2019;136:56-63.

- Roeker LE, Sarraf Yazdy M, Rhodes J, et al. Hypertension in patients treated with ibrutinib for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1916326.

- Sánchez-Ramón S, Dhalla F, Chapel H. Challenges in the role of gammaglobulin replacement therapy and vaccination strategies for hematological malignancy. Front Immunol. 2016;7:317.

- Sharman JP, Egyed M, Jurczak W, et al. Acalabrutinib with or without obinutuzumab versus chlorambucil and obinutuzmab for treatment-naive chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (ELEVATE TN): a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;395:1278-1291.

- Stühlinger MC, Weltermann A, Staber P, et al. Recommendations for ibrutinib treatment in patients with atrial fibrillation and/or elevated cardiovascular risk. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2020;132:97-109.

- Tang CPS, McMullen J, Tam C. Cardiac side effects of bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors. Leuk Lymphoma. 2018;59:1554-1564.

- Waldron M, Winter A, Hill BT. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic considerations in the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: ibrutinib, idelalisib, and venetoclax. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2017;56:1255-1266.

- Arts LPJ, Oerlemans S, Tick L, et al. More frequent use of health care services among distressed compared with nondistressed survivors of lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results from the population-based PROFILES registry. Cancer. 2018;124:3016-3024.

- Westbrook TD, Maddocks K, Andersen BL. The relation of illness perceptions to stress, depression, and fatigue in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Psychol Health. 2016;31:891-902.

- Yu H, Zhang H, Yang J, et al. Health utility scores of family caregivers for leukemia patients measured by EQ-5D-3L: a cross-sectional survey in China. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:950.

- Chen Q, Jain N, Ayer T, et al. Economic burden of chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the era of oral targeted therapies in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:166-174.

- Mansfield C, Masaquel A, Sutphin J, et al. Patients’ priorities in selecting chronic lymphocytic leukemia treatments. Blood Adv. 2017;1:2176-2185.

Appendix. Search Strategy